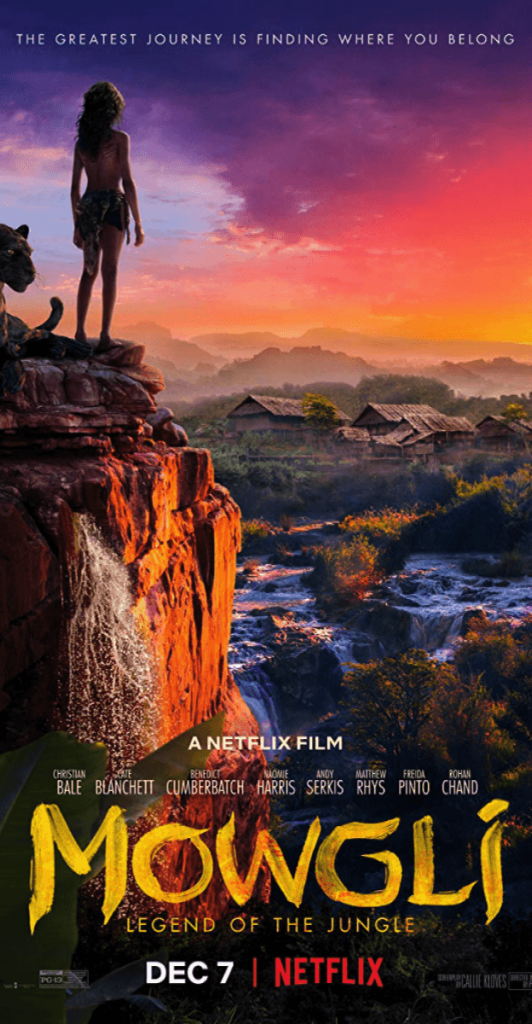

The film ‘Mowgli’ is a recent adaptation by Andy Serkis of the beloved Kipling story ‘The Jungle Book’. It is a fantasy adventure film and a beautifully aesthetic hybrid of live-action, CGI and motion picture that remains true to the original story in its exploration of the darker elements of the tale that follow the man-cub Mowgli in his search for his place within both the Indian jungle and the man-village. Orphaned as an infant by the villainous tiger Shere Khan, Mowgli is rescued by black panther Bagheera and taken to a pack of wolves who raise him and protect him from Khan who wishes to finish what he started. As he grows, Mowgli is forced to confront his human origins and dual identity as tensions between the two worlds mount, to span the bridge between his two domains and bring peace to the jungle once more.

The film’s narrative centres on the duality of animal and human identities, allowing the film to sit comfortably within the fantasy genre, in which ‘the most often reproduced fantasy plot device is that of the protagonist with multiple identities’ [1] which manifests itself as the very crux of this film. Mowgli’s internal struggle with dual identities as wolf and man becomes indicative of the layered dualities in the film regarding the universal struggle between man and his relationship with the animal world. The darker side of the Jungle Book story has always been made more palatable for children in Disney’s recent adaptations. However, by remaining true to the story’s more sinister undertones of the animal/human duality, Mowgli seems a far cry from these previously furry and heart-warming adaptations, and consequently distances itself from its previous status as a family film. Our beloved, comical Baloo is now gruff and brutal, whilst the introduction of colonial hunter Lockwood, Bhoot and his poignant demise constitute the darker, child-unfriendly elements that demonstrate the animal and the human as two sides of the same coin.

Torn identities and the outsider

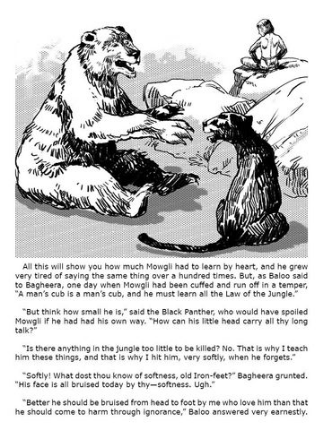

Mowgli’s torn identity lays the foundation for his status as an outsider and he becomes increasingly aware of the differences that distinguish him from the pack when faced with ‘the running’, an initiation undertaken by all young wolves to secure their official place in the pecking order. Mowgli’s inability to keep up with the rest of the wolves during training results in a keen awareness of his own foreignness, but he is not alone.

Bhoot, a small runt albino wolf pup whose own physical differences set him apart as an outsider, mirrors Mowgli’s own narrative to such an extent that he can be seen as an allegory for Mowgli’s own internal conflict. Mowgli and Bhoot’s heart-warming affiliation blurs the boundaries between human and animal by the way in which they become closely associated with the same pain of ostracisation from the family sphere. Both animals and humans can experience the hurt of being an outcast, it is not limited to just one world. This shared emotion and experience reveals some similarities between man and the animal world. We may look physically different from them and so designate ourselves as the outsiders of an animal world in which we can never participate , but we are ultimately more alike than we may think through this shared identity as an outsider. Mowgli’s identities are the genesis of this duality, as he experiences neither belonging fully to the animal world nor to that of man. Serkis’s seamless blend of CGI and motion picture enables these parallels in its creation of animals whose faces uncannily resembles the human actors who play them. The impression this creates ‘is one of animal skulls molded to look more human’ [2] which although appears disturbing, plays not only to our differences from, but also our similarities to the animal world.

