Chloe Zhao’s 2021 feature film Nomadland explores the conditions of the American landscape, nomadic experiences and estranged relationships of belonging amidst continuously unstable socio-political and economic conditions of the 21st century. Zhao blends a naturalist style of filmmaking with observational realism to explore the stories of nomads living in rural America, employing non-actors to play themselves alongside Frances McDormand, who takes on the role of the fictionalised Fern, a middle-aged woman forced out of her home in 2011 after the economic crash. In the face of this and the death of her husband, Fern sells her belongings and moves into her van, where she sets off in search of seasonal work. While animals do not play a central role in the film’s narrative, their presence often seems to echo the film’s very concerns, whether it be a flight of swallows embodying the nomad’s philosophy in their migratory movement, a bison wandering through ancient forests, or horses, geese and farm animals confined behind fences. These fragmented scenes capture and reflect the conditions of the nomads, whose ethos of minimalism and movement is poetically conflated with the existence of animals at the film’s periphery. Running against these symbols of freedom and movement is a less romantic projection of a different group of the ‘other’ American public, such as Fern’s sister. These characters come to be defined by home ownership, debt and stagnance. The presence of the animals reminds the audience of the construction of social norms and behaviours. Where a farm fence confines the animal, the human is also by the white picket fence. As the world continues to insist on immobility and dedication to the domestic, Fern and her fellow nomads’ affinity with wild animals projects a message concerning freedom and liberation through the rejection of normality.

In the film, swallows work as a repeated motif and poetic metaphor. Zhao’s lyrical treatment of the birds reflects themes of escapism, enabling a broader understanding of the nomads as a group defined by collectivism and migratory habits, ultimately enabling Fern to find belonging in nomadism. While staying with a group of nomads at a gathering in Arizona, Fern meets Swankie, who reveals to Fern that she has eight months to live. Swankie vows to return to Alaska to visit the swallows she has seen once before, explaining to Fern, ‘I’m not going to spend any more time indoors in a hospital. No thanks.’ In rejecting medical care, Swankie reveals a preference for pockets of a declining natural world inhabited by animals, as she recalls seeing ‘moose in the wild… A moose family on a river in Idaho. Big white pelicans, landing six feet over my kayak on a lake in Colorado.’ Swankie’s affinity with the animals and her adventure to be with them in death reflects the nomad’s navigation of the landscape in search of alternative belongings. Swankie reflects on a utopian space where she believes she can finally find liberation away from the demands of the American political landscape. The swallows in Alaska, notably not in the landscape Fern, Swankie and their fellow nomads inhabit, suggest an alternative, paradisiacal space. A notion of escapism emerges here through Swankie’s affinity with the swallows, where the birds become symbolic in their flight of a metaphorical escape. Swankie’s final journey to find them reflects her escape from the brutal economic demands of the American political system.

