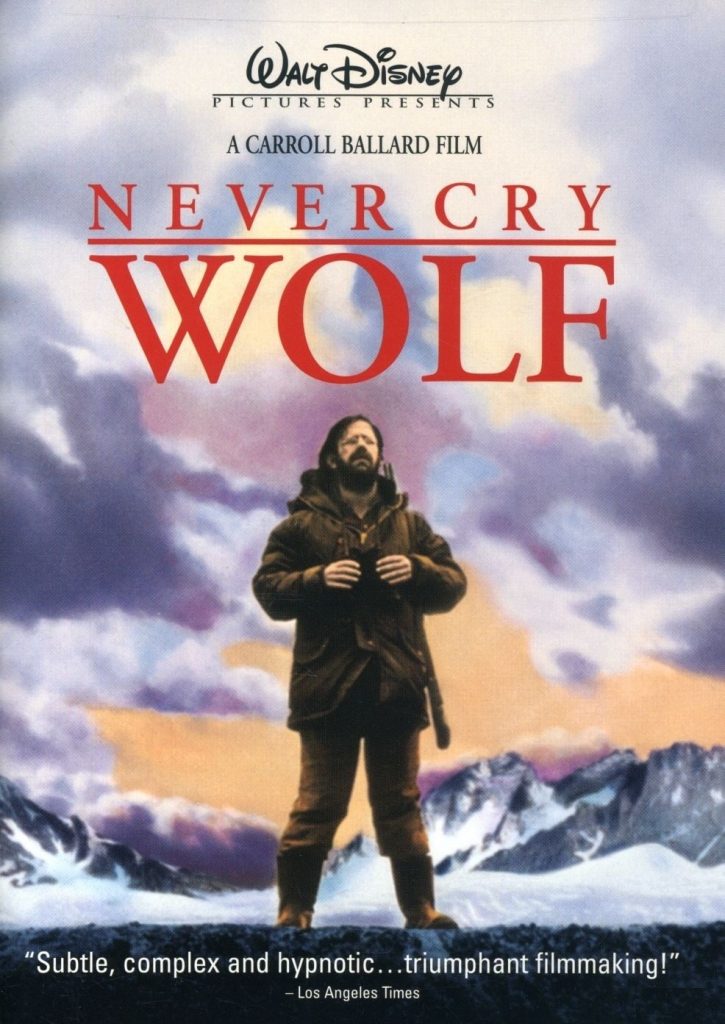

Carroll Ballard’s 1983 adaptation of Farley Mowat’s 1963 dramatised autobiography Never Cry Wolf is as intricate and astonishingly baffling as it is brilliant. The film tells the story of biologist Tyler and his time in the Canadian arctic where he has volunteered to take part in a scientific study of wolves, largely considered by the otherwise bewildered scientists to be the cause of the declining caribou population of the surrounding area. Instead of encountering the ferocious animals of history and myth that confirm the scientists’ hypotheses, however, he finds benign, seemingly simple creatures that live mostly off mice, only hunting and feeding from diseased caribou, helping to preserve the healthy population. Humans themselves, and the looming threat of modernity, become much more dangerous prospects to the natural population. The film’s ecological premise is deeply persuasive, however what becomes much more interesting is the way it struggles to resolve the problem of animal-human relationships and the way they should or even can be semantically and popularly represented and understood – whether through science, myth or emotional investment, if at all. Tyler becomes disillusioned with this task and in the end implies he will return to our flawed, though familiar, modern world.

