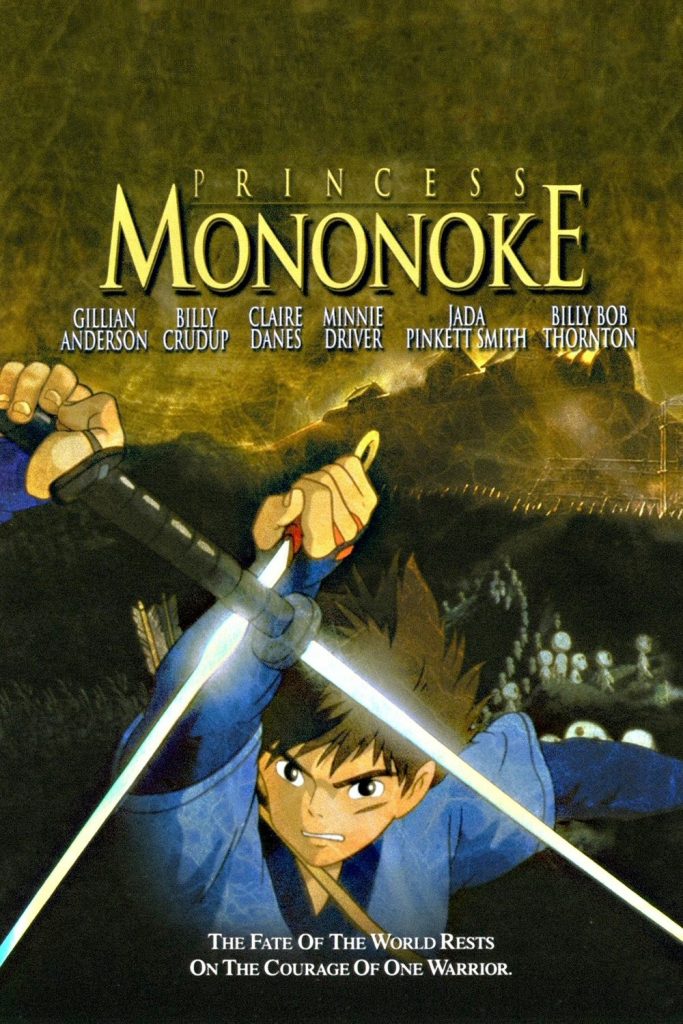

Princess Mononoke (Mononoke-hime) is a Studio Ghibli film, written and directed by co-founder Hayao Miyazaki in 1997. The film takes place in the Muromachi period of Ancient Japan and follows protagonist Ashitaka on his journey to locate the origins of the demon beasts. In this world, Miyazaki has chosen to depict animals, not only in a natural sense as living in nature, but also as a vessel for gods. A Boar God, which is possessed and demonic, attacks Ashitaka’s village, Emishi, in the beginning of the film, and although Ashitaka is able to slay the beast, the beast injures his arm and he is banished by his village. Ashitaka must strive to find the source of the demon beast if he hopes to return home. During his journey, he encounters San, the wolf girl, and with her, he gets caught up in the battle between the human mercenaries and the spirit-animals for the land. Through the many perspectives and the fast paced changing plot, Miyazaki demonstrates a human and animal dynamic, not only depicting elements of anthropomorphism but also a return to the primitive and savagery.

The film encompasses a wide range of genres, which all speak to the center aspect of the film: the land in which the humans and animals are engaging. It is typical of Miyazaki to often hybridize multiple genres within his films to offer perspectives. Miyazaki incorporates the genre of stories based on Asian tradition because the film takes place in the Ancient Japan Muromachi period and fuses this with tales of the supernatural to account for the mononoke aspect of the film. The term mononoke refers to supernatural creatures often used in Japanese folklore. Miyazaki carefully crafts concepts and setting that are in line with the period in which he is situating his story, therefore also making the film a historical drama.