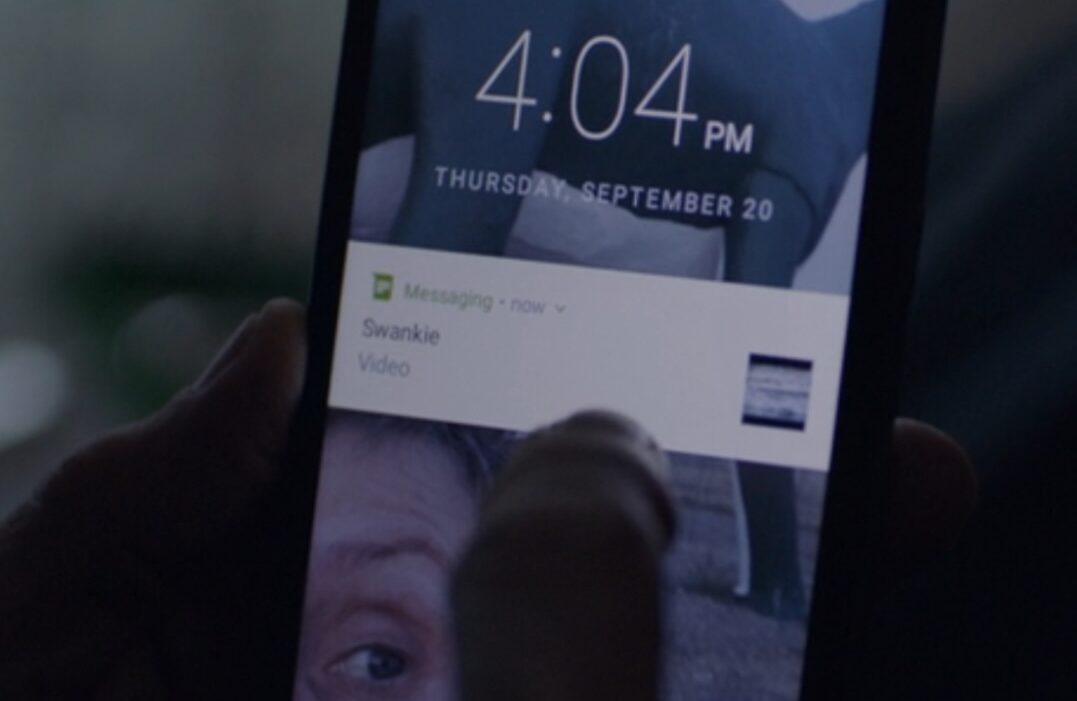

Swankie’s initial description to Fern of the Swallow’s egg shells, painfully delicate falling into the water after the new chicks have hatched, becomes reminiscent of the socio-economic fragility experienced by Fern. This escapism is embodied after Swankie’s departure when Fern receives a message on her phone months later. Shaky camera phone footage captures the swallows in their flight. Instead of opting to film the scene in line with the rest of the film’s heightened poetic style, Zhao settles for a more observational take, as the audience witnesses the scene through Swanky’s camera and concurrently Fern’s phone (fig. 4). Swankie’s affinity with the birds is displayed to the audience in an autonomous style, not stylistically heightened by the film’s stylistic concerns but presented with quiet honesty; the swallows, in this sense, seem further away than ever, accessible only to Swankie on her lone pilgrimage. This poetic treatment of the swallows as a motif reflects Zhao’s avoidance of the inherently political nature of migration and nomadism. She ignores the political ramifications of migration and American capitalism in Swankie’s rejection of medical care and instead projects Swankie as determined to find peace through her affinity with animals. As one critic describes the nomad’s lifestyle, ‘the choice to leave is not escapism but flight with an immediate political potential: defiance by disentangling from the customary capitalist (produce-consume-die) life.’1

Figures 1 and 2. Swankie holds the swallows egg before placing it back gently in the water

Figures 3 and 4. Fern receives a video from Swankie of the swallows in Alaska

Swallows are a migratory species, bound together in flight and defined by their movement mirroring the nomad’s existence. The OED defines the adjective and noun ‘migratory’ as ‘of an animal: characterised by or given to a migration, esp. of a periodic or seasonal kind’; it charts the terms first used to the description given to migratory birds, like swallows.2 The second definition the OED cites relates migration to people: ‘of a person, a people, etc.: moving temporarily or seasonally from place to place; nomadic; given to travelling’.3 The film’s poetic naturalism ties the nomads wandering to the swallows’ flight. Swankie’s affinity with the swallows ultimately aids Fern in her process of ‘becoming’ or finding peace in nomadism, something the film proposes is both a condition defined by outsiderness and collectivity. As Fern explores the landscape on her own after leaving the nomad gathering hosted by Bob Wells, she becomes symbolic of the swallows Swankie describes: breaking out of her shell and ‘leaving the nest’. Fern’s navigation of the American landscape in the film charts a linear process from ‘un-belonging’ to ‘belonging’ at the film’s end.

Figures 5 and 6. The swallows and their nests as captured by Swankies phone camera.