Disappointing Wildlife

Never Cry Wolf sits very much within the wildlife genre of filmmaking, a diverse form in itself, encompassing both fiction and nonfiction cinema, that, when based in fact, purports to present a kind of reality that is dramatised and framed through “artificial formal inventions” to produce an engaging narrative for the viewer to enjoy. [1] This mix of “science and storytelling” (84), where animal movements are codified “to illustrate general biological facts” (28), allows the filmmaker to communicate the social implications of animal-human relations that are presented in the film more effectively. This is immediately true of Farley Mowat’s original autobiography, whose ecological premise is expressed through a storified version of his time in the Arctic. These so-called facts are often taken for granted, largely left unquestioned by us as the audience, and even if they do hold claims to reality, are manipulated and edited to produce that very familiar feeling of excitement – the realities of “stillness and silence have almost no place in wildlife film” (4). But the wolves in Ballard’s film are still, they are silent, and for the most part remain so throughout – an uninterrupted benign presence that go about their business, filmed with lethargically long and unfamiliar slow takes. Never Cry Wolf engages very directly with these traditional narrative tropes of wildlife filmmaking – the camera’s gaze itself adds a cinematic layer to Mowat’s memoir, and as such Ballard is able to offer a critique of animal representations in popular culture that Mowat is unable to. What becomes interesting is that through reacting to these generic traditions, Ballard dramatises an already heavily dramatised text. Subverting expectation is this way is complicated by our human observer and point of reference Tyler, who must slowly discover that these wolves do not fit into this stereotypical mould of aggressive animal behaviour, which in itself aligns with our own hopes of cinematic spectacle. His journey into the Canadian wilderness is more reminiscent of the adventure genre, where he positions himself as the hero at the centre of the narrative, hoping to defeat the villains of this unknown exotic landscape in the dramatic style that thrills audiences. [2] His, and our, expectations are quickly cut short.

Finding Meaning through Subversive Science

This initial hybridity of genres, where the energy of wildlife film is unusually subdued and pitted against the expectant quest narrative of the action-adventure form, propagated by the human protagonist, enhances and demonstrates the effect of the conflict between science and storytelling intrinsic to the wildlife genre itself. We expect the action and spectacle that in our minds are always associated with animals, and why not? Rather than validating itself, the film raises questions of how we should relate to animals and how they should be culturally represented. Part of this answer seems to initially be clear – definitely not through a discourse which represents the wolf as the savage creature we know from myth. The film wants to change this public perception in order to promote an ecologically sustainable relationship with the land and its wildlife. What makes this film so remarkable, however, is that this simple answer becomes a whole lot more complicated.

The film opens on a quiet, oppressively white mountainous landscape, with the spine-tingling high-pitched tones of the mystifying soundtrack framing the opening credits that describe the background to Tyler’s scientific study. The language is immediately emotive and draws on storytelling tropes to dramatically illustrate the importance of this scientific research: the “biological catastrophe” of the declining caribou population is suspected to be a result of “a creature known from story, myth and legend as a ferocious killer. Canis lupis — the wolf.” Although Tyler’s naming of the animal is decidedly scientific, it is dramatically framed through this otherwise mythic discourse that is privileged over any kind of scientific reality – in equally dramatic style, the credits claim that “no scientist” had ever entered into this fabled land of the arctic to observe the wolves in their natural habitat. The spectacular yet quietly haunting cinematography also then reflects this ominous premise; the wolves remain hidden and instead we are introduced to our so-called hero, who tacitly promises us as the expectant regular movie goer – we of course already know exactly how this Hollywood film will end – to defeat the baddies lurking from within. This stuffy, awkward biologist is not our typical Romantic hero, rather he appropriates the title by self-consciously confessing his own desire for it: he remembers his “fantasy […] to go off into the wilderness, and test myself against all the dangerous things lurking there”. Our first glimpse of the infamous animal only comes half an hour in – a long shot where the wolf’s white coat against the grey sky and the impeding mist almost obscures it from view. This distant framing reoccurs often throughout the film, reinforcing the mysticism of the wolf’s quiet presence that the film struggles to reject.

This heroic and animal mythology immediately conflicts his supposed scientific purposes. After his theatrical landing in the middle of this vast emptiness, he stresses the importance of staying “rational”, following all proper scientific procedure, remaining objective and calm as he reads his instructions of examining the contents of a wolf’s stomach. His scientific mode is parodied – his bright yellow trench coat and sour face as he tries to conduct an experiment while his igloo proceeds to melt around him. His first encounter with a wolf is then immediately scientific as he dramatically declares its arrival: “Canus Lupus Arcticus.” This rationality soon dwindles however; he starts to form a strange emotional attachment to the animal where his scientific purpose is mixed with his own weird desire of somehow becoming a wolf itself, as if it is an ideal state of being. Once he decides to break the “rules of the game” (is science a game?) because the wolf is “violating [the] distance principle” (defying human scientific discourse), we see Tyler shamelessly peeing around his tent to mark his territory as well as eating mice, all culminating in his wolf-like naked chasing of the caribou. The slow, predominantly long shots of the wolves finally culminate into a ridiculous though surreal scene showing the spectacle and speed of the chase, beautifully lit in the setting sun. For Tyler, this astonishing dream-like sequence supposedly completes his naively ideal transformation into the mythic wolf.