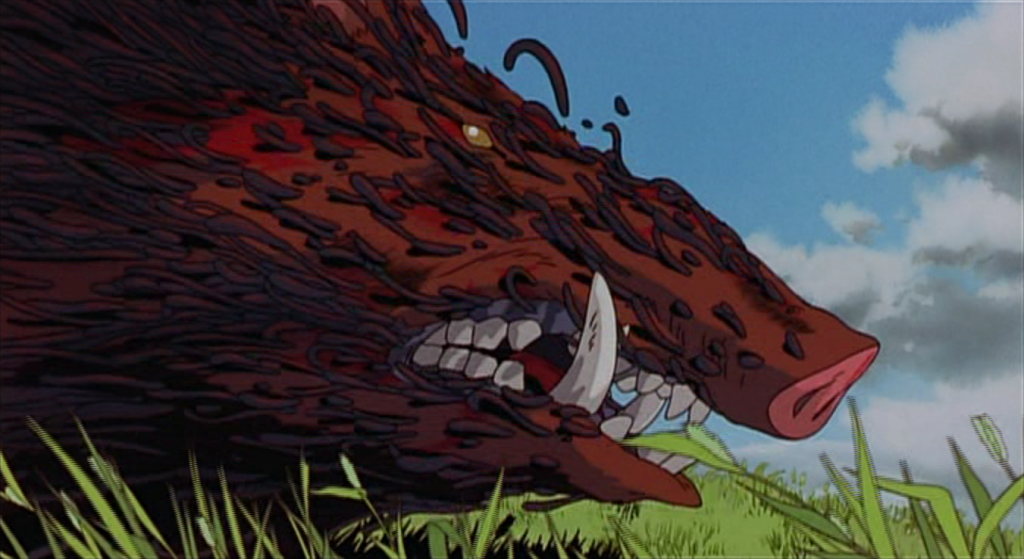

Other genres incorporated within the film include action, adventure and horror because of the journey protagonist Ashitaka has to go through and the many different animal gods, which he encounters. Although the film is animated, the horror aspect of the film is still present, especially in the transformation scenes of the boar gods being possessed by the demons (See Figure 1). The film also does not omit any of the violence or death scenes, which are typically shown off-screen in most animated features, including Japanese. Miyazaki subverts the audience’s expectations by showing scenes, (which appear to be more gruesome, in fact, turn out to be a display of affection. For example, in the beginning of the film, San, the wolf girl, is shown to be bloody, but in fact, she is trying to remove the bullet from her wolf mom’s body by using her mouth (See Figure 2). The image of San alone depicts savagery on first glance but in fact, is a depiction of love.

Figure 1

Figure 2

At the center of most Miyazaki films, the main genre is a love story. The love that is depicted is love for the land, which creates the dilemma between the animal gods and the humans. The animal gods love and want to preserve the land and the humans claim to love the land, but only for its resources. Love of family is also depicted, and San, the wolf girl, finds that in Moro, her wolf mom and her wolf siblings. Lastly, there is love between Ashitaka and San, but it is not the typical love story. Nathalie Op De Beeck makes an interesting remark regarding the two in stating, “Female and male warriors here are evenly matched in intellect, force of emotion, physical stamina and courage” (268). This demonstrates that the relationship that occurs here is not the typical story of a damsel in distress, but rather, Ashitaka actually embraces San, regardless of her choice of being with the wolf-clan. Ultimately, through the politics of human and animal relations in the film, the struggle is over the land and all the genres can speak to this in some way. Miyazaki has said himself that, “I’ve come to the point where I just can’t make a movie without addressing the problem of humanity as part of an ecosystem” (Thomas 85).