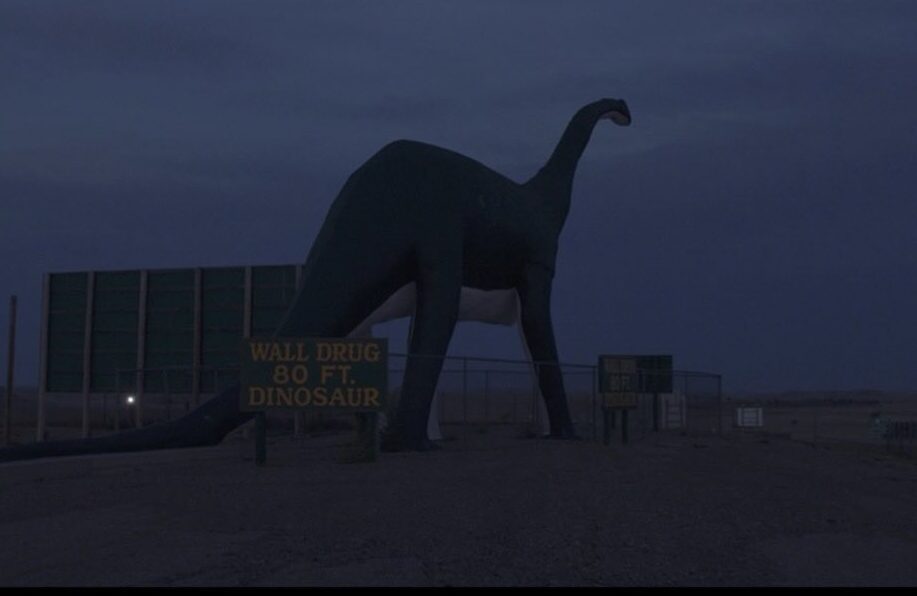

Zhao’s employment of animals continues to act as a poignant symbol of the conditions of the nomads. Where Swankie’s escape to the swallows embodies the nomad’s idealism, other instances of animal encounters work to reflect the threats posed to a nomadic existence. This is captured in Fern’s interest in a statue of a dinosaur that she returns to visit, gazing up in affinity at the giant that stands cemented into the landscape, a reminder of species extinction, or elsewhere when Fern encounters a lone Bison on the side of the road. (figs. 7 and 8, and fig. 10).

Figures 7 and 8. The dinosaur at Wall Drug visited first by Fern and Dave, and then by Fern alone.

The bison, a recurring symbol of early America (see fig. 10), becomes reminiscent of both the pioneers Fern is later referred to and, like the dinosaur, another species threatened by extinction.4 In this scene, poetically inflated with the non-diegetic soundtrack, Fern looks onward at the animal, alone and wandering much like herself, lost within a declining natural world; Fern is revealed to be more like the animals she encounters in the film than the humans. Thomas Dai notes how Fern and the Bison are connected in terms of a journey, writing, ‘for a moment, the two travellers are caught moving at different paces but in the same, general direction, adherents of a lost periodicity’.5 At this moment, Fern imitates the Bison itself; the interaction displays a peaceful coexistence and mutual understanding between two beings that abrasively juxtaposes Fern’s interaction with other non-nomadic humans. When visiting her sister’s house in middle-class suburbia, Fern is made visibly uncomfortable by the conversation about home ownership and real estate, clearly ‘othered’ against her sister’s friends, who remain committed to the idealised American lifestyle. As one reviewer notes, the film explores a sense of ‘loss and detachment from the settled world of the middle class, capitalist and comfortable America’; the moment Fern flees back to her van reveals her fears of entrapment.6 Escaping and returning to the natural world relieves Fern and the audience. In the film’s negotiations of ideas surrounding house, home and a more fundamental sense of belonging, Fern finds affinity with animals like the bison, not constrained to home ownership or other more hegemonic standards of existence and redefines what belonging might look like as a rejection of such a system.

