‘Of Mice and Men’ (1992) is a film adaptation of the novel by John Steinbeck, which is set in 1930s America during the Great Depression. The film follows the lives of George and Lennie, two ranch workers who struggle to fulfil their ideal of the American dream, which is to acquire their own land.

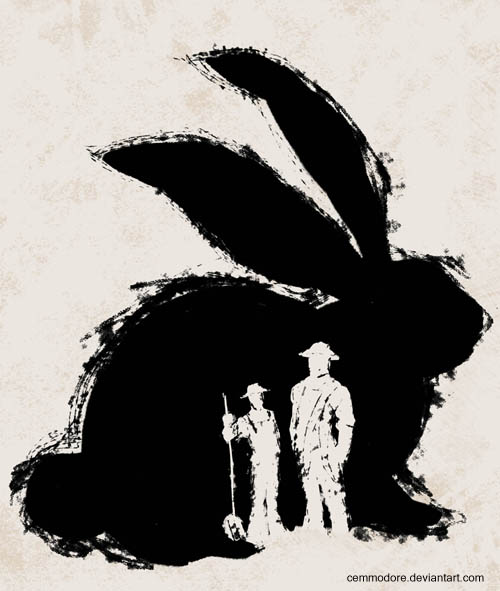

Animals are frequently used within the film in order to symbolise the suffering of the human characters, who are made to work like farm animals and are ‘canned’ and left to fend for themselves if they cannot fulfil a labouring purpose. Animals are also used to describe characters such as Lennie, who has a severe learning difficulty and is completely dependent on George, who orders him around like a pet. He also uses Lennie’s strength in order to gain jobs saying that he is as strong as a bull. Lennie is also unaware of his own strength, such as when he crushes a mouse and puppy, which foreshadows the murder of Curly’s wife, in order to show how he reacts instinctually to fear like an animal, by using violence and then running away. By describing Lennie like an animal, it also makes him appear vulnerable, as despite his destructive actions, he is the most compassionate within the film and cares for characters who appear lonely, as well as showing genuine compassion towards animals.

The style of the film with the use of dark lighting and grey colours mirrors the bleak, mundane and cyclical lives of the ranch workers, who have little goals to strive for apart from earning enough money to survive. There is also repetitive use of locations such as the ranch house and the creek at the beginning and end of the film to show that the American dream is unrealistic, and the characters only end up where they started or in a worse position, such as Candy who is without a dog and George who is without his companion.

Hands are often used as a repetitive symbol for labour, such as when Lennie crushes Curley’s hand, who wears a glove filled with Vaseline for his wife, however when his wife dies, he doesn’t touch her, showing the lack of genuine human connection within the characters, who often own and control people for their own satisfaction like pets. This is shown as, like Candy’s dog, Curly’s wife doesn’t have a name. Hands are also used as a symbol for the increasing mechanisation within agriculture, which forced many farmers off the land. This is shown when Curly, after Lennie has crushed his hand, is told that he must keep this a secret and say that he got his hand caught in a machine, similar to how candy got his hand destroyed in an accident with a machine.

From a Marxist perspective, the workers are mistreated and dehumanised by the bourgeoisie, represented by the figure of the boss. The workers are based on a hierarchical ranking according to gender, race and wealth such as Crooks, the black stable hand who is spoken to with racist, dehumanising language and is segregated from the other workers, as he must sleep in his own house next to the stables. This further aligns him with the animals in the film by his prejudicial discrimination.

There is a strong link between Candy’s dog and Lennie within the film. Candy’s dog is used as a symbol for the mistreatment of vulnerable humans in American society in the 1930s, especially old people who when they are unable to perform a labouring purpose are ‘canned’ and essentially left to fend for themselves, many ending up homeless and poor. The governmental system figuratively shoots them in the back of the head just like Carlson shoots Candy’s old dog in the back of the head with his luger. I would argue that this scene creates more of an emotional and empathetic response to the viewers than the scene when Lennie is shot.

The scene begins with a mid shot of Candy’s dog, which then tilts upwards to Candy as they enter the bunkhouse. This gives greater significance to Candy’s dog, foreshadowing the dog’s death as it will later exit the bunkhouse to be killed. This also aligns the dog with Candy, an old man who is without the use of his arm who enters the bunkhouse stating that he has gut ache. When Carlson says to Candy that the dog ‘stinks’ and that Candy can have one of Slim’s puppies that he needs to get rid of, as he drowned many of them because nobody could look after them, this shows the unemotional connection that the ranch workers have towards animals, who they see through merely practical purposes.

Candy feels pressured into deciding and realises due to his old age and inferiority in comparison to the younger, stronger men in the bunkhouse that he is as powerless as the dog is. This is shown as he gazes into the eyes of his dog. Berger states that animals do ‘not reserve a special look for man. But by no other species except man will the animal’s look be recognized as familiar. Other animals are held by the look. Man becomes aware of himself returning the look ’. As Candy gazes into the dog’s eyes, he sees himself reflected back and is conscious of the fact that the dog represents his fate when he becomes too old to sweep the bunkhouse.