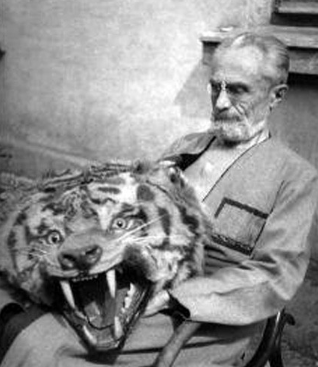

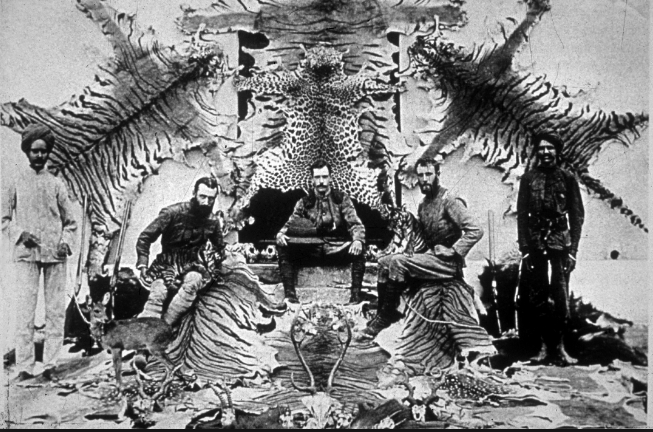

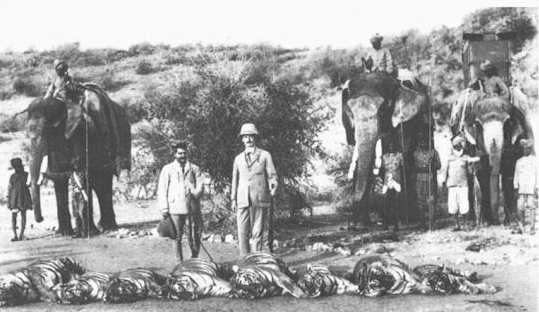

Trophy Hunting and taxidermy

Bhoot’s status as the underdog makes his final demise all the more poignant at the hands of the colonial trophy hunter and taxidermist, Lockwood who is brought into the village to exterminate Shere Khan who has been killing their sacred cattle. His own personal menagerie of taxidermied animals, which include the head of an antelope and a monkey in a glass jar are chanced upon by Mowgli, after having been sent to the man village where he is taken in by Lockwood. During this scene Mowgli encounters most shockingly of all, the head of his beloved friend, a both eerie and upsetting moment. With his white face softly illuminated by candlelight, contrasting sharply with the dark background, he becomes the only thing we see thrust directly into our line of vision, his face set in an unreadable expression torn between an uncanny smile and the beginning of a snarl.

Lockwood’s occupation as a trophy hunter and taxidermy enthusiast plays a significant role with regard to the film’s animal presence in light of Stephen Keller’s affirmation that ‘even the tendency to avoid, reject, and, at times, destroy elements of the natural world can be viewed as an extension of an innate need to relate deeply and intimately with the vast spectrum of life about us’ [4]. Consequently, Lockwood’s killing of animals for sport and trophies can be denotive of a desire for an inaccessible world. The hunter’s penchant for taxidermied animals furthermore, speaks of the complex duality of the relationship between man and animal through the symbolic nature of this art. Taxidermy is a practice that ‘tells us stories about… the loneliness and longing that haunt our strange existence of being both within and yet apart from the animal kingdom.’ [5]

Just as Mowgli is simultaneously within yet apart from the jungle, so are all of us. Taxidermy alludes to this loneliness that we feel in our occupation of this liminal space that finds self-expression in Lockwood’s desire to kill and preserve wild animals. The only part of Bhoot that he chooses to preserve is his head, the most significant part of the animal as it constitutes the ‘essence of the animal’s magnificence and individuality’ [6]. In the animal world Bhoot’s individuality denoted him as ‘the other’ but to Lockwood this uniqueness is something beautiful and ultimately, results in the wolf’s death. As a taxidermied beast in the clutches of man, the animal form and human desire merge to become one, reinforcing the practice as ‘always necessarily marked by and indelibly inscribed with the human longing to perpetuate a particular animal’s beauty, form and presence.’ [7] We assert our power over them by claiming their lives but ultimately their death by our hands is only ever representative of our desire and respect for that animal’s beauty. We are always aware of and similarly bound by our acknowledgement of our separation from the animal world and for some, taxidermy and hunting, fulfils the desire to bridge this separation, to try in a way, however morbid, to become part of the animal kingdom from which we feel so distanced and one that appears so inaccessible to us.

