Ever felt like your life was just one long game, and everything to happen was caused by the roll of a dice? No? Well try living 26 years inside Jumanji, a game where all of your psychological fears and anxieties manifest in the shape of wild animals, whether they are excessively oversized mosquitos and spiders, or a stampede of elephants! Joe Johnston’s 1995 action-packed adventure “family film”, Jumanji explores the detrimental effect of repressed emotions and uncovered childhood trauma, whilst at the same time bringing prominence to the growing lack of human control over the animal kingdom.

It’s 1995 and Orphans Judy and Peter Shepard uncover a mysterious board game, hidden for over two decades in the old Parrish house, and as they begin to roll the dice, unleash a world of animal mayhem from the deepest parts of the jungle. When Alan Parish (Robin Williams), a thought to be missing child is released from the game in which he has been imprisoned, he brings with him a world of adventure and trouble, that himself, the Shepard siblings and Sarah Whittle (Bonnie Hunt) must play on to contain. The boundaries between the human world and the animal world are completely distorted, and animals take reign over human control. Monkeys become police officers, and boys become monkeys; the chaos of the animal kingdom, which is presented with different subgroups of species all work together to present the much more sinister undertones, something we might not expect from the adventure family film genre.

The adventure film aids the presentation of animals within the film, as the fast paced, manic nature of the genre itself is mirrored in the animal world. Adhering to the conventions of the genre, Alan and the gang are on a quest, a journey to finish the game he and Sarah started in 1969. However as the quest continues, the tension of each barrier between them and their goal begins to increase, this being presented with the appearance of a stronger, harder to defeat animal each time. The mammal manifestations of Alan’s past psychological traumas, caused by the apparent oedipal father-son rivalry, become the hurdles that the four have to jump in order to resolve the relationship between the Parrish men, and save their town.

The opposition between zoomorphism and anthropomorphism is set up to emphasize the ever growing speed of devolution of the human world to the glorification of mayhem. The dwindling power of human nature is a major theme within the film, thus attributing human qualities or roles onto animals, and vice versa, reinstates the deterioration of mankind.

Early on in the film, Peter and Judy release a pack of CG monkeys, who wreak havoc on the Parrish house, and the town. Despite the early 90s quality of the CG, the monkeys manage to take control of not only cars, but police bikes, even remembering to wear a helmet! Providing monkeys with human skills, such as the ability to drive a motorbike, in contrast with their human counterpart’s evident loss of control, proves an ironic depiction of simians as the superior species. Additionally, placing the monkeys in a role of care and high governance like the police emphasizes further the shortage of human force in the given society.

On the reverse, Peter, as a result of cheating is transformed into a somewhat disturbing half boy half ape, and as his biological clock is reversed. He becomes nothing more than a chimp in a hoodie, nevertheless taking on central characteristics of his monkey exterior.

The zoomorphic depiction of Peter as a simian, something we might associate as being inferior to the human race, stresses the lack of individual autonomy, thus creating an unsettling atmosphere that we as the superior species experience when the control is taken from our hands.

Similarly, Alan is given characteristics of an animal, as he is transformed into the prey of Jumanji’s most feared hunter, Van pelt. Seemingly more obvious as the film continues, Van Pelt is a subconscious manifestation conjured to force Alan to be what his father wanted him to be and have. Played by the same actors as Sam Parrish (Jonathan Hyde), he is the symbol of masculinity, something that as a child Alan lacked. He reverses the conventional roles of hunter-prey and forces Alan to become the latter. Like an animal, Alan has to run and hide from him, presenting constant parallels between Alan and endangered animals. Van Pelt reinstates the fears of the jungle and the notion that everything that has followed Alan are the result from the unresolved issues in his relationship with his father when he shouts ‘stop running and face me like a man‘. Consequently, the game becomes a tool to fix Alan’s reality and what should have been his life.

