Porco Rosso follows a former fighter pilot who abandoned the Italian military, transformed into a pig, and becomes a bounty hunter that fights pirates. One day he meets American pilot Curtis who was contracted by pirates and is in love with Porco’s friend Gina. Curtis realises Gina loves Porco despite him being a pig and tensions lead them into a dog fight in which Porco is shot down. Porco fixes his plane in Milan where he meets Fio who leaves with him. While at Porco’s hideout Fio wakes and sees his human form and asks how he became a pig and Porco responds “all middle-aged men are pigs,” but never explicitly states the cause. After a run in with the pirate gang Porco fights Curtis again but Gina warns the Italian air force are on their way. The group disperses but before leaving Fio kisses Porco. As he turns away with Curtis to create a diversion, Curtis calls “hey your face wait, wait up, turn around” implying that Porco has returned to his human form, but the viewer never sees this, leaving the ending ambiguous.

The film is an animated adventure comedy with some elements open to interpretation. Much of the humour comes from references to Porco’s pig like nature with offhand comments like “you really are a pig.” However, while this is used for comedic purposes, Porco’s stubborn traits and his transformation into a pig hint at darker subject issues around depression, disillusionment from humanity and self-image after fighting a war. Animation as a medium gave Hayao Miyazaki more creative freedoms to play around with these ideas while still maintaining a level of comedy. When watching animated films, the audience knows they are watching a fairy tale and not a factual documentary allowing for a greater suspension of disbelief around animal behaviour.[i] Therefore while Porco has the appearance of a pig, his retention of human characteristics blurs the line between humans and animals without cutting off the audience’s immersion.

In an interview with Animerica Miyazaki said, “Pigs are creatures which might be loved, but they are never respected. They’re synonymous with greed, obesity, debauchery. The word “pig” itself is used as an insult.”[ii] The use of pig related insults presents these ideas throughout the film, particularly from the pirates who call Porco a “stupid pig.” Animation as a medium allows for these insults to be challenged in a comedic way, as despite them calling him ‘stupid’ they are the ones who are defeated and therefore outsmarted and outmatched. Furthermore, pigs are social creatures and very intelligent.[iii] The use of stereotypical pig insults towards Porco shows that they only know him on a surface level rather than having a deeper understanding of his character showing how his pig exterior keeps him as an outsider. When comparing the behaviour of the pirates and the news reporters with Porco, Porco is more refined and less stereotypically pig like. The pirates and news reporters talk over Gina’s singing causing Curtis to become agitated and say, “shut up and listen to the song.” Porco also makes a joke that the pirates don’t “know how to bathe” to which they grow agitated until Gina comes to calm them down and reminds them not to fight in the restaurant. Meanwhile Porco is sat well-mannered and smoking which subverts expectations between animals and humans as it is the pirates that need taming.