The animal presences in the film come in the form of animal gods and the viewer is first introduced to Nago, the demon possessed boar god. When an animal god is possessed, it is no longer itself and is inhabited by a dark spirit, and in the case of Ashitaka, this possession is also applicable and possible in the case of humans. The film also depicts boar gods that are non-possessed, and the viewer meets Okkoto, who is the blind boar god. The other animal god that is depicted: is the Wolf-Clan, which includes Wolf Goddess Moro and her children. Moro has taken in San and raised her as her own. Anthropomorphism is a significant factor in the creation of the animal god characters, and creates a type of hierarchy within the animal system, because there are clans, leaders and structure. There is also the great forest spirit in the film, which comes to in the form of a Deer, which many of the humans fight over because it is a symbol of immortality (See Figure 3).

Figure 3

Besides having animal gods depict human characteristics, there are human characters that depict quite animalistic characteristics. Ashitaka encounters a man named Jigo along his journey, whom he first believes to be a friend, but later learns that Jigo and his men disguised themselves as boars using boar skins to kill the forest spirit. It is later depicted that Jigo is doing this solely out of duty for the emperor. This demonstrates that the human characters had to disguise as animal characters to achieve what they needed. Another character, Lady Eboshi, is cruel and destroys the forest and all animals, but the viewer is shown Eboshi’s side of the story, and learns that she is destroying the forest for its resources for her people. Miyazaki refuses to give the viewer an explicit moral and therefore, no one is exactly punished at the end of the film, because it is demonstrated that there is a cause for someone’s actions, even if it is incorrect.

A lot of criticism comes to the film because of the lack of resolution. Even though the battle between the humans and animals ends, it is not really over and the end of the battle appears to only be temporary. Paul Wells makes a wonderful summative point about the film in his text, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, “Fundamentally, though, this is a narrative about the realization that regeneration may not be possible; the eco-system they represent and use is not an endless resource and speaks more to loss and crisis than to hope and continuity” (201). Miyazaki does not offer resolution to all the issues, and offers only temporary fixes so to speak, because ultimately, it is up to the viewer to decide. He refuses to oversimplify the issues and give a conclusion, because the film is modern, in the sense that it speaks to problems of the eco-system still evident today, regarding humans and animals. He analyzes the relationship between the humans-animal relations in an ecological context. Miyazaki portrays both sides of each character, human and animal, and there is no character beyond redemption (See Figure 4). He also depicts the effects of “industrialization”, especially in the world of Lady Eboshi and the problems of new machinery for wildlife and animals. Miyazaki carefully crafts a film that speaks about the problems of trying to put the human and animal world together, and ultimately perhaps gestures to the point that the two worlds cannot come together in peace.

Figure 4

Princess Mononoke is comparable to other Miyazaki films, that employ the use of anthropomorphism to speak to serious issues, My Neighbor Totoro (1988), where protagonists Satsuki and Mei, encounter a great forest spirit, Totoro, who help them cope with their mother being sick and moving away to a new place. They are able to understand the situation with their mother also learn the significance of friendship in sisterhood, with the help of their new friend Totoro. Miyazaki uses the fantasy element of introducing speaking animal gods, to perhaps make it easier for younger audiences to connect to the film and bridge the gap for deeper concepts.

Bibliography

Op De Beeck, Nathalie. “Anima and Anime: Environmental Perspectives and New Frontiers in Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away.” The Japanification of Children’s Popular Culture: From Godzilla to Miyazaki. Ed. Mark I. West.Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 2009. 267–284. Print.

Thomas, Jolyon Baraka. “Shukyo Asobi and Miyazaki Hayao’s Anime.” University of California Press 10.3 (2007): 73–95. Print. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions.

Wells, Paul. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Cultures. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009. Print.

Filmography

Princess Mononoke. Dir. Hayao Miyazaki. Studio Ghibli. 1997.

Further Reading References

Cavallaro, Dani. The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2006. Print.

Levi, Antonia. “The Werewolf in the Crested Kimono: The Wolf-Human Dynamic in Anime and Manga.” University of Minnesota Press 1. Emerging Worlds of Anime and Manga (2006): 144–160. Print.

McCarthy, Helen. Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation – Films, Themes, Artistry. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2002. Print.