A comic scene of a pseudoscientific experiment: a nice dinner of mouse for both man and wolf. This scene is immediately followed by a light-hearted juxtaposition of images between the mad intentions of the biologist and the frolicking frivolity of the endearing wolf, a rare insight compared to the many instances of mystic, quiet watching.

This opposing discourse of science and myth shows his struggle to find any exact meaning in the animal – he is in a sense trying to figure out the wolf as a creature, and how the human should relate. As his perceptions of the animal change he tries to align himself with the wolf as a benevolent figure in many ways superior to man. The true source of violence comes from the human, and he realises that the harmful onslaught of modernity is partly through his own interference in the landscape, disillusioning him of his own seemingly positive motives. Pilot Rosie commoditises the wild, aspiring to “bottle the air”, also paving the way for hunters. Modernised Inuit Mike is similarly a hunter, the wolf a means of making money to feed his family – a plain and unavoidable reality that the foreign Tyler wants to deny because he cannot remedy it himself.

‘Act of Watching’

Animals in the film are watched through a lens – through spectacles, notebooks, the camera itself and the implicit sights of the hunter’s gun: the “eyes of a man” – not as they are but as a cultural and social construct, as Nature rather than nature, where “individual perceptions of Nature […] are framed by the broader social process of making meanings”. [3] Tyler searches for a true nature but cannot reach a reality where the animals can be fully understood as they are, disassociated from the human process of signification. He yearns for a language-less discursive mode free of cultural association, the Real space which resists symbolisation, outside of science, emotion, mythology, or the hunter’s gaze. This is crucially separate from cinematic spectacle – the gaze of the camera – and even genre itself: “In the end there were no simple answers. No heroes, no villains, only silence”. The silence demands that we walk away, to stop watching, to stop making meanings, and in other words, to stop being human, if ever we are to fully understand these creatures, who for Tyler have “direct contact with their environment”. Humans cannot, in Akira Mizuta Lippit’s words, “translate that perception into the linguistic registers that constitute understanding”, rather relying on “some form of meditation or allegorization” [4] – something that Tyler must unavoidably come back to in the end, his narration still skewing towards the mythic as he declares his intentions to walk away: “the wolves went off to a wild and distant somewhere”, where he must quickly forget any form of attachment he may have had, because surely the wolves have already done the same.

Never Cry Grizzly

Werner Herzog’s 2005 Grizzly Man is definitely an interesting comparison to this film – its mythic tropes and self-fashioned heroic figure are framed by the documentary style with the director himself narrating a rather less sympathetic version of what he considers the protagonist’s delusions. Both films seem to favour a human-animal distance, but while Ballard ends on a reluctantly mythic note, Grizzly Man defiantly reinforces the image of the animal – here, the bear – as a fabled beast. Treadwell never relinquishes hold of his animalistic sympathies, and though probably more troubling than Tyler’s eventual disenchantment, Treadwell as the engaging, defiant hero must be privileged over his cinematic counterpart. The film is bitingly bitter and cynical, while Ballard rather more gently laments this struggle of the human-animal condition, going against the cinematic spectacle of the wildlife documentary film that Grizzly Man lives up to.

Works Cited

Bousé, Derek, Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000)

Goedeke, Theresa L. & Ann Herda-Rapp, Mad about Wildlife (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2005)

Langford, Barry, Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005)

Lippit, Akira Mizuta, Electric Animal: Towards a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000)

Never Cry Wolf. Dir. Carrol Ballard. Buena Vista Distribution, 1983.

Further Reading

Bousé, Derek, Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000)

Chris, Cynthia, Watching Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006)

Mowat, Farley, Never Cry Wolf: The Amazing True Story of Life Among Arctic Wolves (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1996)

Never Cry Wolf, Internet Movie Data Base https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086005/?ref_=ttqt_qt_tt [accessed 26 Nov 14]

[1] Derek Bousé, Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), p. 14.

[2] Barry Langford, Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), p. 238.

[3] Theresa L. Goedeke & Ann Herda-Rapp, Mad about Wildlife (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2005), p. 4.

[4] Akira Mizuta Lippit, Electric Animal: Towards a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p. 6.