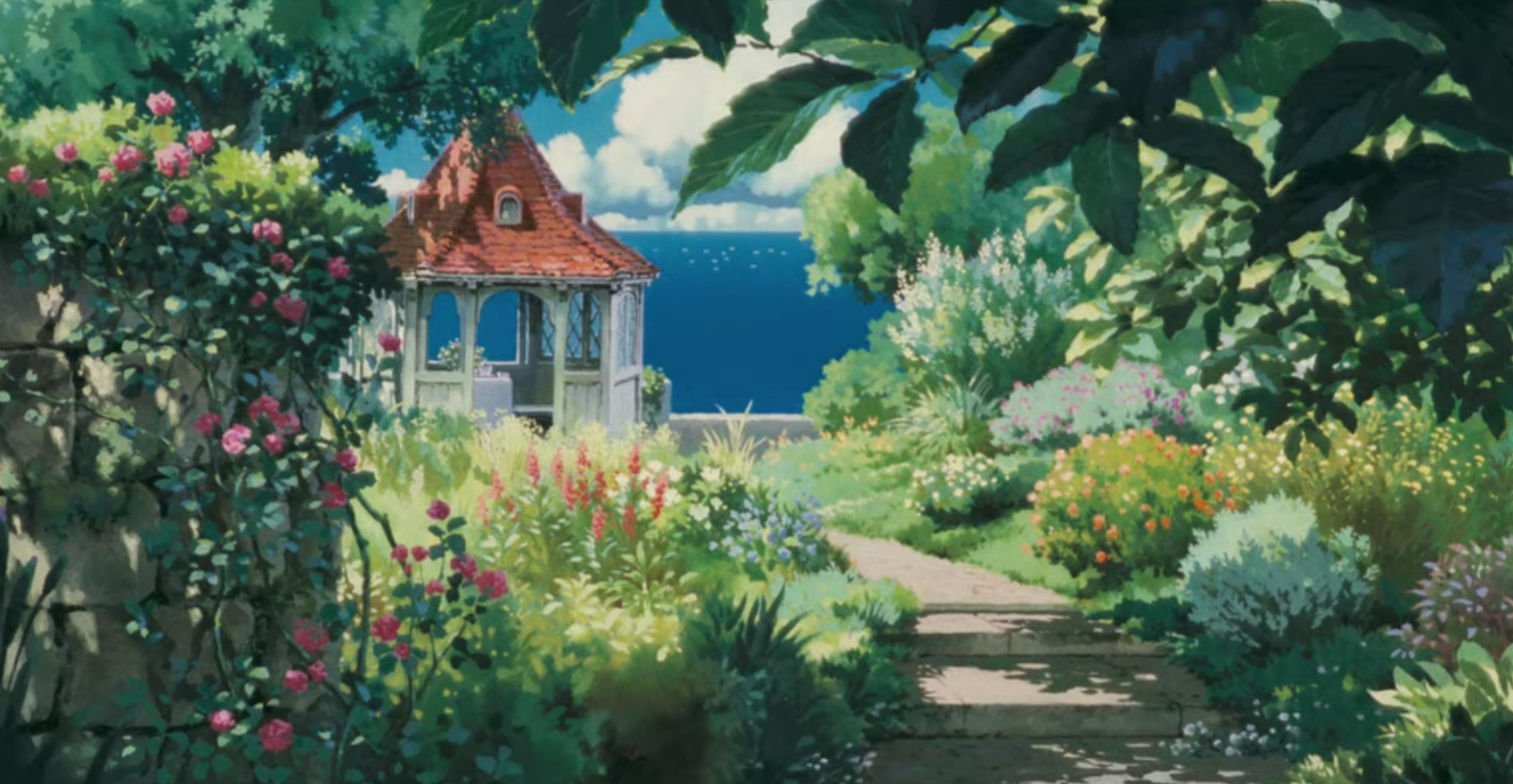

(Image 2- Gina telling the pirates off for getting rowdy)

While animated films have greater freedom in how they portray animals there are many occasions of human emotions being projected onto animals as a vehicle of expression.[iv] While it could be said that Porco Rosso also does this for comedic effect it also plays around with this idea as there are hints that Porco is performing to meet the stereotypes of pigs. When thinking about how humans interact with animals, their levels of attachment often reflect how they view them. Typically, cute animals such as dogs and cats have a higher status because of this, whereas animals that typically live outside such as pigs have less personal relationships with humans making it easier to detach from them. Porco seems to have no qualms with the pig jokes directed at him and even makes them himself saying “I’m a pig I don’t fight for honour.” Therefore, Porco himself seems to conform to stereotypes of pigs and shows awareness of such tropes in his own self depreciating humour. Yet while pigs are social creatures Porco keeps people at a distance showing how despite physically transforming into a pig his personality and characteristics are his own.