The film’s portrayal of animals often ties into its concern with a binary of freedom versus confinement. When, at one point, Fern joins a gathering of nomads, a speech is made about the treatment of American workers. Language reflects the threat of passivity in humans and animals, where one nomad describes ‘the yoke of tyranny’, and the worker is compared to a workhorse ‘willing to work itself to death’. The nomads are thus projected as escaping confinement through their rejection of normality. The film reveals in these references to animals its paradoxical interest in capitalism, never showing if the nomads are confined or liberated by the conditions of 21st-century America. One critic notes how Fern’s story is ‘one of personal responsibility and freedom… the crisis of capitalism is also the solution’, underling the film’s hesitance to critique late capitalism and opting instead for a more muddied intrigue.7 In this sense, the film concerns itself with a poetic, rather than political, portrayal of America in the 21st century. The landscape captured is not scarred by 20th-century industrial conquest but rather shaped by it, much like the nomads themselves, who are understood to be ‘motivated by individual grief’ rather than ‘economic woes’.8 One critic writes, ‘the tableau she paints with her words is as entrancing as the film’s lush landscape cinematography’.9 Zhao’s poetic take casts the nomadic experience as one that celebrates the beauty of the landscape and the freedom of movement. The nomad’s decision to reject normality reflects the free yet solitary existence of migrating animals like the bison.

While animals are utilised to reflect naturalism and the nomad’s freedom, images of confined or entrapped animals echo the film’s concerns with conformity, immobility and entrapment by capitalism. Where the bison and swallow in the film relate to the nomads of their freedom and liberation, Zhao’s inclusion of numerous animals entrapment on farms or zoos could be viewed as a reflection of the confinement experienced by the non-nomads of the film.

Figures 9 and 10. Fern projected against the vast American landscape before she sees the lone and wandering Bison.

These occur most notably with Dave, a friend and potential romantic partner Fern finds company with on the road. Visiting a roadside zoo, Fern and Dave see an encaged python and alligator; entertained by the visit, the two are drawn together by their juxtaposition with the state of the animals in the zoo. Where the crocodile sits behind a glass window (fig. 12), Dave and Fern return to their vans on the road, eating dinner against the vast and open desert (fig.13).

Figures 11 and 12. The snake and alligator Dave and Fern visit at the zoo.

Figures 13 and 14. Fern and Dave eat dinner before Dave leaves to return home for good.

When Dave receives news he is soon to be a grandfather, he decides to return home (fig. 14). Once again, Fern is faced with an invite back into the domestic, suburban life she has abandoned. Dave begins to symbolise a doorway for Fern to leave nomadism and return to a stable life. Yet, he also embodies the potential entrapment of Fern, intrinsically linked in a patriarchal fashion to the threat of domestic confinement. When Fern finally visits Dave for Thanksgiving, the animals-in-captivity motifs are repeated. The farm animals seem to suggest that if Fern did choose a more normative life, adhering to patriarchal and capitalist norms and standards, she too would become entrapped (figs. 15 and 16). Like in the visit to her sister, the farm gates, or picket fence, symbolise the domestic world in which Dave and Fern are ‘supposed’ to belong. Where Fern’s poetic and liberated existence mirrors that of the bison, the entrapped animals reflect the confinement of the non-nomadic life that Fern has rejected. The portrayal of confined animals contrasts with the migrating swallows and bison, symbolising Fern’s nomadic existence.

Figures 15 and 16. Dave and Fern sit with the baby, a domestic scene that reflects Fern’s potential to resettle.

Figures 17 and 18. Farm animals at Dave’s house.

Zhao’s use of animals is core to the film’s concern with entrapment, presenting to the audience several binary oppositions to reveal a tension between perceptions of freedom and constraint. Contrasted against the freedom the swallows and the bison embody are fragmented scenes which convey animals encaptured behind fences or imprisoned in cages encountered by Fern. In these comparisons, the film points to a hegemonic conversation surrounding belonging and the implication that humanness equates to static stability. Confinement and captivity are established as a central theme and notion affecting not only the film’s animals but also the nomads themselves, who become symbolic of a struggle to escape from the fabric of American consumer capitalist society in favour of weaving their own non-normative sense of belonging.

