There are two kinds of pigs that make an appearance in Okja; genetically modified super-pigs and greedy, corporate capitalist pigs. The slaughterhouse scene forces the viewer to dispel any false idealism surrounding the reality of the meat industry, an explicit criticism of how human exceptionalist thinking blended with modern ‘capitalist delirium’ [1] has ruined the innocence of human-animal relations.

This scene opens with an overhead reaction-shot of Mija emerging from the mist and hesitantly raising her eyes towards the camera in horror as a non-diegetic, discordant reverb amplifies the dark apprehension that begins to creep up on the viewer as we remain unaware of the cruelty lurking behind the stationary camera. The tension that is caused by this alienation of the audience is brutally severed when the camera cuts to a low-angle shot from beneath Mija as the hazy forms of limp, hanging carcasses of dead superpigs looming overhead come into focus. The unnatural camera angles used in this nauseating reveal physically diminish both Mija and the viewer, distorting the realism of the scene and lending a nightmarish feel to a sequence that is haunted by the ghostly presence of superpigs, particularly jarring in contrast to the swarm of animals outside awaiting their death.

The surreal atmosphere is elevated by the point of view shot from Mijas perspective, an innocent young girl from a rural idyll who has been thrust into the cut-throat world of capitalist America and is exposed to the horrors of the slaughterhouse for the first time. This provides a particularly eye-opening exploration of human-animal relations as the viewer is reintroduced to the harsh reality of the cruelty intrinsic to the meat industry through a child’s eyes as if for the first time, causing us to question our passivity in accepting this needless loss of animal life purely for human pleasure. The naturalisation of the meat industry promotes the worrying representation of animality as meat designed for human consumption as the gruesome image of slabs of flesh dangling from a butcher’s ceiling has been made recognisable in a western consumerist society, remaining consistently culturally acceptable. By forcing us to recognise that we are aware of the inherent horrors behind the meat industry yet remain passive, Joon-ho raises ontological questions surrounding empathy, particularly human treatment of the animal ‘other’ whom we consider to be below us in the discourse of species, an anthropocentric belief that is reductive of profound animal reality and preserves human exceptionalism.