This is interesting when considering Porco’s transformation as it is never explicitly stated why he turned into a pig, but it seems to be a self-inflicted curse. Porco expresses occasional hints at being dissatisfied with his existence, but this seems to be aimed at life in general rather than being a pig. After Fio sees Porco briefly in his human form she asked him how he became a pig to which he replies, “all middle-aged men are pigs.” He then describes the “worst dog fight of my life” that killed his friend Bellini and the other members of his squad, and that during the fight he “thought only of himself and escaping.” This flashback shows the conflicting emotions he felt as he calls out to his friend “What about Gina? You can’t leave her alone let me go instead.” By juxtaposing this flashback with Porco’s description of middle-aged men, it is impossible not to draw a connection between the guilt Porco feels for fighting to live and his current pig like form. The insult ‘selfish pig’ will be familiar to many but the desire to live is instinctual to all life and not shameful. However, Porco becoming a pig shows that he see’s his survival as shameful and selfish to the extent that he discarded his humanity to cope with the trauma.

Therefore, it is more important to consider why Miyazaki presented Porco as a pig in this way. During the conversation with Fio Porco goes onto say “the good guys were the ones who died or maybe I’m dead and life as a pig is the same thing as hell.” The fact Porco is delivering this line shows he is clearly alive, so is likely referring to the death of his former self. Earlier in the film Gina refers to a photograph that is the “only picture left” of Porco as “a human” however Porco scratched his own face out. This could be interpreted as him being ashamed of his pig-self, but his behaviour implies that he is ashamed of his human self to the extent he can’t look at it. While talking to Fio at the hideout he says that “seeing you makes me wish I’d never given up being human.” This line is delivered with a full body shot of Porco emphasising his pig appearance but the use of ‘given up’ implies that humanity is something that Porco discarded. Furthermore, when Fio sees him in his human form she calls out to him by his former name “Marco,” but when he becomes aware that he is being watched he reverts to his pig appearance. This implies that not only does he perform stereotypical aspects of pigs, but that his pig appearance is connected to his own will, or at least his self-image, as a mechanism to further distance himself from humanity.

Despite keeping people at a distance Gina and Ferrarin call him “Marco” which was the name he used before being a pig. This shows a greater attachment to Porco the human, likely because they knew him before the war and can see through his performance. Yet despite others clearly caring about him, Porco is unaware of his value and that either Fio or Gina have feelings for him. When Curtis accuses him of “hogging all the women to himself,” Porco turns red in response emphasising his obliviousness. The term ‘male chauvinist pig’ has been used to describe men who oppose women’s liberation and are sexist.[v] On the surface Porco conforms to this, being hesitant to let Fio fix his plane because she is a woman. He also makes jokes about Fio’s “butt that’s bigger than it looks.” However, he eventually praises Fio’s engineering skills and rejects her offer to try and turn him back into a human with a kiss saying, “save it for somebody special,” showing that he respects her. Therefore, while he may have some sexist biases, these are exaggerated to fit his piggish persona and he is not as stubborn with his ways as he would have people believe. Furthermore, it shows that he does not see himself as ‘somebody special’ and therefore undeserving of love causing him to keep both Fio and Gina at a distance.

The ending of the film furthers this as Porco creates a diversion from the Italian air force so the others can escape. Porco forces Fio to leave with Gina despite her not wanting to and Gina says, “You always do this Marco it’s just not fair.” This action could be considered heroic as he is protecting Fio from a dangerous situation, however it is to further his stubborn pig façade. Gina’s tired tone shows that this gesture is not appreciated but her compliance implies awareness that she cannot change Porco’s mind. Therefore, while the background music creates a romantic and dramatic tone fitting for an adventure comedy, Porco’s rejection of Fio was ultimately selfish rather than a heroic deed showing deeper meaning beyond the surface genre. Despite being rejected Fio kisses Porco as she departs, and it is implied this turns him back into a human. It is unclear if this is permanent, but it is possible that this gesture of love and Fio’s persistence reconnected Porco to his human self by showing him he deserves to be loved.