The animal and human hunter

The jungle is a place governed by numerous laws by which all of its inhabitants abide – all except one. During the scene in which Bagheera hunts and kills an antelope to show Mowgli the respected laws of the jungle, he teaches him the most sacred rule of all: never hunt for sport. The dual nature of the hunter is explored in the film in both the animal and jungle worlds. The jungle animals hunt only out of necessity for survival, but Khan breaks this rule and kills man’s sacred cattle not only for his own pleasure but also as a means of asserting control, as Akila says ‘to bring war to the jungle’ [8]. Such an amalgamation of a desire for hunting borne out of pleasure with its use as a tool for control aligns Khan with Lockwood through their shared identity as the hunter that kills for sport, pleasure and power. Moreover, Khan’s manipulative transgression of the jungle’s sacred laws which he exploits to bring chaos and disorder to the jungle, mirrors Lockwood’s presence as the white European in Colonial India. For the jungle animals, the hunt is a sacred act but in the human world, it is a sport. Just as Lockwood uses hunting as a similar means of asserting control over the animal kingdom so too does Khan. Shere Khan does not eat the cattle that he kills but leaves their carcasses strewn across the jungle as a visual reminder and an assertion of his dominance. In this way, Khan identifies more with the human hunter than with the animal hunter, reinforcing the nebulous nature of the human and animal divide through the additional blurring of the boundaries between the two worlds.

Animal presence in Mowgli is fundamentally rooted in the search for one’s true identity. It is, according to Serkis, a film about ‘’learning how to cope with being an outsider… in between two conflicting worlds.’’ [9] Mowgli’s dual identity does not stand alone, but binds us all to the same story, the same inner conflict between the two struggling identities of man and animal. The representation of animals as different, yet ultimately similar to us, through shared identity as an outsider and with a similar desire for power and control facilitates the dual nature of the animal and human within us and the greater, more general distinction between the animal and human worlds. The film’s subversion of the animal/human distinction shows furthermore, that the boundaries between the two are not fixed but appear more as a construct that we have used as a means of distancing ourselves from the animal world in order to cope with our own duality. We have come to accept this construct and so deny ourselves the truth that although different in many ways, we are fundamentally more alike than we may realise. Mowgli’s struggle to find himself acts as a mirror that reflects our own battle to fit into both worlds. Our identity as an outsider of the animal kingdom is moreover tied to a sense of loss and a longing to become part of the animal world. The complexity of this longing as analysed in relation to sports such as trophy hunting and practices like taxidermy that still feature in our society even today, all speak of a complex relationship between man and beast and the inner animal that we keep concealed within ourselves.

Protagonists with numerous identities which they use not only to find peace within themselves but to also unite the worlds of man and animal is also apparent in Disney’s Tarzan (1999). An orphan adopted by an animal family, he struggles with his human and ape identities. In the end, like Mowgli, his acceptance of his dual identities is what unites man and animal and what brings peace to the jungle. In this way, the duality of the relationship between man and animal is not just significant because it speaks both to and about us but also because it shows that peace between the two worlds depends upon it. Mowgli’s final declaration ‘‘I’m not a man! But neither am I a wolf’’ [10] shows that in order to unite the two worlds and our own fractured identities, we must ultimately accept the dual nature of our relationship with the animal world, to accept that we are neither fully man nor are we fully animal and only then can we bridge the gap between the two domains, especially nowadays, where we feel more estranged than ever from the animal world.

Bibliography

Friedman, Lester, An Introduction to film genres, (New York: WW Norton & Co, 2013)

Han, Karen, ‘Netflix’s Mowgli: Legend of the jungle is a strange companion to the Disney version’, Polygon, 2018 https://www.polygon.com/2018/11/28/18116229/mowgli-legend-of-the-jungle-netflix-review [accessed 22 December 2018]

Poliquin, Rachel, The Breathless Zoo, (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012)

Serkis, Andy, dir., Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle (Netflix, 2018)

The Upcoming, Andy Serkis interview on Mowgli at London Premiere, online video recording, YouTube,5 December 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=wVJOpv1W6WA [accessed 20 December 2018]

[1] Lester Friedman and others, An Introduction to film genres, (New York: WW Norton & Co, 2013), p. 160.

[2] Karen Han, ‘Netflix’s Mowgli: Legend of the jungle is a strange companion to the Disney version’, Polygon, 2018 https://www.polygon.com/2018/11/28/18116229/mowgli-legend-of-the-jungle-netflix-review [accessed 22 December 2018].

[3] Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle, dir.by. Andy Serkis (Netflix, 2018).

[4] Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), p.21.

[5] Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), p.24.

[6] Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), p.148.

[7] Rachel Poliquin, The Breathless Zoo, (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), p.149.

[8] Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle, dir.by. Andy Serkis (Netflix, 2018).

[9] The Upcoming, Andy Serkis interview on Mowgli at London Premiere, online video recording, YouTube, 5 December 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=wVJOpv1W6WA [accessed 20 December 2018].

[10] Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle, dir.by. Andy Serkis (Netflix, 2018).