Primary source:

Nomadland, dir. by Chloe Zhao (Searchlight Pictures, 2020)

Bibliography:

Dai, Thomas, ‘Film Review: Nomadland’, Terrain, 2022 <https://www.terrain.org/2021/reviews-reads/Nomadland/> [accessed 12 December 2023]

Gupta, Arun and Fawcett, Michelle, ‘The Neoliberal Fantasy at the Heart of “Nomadland”’, In These Times, 2021, <https://inthesetimes.com/article/Nomadland-chloe-zhao-oscars-film-culture-amazon-workers> [accessed 13 December 2023]

Jasper, David, ‘Nomadland: A Film by Chloé Zhao’, Expository Times, 134.12, (2023, 539–42 (p.539) <https://doi.org/10.1177/00145246231156324> [accessed 10 January 2024]

Larsen, Josh, ‘Nomadland’, Larsen on Film, 2020, <https://www.larsenonfilm.com/Nomadland> [accessed 12 December 2023]

Maglione, Giuseppe, ‘Film Review: Chloé Zhao, Nomadland’, Crime, Media, Culture, 18.2, (2022) <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/17416590211054338> [accessed 12 December 2023]

McHugh, Jess ‘Once nearly extinct, bison are now climate heroes’, The Washington Post, (2022) <https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2022/07/13/bison-buffalo-oklahoma-extinct-climate-change/> [accessed 14 January 2024]

OED ‘migratory’, n.,1. a. www.oed.com [accessed 12 January 2024]

OED ‘migratory’, n.,1. b. www.oed.com [accessed 12 January 2024]

Further Reading:

‘Nomadland: New Naturalism’, Theasc.com, 2021 <https://theasc.com/articles/nomadland-new-naturalism> [accessed 12 December 2023]

Dams, Tim, ‘Screen Craft: How DoP Joshua James Richards Brought “Nomadland” to Vivid Life’, Screen Daily, 2023 <https://www.screendaily.com/features/screen-craft-how-dop-joshua-james-richards-brought-nomadland-to-vivid-life/5157796.article> [accessed 12 December 2023]

Rose, Steve, ‘Nomadland: Is “Structured Reality” Cinema an Exciting New Trend, or Simply Fake News?’, The Guardian, 2021<https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/apr/28/nomadland-is-structured-reality-cinema-an-exciting-new-trend-or-simply-fake-news> [accessed 13 December 2023]

- Giuseppe Maglione, ‘Film Review: Chloé Zhao, Nomadland’, Crime, Media, Culture, 18.2, (2022) <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/17416590211054338> [accessed 12 December 2023]. ↩︎

- OED ‘migratory’, n.,1. a. www.oed.com [accessed 12 January 2024]. ↩︎

- OED ‘migratory’, n.,1. b. www.oed.com [accessed 12 January 2024]. ↩︎

- Jess McHugh, ’Once nearly extinct, bison are now climate heroes’, The Washington Post, (2022) <https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-solutions/2022/07/13/bison-buffalo-oklahoma-extinct-climate-change/> [accessed 14 January 2024]. ↩︎

- Thomas Dai,‘Film Review: Nomadland’, Terrain, 2022 <https://www.terrain.org/2021/reviews-reads/Nomadland/> [accessed 12 December 2023]. ↩︎

- David Jasper, ‘Nomadland: A Film by Chloé Zhao’, Expository Times, 134.12, (2023, 539–42 (p.539) <https://doi.org/10.1177/00145246231156324> [accessed 10 January 2024].

↩︎ - Arun Gupta, Michelle Fawcett, ‘The Neoliberal Fantasy at the Heart of “Nomadland”’, In These Times, 2021,

<https://inthesetimes.com/article/Nomadland-chloe-zhao-oscars-film-culture-amazon-workers> [accessed 13 December 2023]. ↩︎ - ibid. ↩︎

- Josh Larsen, ‘Nomadland’, Larsen on Film, 2020, <https://www.larsenonfilm.com/Nomadland> [accessed 12 December 2023]. ↩︎