The final scene also leaves the status of Porco ambiguous as it ends with Fio’s narration saying, “as for how Gina’s bet turned out, well that’s our secret.” A shot is shown of the empty garden where Gina waited for Porco but it is never stated if he ever came back for her. This could imply they left together or that she realised he would never change and stopped waiting. However earlier in the film Gina said “love is a little bit more complicated here than it is in America” showing that she loves Porco regardless of his nature and appearance and would wait for him forever. In reality loving a pig is taboo, however the animation genre and Porco’s anthropomorphic traits makes it possible to suspend our expectations of human and animal relations and root for the romance. The endings ambiguity conforms to the complexities of Porco’s transformation as his depression and pig form are intertwined, making a believable complete resolution unrealistic. However, Gina’s accepting love allows for hope even with the loose ends.

Therefore, throughout the film Porco, while a pig in appearance, performs the stereotypes of pigs rather than becoming a pig by nature. Pigs are intelligent and social animals, yet Porco keeps himself at a distance and gets called a “stupid pig” despite constantly outsmarting the pirates. Pigs are also outside animals and Porco keeps himself as an outsider from humanity showing how his transformation into a pig is something he has inflicted on himself to present his own self-image.

The origins of Porco’s trauma stem from fighting in war and survivors guilt causing him to become disillusioned from humanity. If his transformation into a pig is to keep people at a distance it could be implying that pigs are unlovable, however even after transforming there are people in the film such as Gina who care about him deeply. Porco’s speech and actions are recognisably human and while in many animated films this is a projection of humanness onto animals, Porco is projecting pig stereotypes onto himself. This also makes Porco Rosso interesting to compare with Miyazaki’s other film Spirited Away. Both films involve curses that turn a human into a pig, but In Spirited Away the pigs are not anthropomorphic and the curse is not self-inflicted leading to a very differentdepiction of pigs.

[i] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008), p. 49.

[ii] Animerica, ‘Interview with Miyazaki’, Angelfire, 1997 <https://www.angelfire.com/anime/NVOW/Interview1.html> [Accessed 18th January 2023].

[iii] The Humane Society of the United States, About Pigs, 2015 <https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/about-pigs.pdf> [Accessed 18th January 2023], p. 6.

[iv] Paul Wells, pp. 93-95.

[v] F.R. Shapiro, ‘Historical Notes on the Vocabulary of the Women’s Movement’, American Speech, 60.1 (1985), pp. 3-16 (p. 8).

Filmography

Porco Rosso. Dir. Hayao Miyazaki (Studio Ghibli, 1992)

Bibliography

Animerica, ‘Interview with Miyazaki’, Angelfire, 1997 <https://www.angelfire.com/anime/NVOW/Interview1.html> [Accessed 18th January 2023]

The Humane Society of the United States, ‘About Pigs’, 2015 <https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/about-pigs.pdf> [Accessed 18th January 2023]

Shapiro, F.R., ‘Historical Notes on the Vocabulary of the Women’s Movement’, American Speech, 60.1 (1985), pp. 3-16

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008)

Further Reading

Le Blanc, M. and Odell, Studio Ghibli: The Films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata (Harpenden: Oldcastle Books, 2019)

Moist, K.M. and Bartholow, M., ‘When pigs fly: anime, auteurism, and Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso’, Animation, 2.1 (2007) pp. 27-42.

Smyth, Natalie, ‘Human and animal Transfiguration in Spirited Away’, Zooscope, 2014 <https://zooscope.group.shef.ac.uk/spirited-away-dir-hayao-miyazaki-studio-ghibli-2001/> [Accessed 18th January 2023]

Willett, J., The Male Chauvinist Pig: A History (Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2021)

World Animal Protection, ‘Lazy Filthy Pigs? Think Again’, 2016 <https://www.worldanimalprotection.ca/news/lazy-filthy-pigs-think-again#:~:text=Pigs%20are%20often%20associated%20with,’lazy’%20and%20’greedy> [Accessed 18th January 2023]