It becomes increasingly apparent that each animal that emerges from the game is a physical manifestation for a differing emotion or fear that is concealed in Alan’s mind. Starting with bats, the very first animal that is released from the game, who bring with them an overwhelming sense of darkness. Bats, which are regularly associated with gothic malevolence, become the foretellers of the twisted journey that both ourselves as the audience, and the players, are about to embark on. Back in ’69 Sarah was ‘chased down the street’ by a ‘bunch of bats’ who swarmed round her, straight after Alan had been sucked into the game right in front of her eyes, no wonder she’s straight on the phone to her psychologist the moment Alan reappears in her life! Interestingly, Johnston decides to focus in on one particular bat in the scene, who is shown to be clung onto Sarah’s shoulder and almost mimics her own scream, breaking away from the mass of bats. This zoom in distracts the concentration from the colony of bats, and focuses our fear on the species as a whole, rather than the swarm. However, the most disconcerting moment is when we see the bats flood in through the fire place, dominating the color and sound of the scene and overwhelming the room with a high pitch squeal. This shift in control from the human world to the animal world forces us to question how much supposed control we as humans have over the animals in the film. If Sarah is ran out of the house and forced to live a life of terror for the next 26 years caused partly by a group of bats, how can we as humans assume we have the governing roles?

That’s right, we can’t, and the world that Jumanji brings is about to prove to us why.

Soon after, the board reads, ‘Don’t be fooled, it isn’t thunder. Staying put would be a blunder’ and the pièce de résistance of obstacles that the four have to face comes to life.

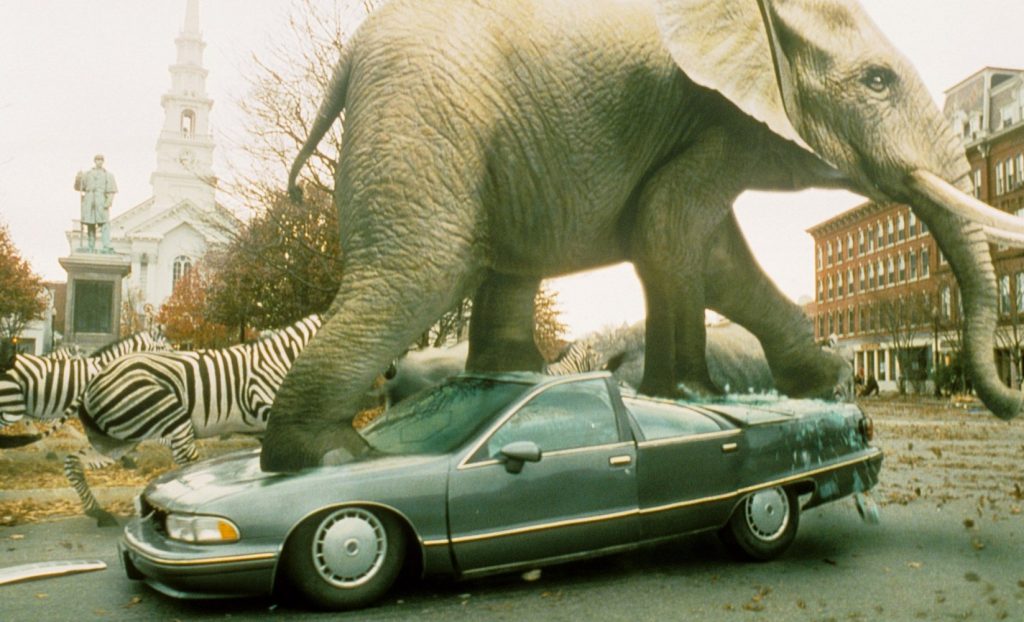

The walls begin to shake, and a stampede of elephants, rhino, zebra and pelicans break through the Parrish library. This scene of chaos and demolition not only creates a somewhat dystopian world, but is also interpreted as the most physical manifestation of Alan’s failed relationship with his father. It doesn’t take an expert to pick up on both the phallic imagery of the elephant’s trunk, and the harsh masculine imagery of the charging rhinos. All of these animals serve to remind the audience of the real puzzle that must be resolved before the chaos of Jumanji can end. Alan’s father persistently encourages him to ‘stand and face’ his fears throughout his childhood, thus it becomes extremely ironic when Robin Williams is quite literally standing face on to a stampede. Johnston’s filming techniques here manage to break the cinematic fourth wall by filming a shot of the animals head on, racing towards the audience, forcing us to face Alan’s problems along side with him. Despite the disconnection between the animals and the landscape, as they don’t normally belong in an urban setting, the techniques used again gives priority to the stampede, forcing the humans to feel as if we have invaded foreign territory, rather than the expected other way round.