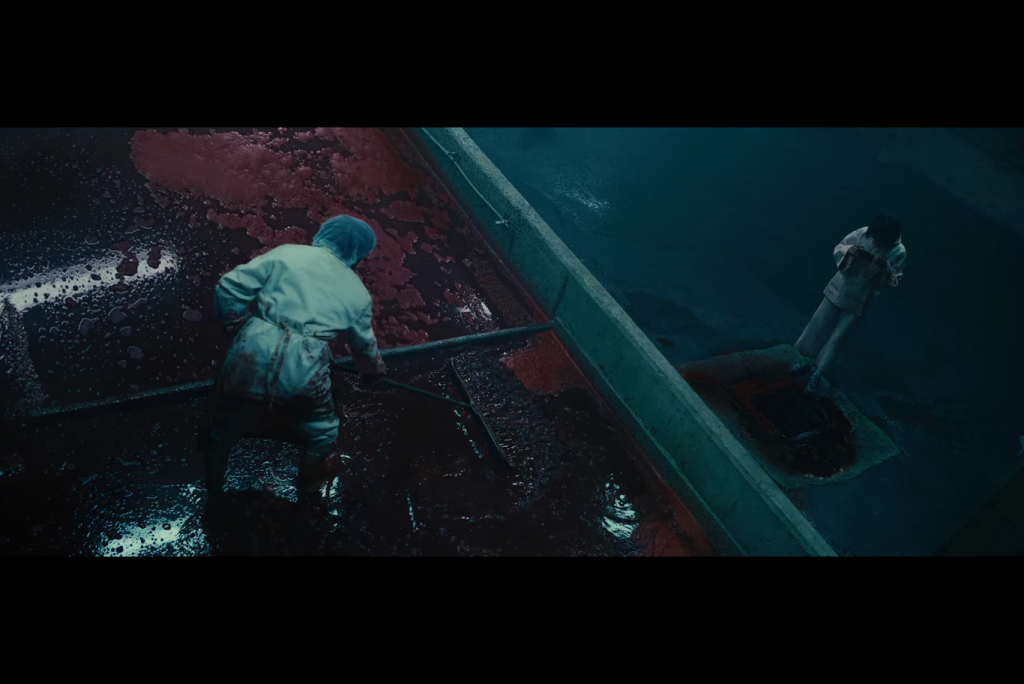

FIGURE 3 shows a worker sweeping up the blood of superpigs

The disquieting surrealism is heightened by the visual elements of the following sequence as we watch a worker sweep a pool of thick, frothing red blood from an overhead angle. The blood is almost luminous as it clashes against the bleak blue-tinged greys of the room, disrupting the cool cast the scene is washed with and infusing the shot with a gothic overtone. The eerieness of this grating colour contrast creates the uncanny sense of a heightened, dystopian reality as we are shown the raw and unfiltered core of the meat industry as it is stripped away of any cheery, false pretences. The boldly stark visuals and sloshing sound effects tap into the audience’s squeamishness as we are refused the comfort of naturalising the consequences of the meat industry as the superpigs have been rendered to merely puddles of blood. Dangerous anthropocentric thinking blended with this insatiable hypermodern technology promotes a destructive relationship between humanity and nature and threatens the complete loss of authentic connection to our environment. This disconnect fuels the ‘capitalist delirium’ that is detrimental to healing the once innocent human-animal relations that have been soured by western consumerist culture.

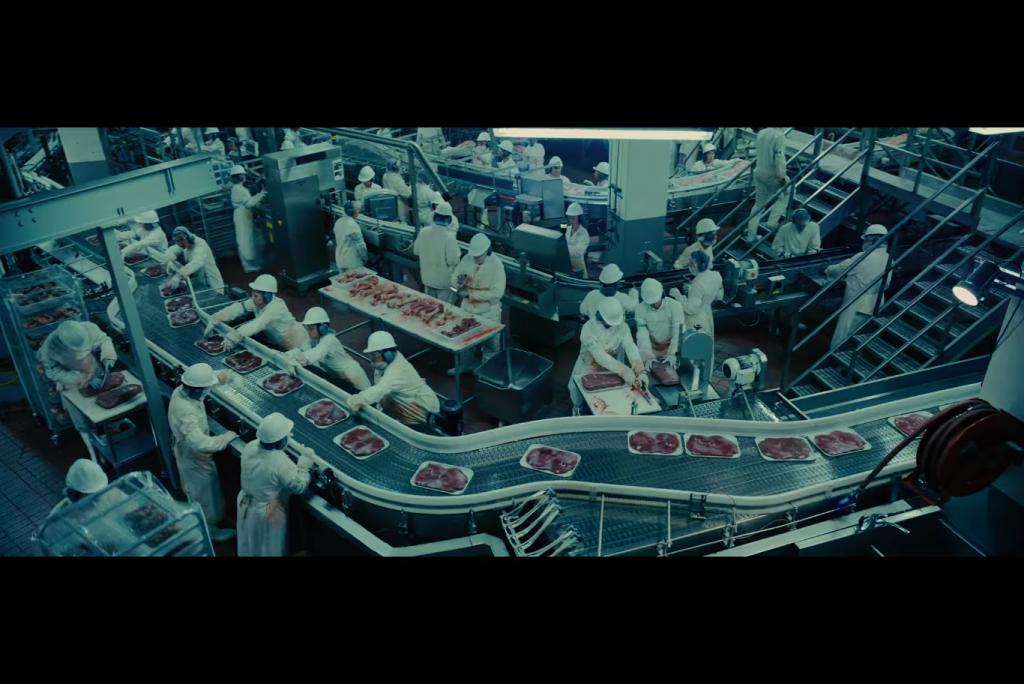

As the scene continues, we are forced to acknowledge that this chilling rendering of animality is not a distant dystopia as we are confronted with images we recognise from the modern meat industry assembly-line, uncomfortably aligning our reality with the harrowing cinematic world of Okja. This parallel to contemporary western society is underpinned by the tracking shot that follows Mija around the factory as the jerky camera movement visually alludes to undercover documentaries that infiltrate corporate farms to expose the brutal, ruthless methods implemented. This startling switch of filming style provides a new perspective on the meat industry as we are assaulted with overwhelming rows of identical workers and slabs of meat, a visual dichotomy of life and death yet both human and animal are victims of the ‘capitalist delirium’ that has broken down positive human-animal relations. In the well-oiled machine of the capitalist meat industry whose only concern is to churn out vast quantities of produce, both humans and animals are seen as a commodity where humans are only useful as working labour in the proletariat and animals are merely seen as a commodity for capitalists to seize and the consumer to devour, not sentient beings capable of emotion. Through a Marxist lens, we are faced with the issue of class, a social inequality that only benefits the rich and powerful bourgeoisie and is often overlooked when exploring the meat industry as both the vulnerable lower class and animals become hegemonised, further complicating human-animal distinctions.

