Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit embodies the toxicity of hegemonic masculinity in Nazi Germany, utilising the rabbit ‘as a material and symbolic resource.’[1]. Waititi’s decision to navigate the film through the eyes of ten-year-old Jojo is significant, as Jojo’s own conflicted sense of masculinity is underscored through the rabbit as a symbol of gender, as his character develops alongside the animal.

The rabbit is not immediately visible in the shot, leaving audiences in as much trepidation as Jojo, neither know what he will be tasked with doing in relation to ‘killing’. Using an over-the-shoulder shot, Jojo affectionately cradles the rabbit in a moment of stillness, determining the animal as a material being subject to a ‘creaturely’ gaze – this is crucial in establishing a connection between the human audience as spectator and the animal on screen. Waititi’s choice of camera angle similarly effects the viewer’s interpretation of the relationship between Jojo, Christoph and Hans, exposing a hierarchy of masculinity. Hans and Christoph are clearly placed higher on this hierarchy, being physically older, taller, and more ruthless, contrasting Jojo with little to no emotion towards the rabbit

Figure 2: Jojo being intimidated Christoph and Hans. Jojo Rabbit (2019)

Figure 4: Jojo holding the rabbit. Jojo Rabbit (2019)

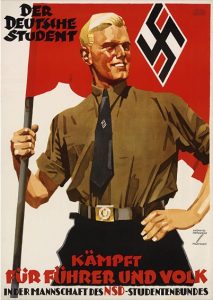

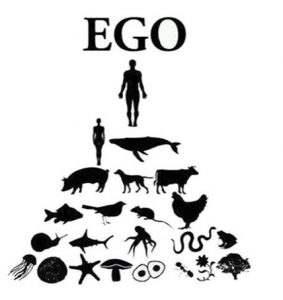

This contrast emphasises the vulnerability of the rabbit, as it becomes an object of entertainment value, exploited for its subservience and role in reaffirming an ‘anthropocentric ethos’: the principle that humans are the centre of everything. Here, this idea is reinforced more specifically through the patriarchal masculinity of Nazism, with this ideology centring on the notion that all Nazis (particularly Nazi men) have claim to a superiority over all beings. In this world, animals like the rabbit, viewed as weak and passive, (and humans with similar dispositions like Jojo) will struggle to thrive and, ultimately, survive.

The stillness of this moment is interrupted when Christoph instructs Jojo to kill the rabbit, followed by a burst of non-diegetic orchestral music. The unexpected introduction of sound stresses Jojo’s reaction, with the staccato mimicking his struggle to comprehend the instruction. As the music continues to build, the camera turns to zoom on Jojo, effectively building the tension, as the attention of the viewer is focused solely on Jojo, allowing them to understand the emotions evoked in him by the rabbit and the pressures he is facing, whilst gaining insight into his struggle between natural and performed masculinity. In this moment, when both Jojo and the audience look at the rabbit, what they see most clearly, is JoJo himself, exemplifying his vulnerable position as a boy with empathy and sensitivity within the dominating circle of the Hitler Youth.

Waititi, here, comments on how patriarchal ideologies reinforces speciesism: under patriarchal Nazi ideology, anything (human and non-human) other than the superior German race doesn’t deserve moral consideration in the same way as the untouchable Nazi human. This belief is the result of the ideological fallacy of human supremacy, more specifically within the film, the result of Nazi patriarchal supremacy – adhering to the belief that there exists something essential in humans that allows them more moral value than other living beings. This belief underpins the structural violence seen in this scene, the way in which non-human animals are exploited, mistreated, and oppressed as a result of a larger political ideology. Building on this, the scene culminates with Jojo unsuccessfully trying to free the rabbit, as Hans snaps its neck. This action is a crucial demonstration of speciesism in motion, as all moral value of the rabbit is removed through Christoph and Hans’ actions, with this moment critiquing human culture’s failure to understand that the vulnerability of animals should be valued, and not to justify murder for pleasure.

Figure 6: Jojo setting the rabbit free. Jojo Rabbit (2019)

Returning to an over-the-shoulder shot, Waititi concentrates on Jojo’s reaction. The rabbit acts as a foil for Jojo, with its cuteness reflecting that of Jojo and aiding viewers to recognise Jojo’s more typically feminine traits: being vulnerable and sensitive. Thus, as the rabbit is killed, Jojo’s authentic self is similarly crushed, as his actions result in the death of the rabbit despite his best intentions. The superficial nature of masculinity here becomes clear, as this scene exemplifies how it is not a fixed feature of male bodies, but ‘a social construction of a masculine self-enacted in front of an audience.’[2]As a typically feminine, harmless animal, the rabbit is easy to assert control over, consequently becoming a tool for the older boys to convincingly perform masculinity before an audience. This failure to correctly perform masculinity and fulfil hegemonic ideals establishes the nickname, ‘Jojo Rabbit’, as the characteristics of the rabbit drift into the characterisation of Jojo, with ideas of the rabbit and what it represents drifting into both his peers’ and the audience’s idea of him and the realities of his character. With this, the discourse of species becomes subtly intertwined with the film and the animal becomes central to its narrative.

However, the idea of the rabbit as a feminine, harmless animal is later subverted when Jojo’s imaginary friend and hero, Adolf Hitler tells Jojo ‘The humble bunny can outwit all of his enemies. He’s brave and sneaky and strong. Be the rabbit’.[3] This speech exposes the temporality of patriarchal ideology in reinforcing hegemonic masculinity, as the symbol of the rabbit is completely flipped, becoming representative of traits that are all desirably masculine and encouraging Jojo that he still embodies the characteristics of the ideal Nazi. Waititi’s appearance as Hitler in this moment is significant here, demonstrating how even the most superior of humans in the eyes of Nazi patriarchy is able to view an animal as small as the rabbit as an animal that is wise, cunning and somewhat invincible – giving the film, and Jojo’s nickname an entirely new meaning.

Bibliography

Christian W., Lippert “Snake Mind, Wolf Body, Panther Courage: Jojo Rabbit as a Critique of Hegemonic Masculinity” (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Utah State University, 2021) in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8096 ,<https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8096 > [accessed 11th November 2021]

Shukin, Nicole, Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009)

Creed, Barbara, ‘Animal Deaths on Screen: Film and Ethics’, Relations, 2.2.1 (2014), 15–31

Malamud, Randy. “Animals on film: the ethics of the human gaze.” Spring, 83, (2010) 1-26

[1] Shukin, Nicole, Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), p. 6.

[2] Christian W., Lippert “Snake Mind, Wolf Body, Panther Courage: Jojo Rabbit as a Critique of Hegemonic Masculinity” (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Utah State University, 2021) p.13, in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8096, <https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8096 > [accessed 11th November 2021]

[3] Jojo Rabbit, dir. By Taika Waititi (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2019) <https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/video/detail/B084QJ5QZB/ref=atv_yv_hom_c_unkc_1_1> [accessed 10th November 2021].