As the stampede spreads through the town, shots of elephants walking over cars and zebras racing through the high street project the extent of control animals have gained over humans. Tensions between human intelligence and instinct wildlife become apparent, as the large animals physically crush man made vehicles; metaphorically and physically destroying mans assumed power over the animal kingdom. Cars and technology as such are a symbol for status, intelligence and wealth in the human world, therefore when we see a 10’ foot elephant talking a walk over a bashed up ’96 Chevrolet, we begin to doubt human control.

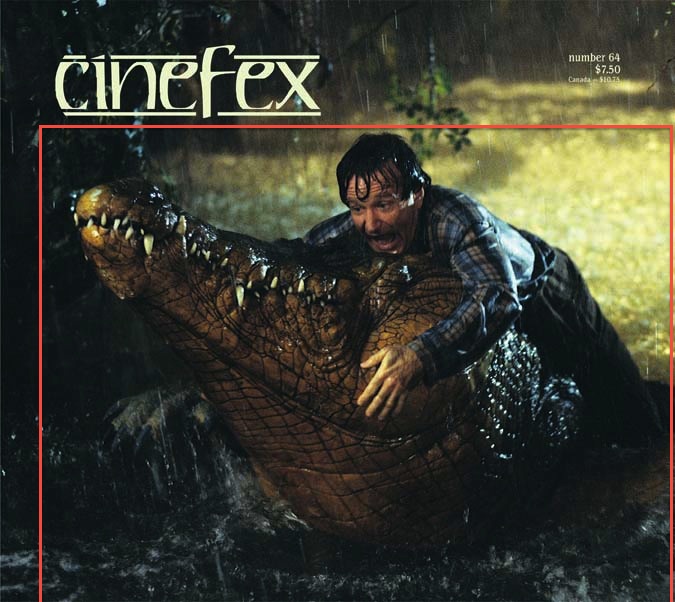

In Alan’s final challenge before the madness is managed, a tsunami begins to flood the house, and with it bringing a 6 foot crocodile. This particular reptile, initially symbolizing primitive instinct, survival and fearlessness, much like the stampede, is a reminder of Alan’s repressed need to ‘man up’ and regain control over his own life decisions. In his own realization of these demands, in an almost Jaws (1975) like fashion, Alan physically launches himself onto the back of the crocodile, and is flung around until finally taken under water with the beast. Alan’s ability to not only face his own fears, but to become the expected male figure is played out throughout this nail biting scene.

Much alike Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) and Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes (1968), the domination and rise of control of the animal world is a majorly prominent theme running throughout. Whether it be an uncontrollable flock of murderous birds, a troop of sophisticated apes, the shift in authority seen in all three films comes across as a satiric message to human kind, a somewhat disturbing threat to our presumed power. So Jumanji not only forces the players and us as the audience to face our wildest fears, but also unlocks a world of madness, waiting to be tamed. The question is, who rolls next?

Filmography

Johnston, Joe., Jumanji (TriStar Pictures, 1996) <https://www.netflix.com/title/660954> [accessed 7 December 2018]

Khan, Ziya, JUMANJI (1995) Behind The Scenes Making Shooting, online video recording, YouTube, 5 September 2017,< https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYwVz9rtIM4>

Bibliography/Further Reading

Altman, Rick, Film/Genre (London:BFI, 1999)

Empire, Empire, 2000,< https://www.empireonline.com/movies/jumanji/review/ > [accessed 27 December 2018]

Grant, Barry K., and J.M.W. “Film Genre: An Updated Bibliography.” Literature /Film Quarterly 10,no. 3 (1982): 188-99 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/43795872>

Lauretis De, Teresa, Freud’s Drive: Psychoanalysis, Literature and Film (Language, Discourse, Society) (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

Shanley, Kathryn W. “Talking to the Animals and Taking out the Trash: The Functions of American Indian Literature.” Wicazo Sa Review14, no. 2 (1999): 32-45.

Film Data

Title: Jumanji

Year of Release: 1996

Director: Joe Johnston

Distributor: TriStar Pictures

Country: United States

Language: English

Does the film contain imaginary animals? No

Kind of Animals: Spider, Mosquito, Lion, Monkey, Alligator, Bat, Horse, Dog, Elephant, Rhinoceros, Zebra, Pelican

Human-Animal Relation: Magic, Hunting, Imaginary, Animal Agency

Major Genres: Action, Adventure, Family