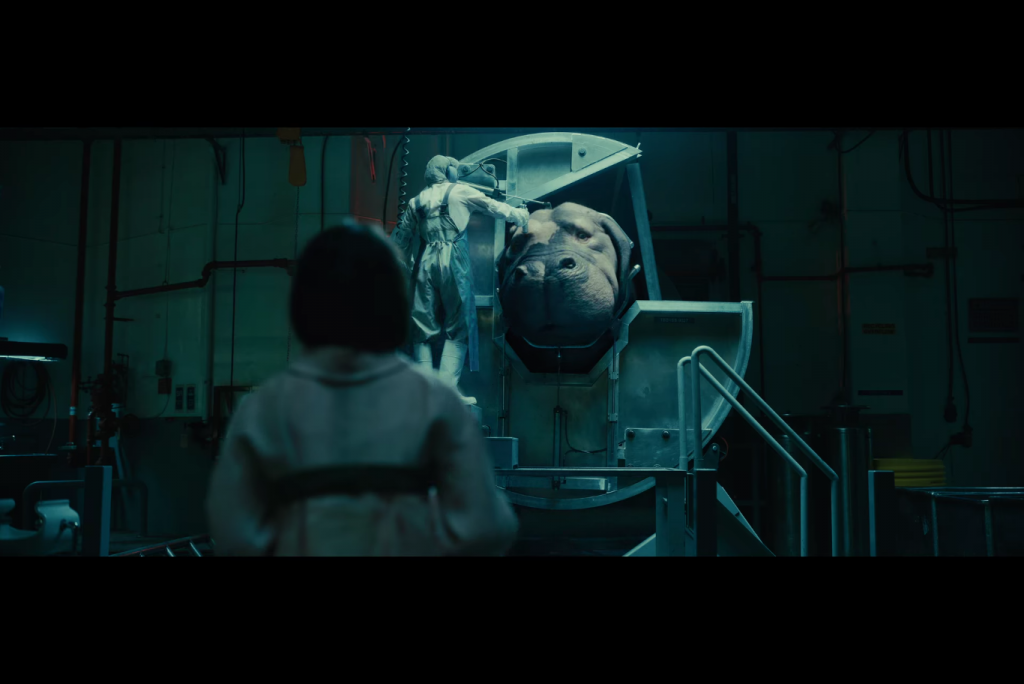

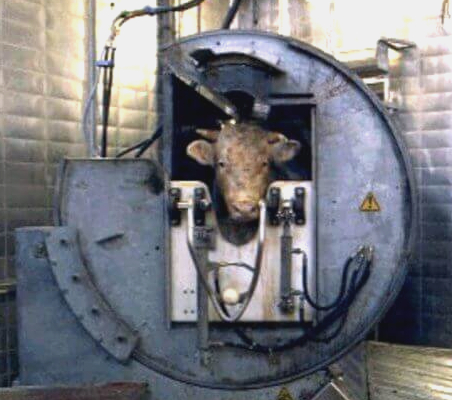

The scene refuses to allow us to separate meat from the animal as the camera becomes stationary in an over-the-shoulder shot where a superpig is fiercely illuminated by fluorescent hard lighting, bringing the animal into sharp focus in contrast to Mija’s out-of-focus blurry outline. Desperation and anguish are shown in the superpigs emotively animated, anthropomorphic eyes, which instantly turn blank as the diegetic sound of a gunshot sharply pierces the soft background machinery noise and the flesh of the superpig. The emotional intelligence embodied in this ‘humanised animal’ [3] serves as a revision of the discourse of species as we watch this superpig display intense emotional capacity and intelligence, a trait that is valued by our own egotistical, narcissistic human exceptionalism. This blurring of binaries between human and animal suggests that the concept of absolute, radical differences in species that have been enforced by the capitalist meat industry are utterly flawed, concocted to absolve the guilt of the consumer and to conceal the profound reality of animals. The mutual recognition in the gaze between girl and superpig, human and animal, forms an intimate emotional mirror as ‘seeing our own look returned to us may not signal human alienation from the animal world’ [4], making it impossible to disentangle ourselves from our affinity with animals and therefore undermining fragile human-animal oppositions.

Bibliography

[1] Cooper, Melinda. Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era (University of Washington Press:2008) pg. 12

[2] Geyrhalter, Nikolaus dir. Our Daily Bread (Icarus Films 2005)

[3] Wolfe, Cary., Animal Rites : American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) pg. 101

[4] Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film LOCATIONS (Reaktion books:2002) pg. 71