This is shown later in the film when he wants to join George and Lennie in their American dream when he says ‘you seen what they done to my dog. They said he wasn’t no good no more. I wish somebody’d shoot me when I ain’t no good but they won’t do that. They’ll can me, and I ain’t gonna have no place to go.’ The use of silence within the scene has a strong impact in voicing not only Candy’s dogs inability to have agency in the scene, as his life is placed into the hands of Carlson, but it also shows the lack of empathy of the other ranch workers, who decide to play a game of ‘solitaire’ rather than comfort Candy, who lies on his bed speechless. The dog is taken outside by Carlson and Slim tells him to ‘get a shovel’ which shows the insensitive dispatching of life. Whilst the audience are waiting tensely for the dog to be shot, the other ranch workers play cards, only occasionally glancing back at Candy as the only sound is the background noise of crickets, which makes the atmosphere uncomfortable. The use of the game ‘solitaire’ which sounds like solitary, shows the lack of human connection and empathy amongst the ranch workers, who through the Darwinian concept of the survival of the fittest must dispatch those who appear weak and unable to fend for themselves; this practical and unemotional thinking however leads to violence and loneliness.

This is symbolised by Candy who is lying on his bed with his arms hugging himself, as nobody is there to offer him a hug. He almost appears lifeless like he is lain in a coffin, which foreshadows his isolated death when his dream is destroyed. Candy also appears out of focus frequently within the scene to show that his feelings are made unimportant.

When the gunshot is finally heard Candy winces as he imagines the pain that the dog must have gone through, it is as if Candy himself has been shot. The dog is taken away from the scene for ethical reasons so that we are unable to see him being shot, however this desensitises and takes the agency away from the animal as Carlson’s atrocious act go unseen. This transforms the animal image into becoming a ‘form of rupture in the field of representation … a floating or unstable signifier ’. As the dog is taken out of the bunkhouse, the audience’s attention is also taken away from the dog and is focused on Candy. Therefore, our attention ‘is constantly drawn beyond the image and, in that sense, beyond the aesthetic and semiotic framework of the film. This unavoidable state of being drawn behind the animal’s film image is the basis of the conflict over the control of animal imagery’. I believe that the scene in which Candy’s dog is shot is more emotional than when Lennie is shot due to the length of time in which the dogs death is prolonged, as well as the lack of agency that Candy’s dog has to make a decision about its own life and the fact that the dogs death is taken from the audience’s attention.

However, one could also argue that Lennie is powerless over his own death as his killing of the animals and Curley’s wife is a response to fear and his acts of violence appear out of his control as an emotional response where he is unaware of his own strength. His death at the end of the film is taken into George’s hands, who appears to become a godlike figure who like Candy, who wishes ‘they’d let me shoot my own dog’ wants to take responsibility in how Lennie must die, rather than let Curly and the ranch workers shoot Lennie in the guts.

(George shoots Lennie)

George becomes the hero at the end of the film, as Lennie gains a sense of freedom in his death as George tells him to face towards the picturesque scene of the creek and to imagine his dream of tending the rabbits on the farm. George is aware that Lennie must die and that his dream of owning his own land with Lennie has become crushed, as Lennie wouldn’t be able to tend to rabbits without crushing them. Dreams are often used as a distraction within the film from the harsh realities of life, such as Curly’s wife who dreams of being a movie star and eventually gains the attention which she craves only through death.

George shoots Lennie by the Creek, the place that the pair visited earlier on in the narrative where George warns Lennie that if anything bad happens to him he must return to this place, which gives a cyclical structure to the plot and also shows that the fatal death of Lennie was predetermined and they were destined for failure. George uses the same gun that Carlson uses to shoot Candy’s dog which creates a link between the two. In the same way that Carlson tells Candy that his dog ‘won’t even feel it’ and ‘ain’t no good to himself’ Slim also uses these phrases when describing Lennie. Lennie is essentially ‘put down’ by George.

When George stands up after crying over Lennie’s shoulder, the scene quickly cuts to a wide shot of George shooting Lennie in the back of the head. Only three seconds pass between George standing up with the gun out of shot and the eventual death of Lennie, which makes the killing appear practical and emotionless in comparison to the drawn out scene between Candy and his dog. The fact that we see Lennie being shot in the head and we only heard Candy’s dog being shot makes it feel like Lennie’s death is the missing frames in the scene of Candy’s dogs death, especially as Lennie is described and acts like George’s dog within the film.

The symbolic image of being shot in the back of the head whilst dreaming creates a pessimistic critique of the American dream. Through linking the human characters discrimination and laborious life to that of the animals, the film creates a wider critique of American society showing that the people on the ranch have such a bleak, mundane life and are so unlikely to achieve the unrealistic ideals of the American dream, that they would have a greater chance of achieving peace through death. This is especially true if they are vulnerable members of society as they are treated like their life is invaluable because they have no ability to contribute to society through labour.

Bibliography

John, Berger,John ‘Why look at animals’ (2009) worldviews Vol. 9, No.2

Burt, Jonathan ‘Animals in film’ Reaktion Books (2002)