For as much as this film teaches us about the meaning of Christmas, it equally teaches us about the relation humans hold with animals, through both interaction and perception. The protagonist, The Grinch, lives in a cave at the top of Mount Crumpit with his dog Max, after running away from his adopted home in Whoville as a child one Christmas. The Grinch is regarded as Other by the townsfolk, aligning his wild animal-like appearance and unhygienic lifestyle with his mean actions towards the town’s annual Christmas celebrations. He is denounced by the town residents as smelly, hairy and cruel, creating a rhetoric that the sinister traits of his character are those connected with animality.

‘Slithered and slunk with a smile most unpleasant, around each Who-home and he took every present’

Most importantly to the plot, he is considered ‘Grinchy’, an adjective created by the town, meaning lacking in Christmas spirit. Christmas is the most revered holiday of the townspeople, and through The Grinch’s non-celebration, turned attempted ruin, of Christmas, he has been outcast from Whoville and its community for many years. The crux of the film, as suggested by the title, is The Grinch’s plot to steal all of the town’s Christmas gifts and decorations in order to ruin the festive period. Although him are Max are successful in this, he learns that Christmas is about more than just gifts, and undergoes a drastic physical and metaphorical change of heart, as he restores the town’s possessions at the conclusion of the film. It is The Grinch’s relationship with Max that ultimately gains The Grinch his anti-hero status, as, along with Cindy Lou, he teaches The Grinch to take back his wrong-doings and stop his heart from being ‘two sizes too small’.

A live-action family/fantasy film, How The Grinch Stole Christmas (2000) is the blockbuster adaptation of Dr Suess’ rhyming children’s book How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957). The film shares key thematic elements of the original story, in its poetic narration and costume and hair design.

Furthermore, all of the films formal elements – its visual, literary and sound design – work to construct a perception of The Grinch as an animal in comparison to the Whos. The town builds a rhetoric that he is less of a Who and ‘more of a what’. This works to build a barrier between the two social types, that The Grinch’s anti-hero epiphany breaks at the conclusion of the film, proving you can leave your past behind you, no matter ‘Who’ you are.

The Grinch’s visual design components aid his negative perception. Jim Carrey, who played The Grinch, spent three hours before each day of filming getting into costume, prosthesis and makeup. The costume itself was made of Yak hair, dyed green and then individually sewn into the spandex suit (Robinson 2002).

The prosthesis placed onto Carrey’s face covered most of his face including his cheeks, nose, and forehead, in order to create the character’s iconic wrinkly skin texture. Alongside green and yellow eye contacts, and lack of clothing throughout most of the film, these costuming choices create an image of The Grinch as more wild animal than a Who.

It is not only The Grinch’s appearance that exacerbates his animal qualities, but the shot sequencing choices. In the very first shot of The Grinch within the film there is a close up of his hairy, green face messily eating a raw onion. In the following shot he uses the same half eaten onion as deodorant for his armpits. This sets up imagery of unhuman and unhygienic characteristics from the outset of the film.

The setting plays a part in this imagery, as his home is the dumpsite of all of Whoville’s rubbish. He is often pictured within the trash, positioning him as literally being at home with the rubbish that was thrown away from Whoville just as he was. When he takes the ‘dump it to Crumpit’ rubbish chute back home, he rejoices in receiving more of the town’s trash, remarking ‘ooh goody another load!’ ‘What is that stench? It’s fantastic!’ It is the combination of visual design and dialogue here that allow the audience to recognise he is not only feral, but happy living this way. These visual design elements are often largely influenced by comedic value, feeding into the genre of family film through its slapstick moments. In one scene, The Grinch removes his dirt-ridden socks, before they become alive, squeal, and run away.

Within the films narrative, The Grinch uses the perception of him as untamed to his advantage, manipulating it in a way that the Who’s are repulsed by him enough to leave him alone. We see this in a scene where he burps on a shop keeper in order to stop harassing him to buy Christmas products. CGI is used to create the visual effect of a large cloud of green smoke blown from The Grinch’s mouth, along with a burp sound effect.

This combination of visual design elements allows a connection to be made between The Grinch’s wild animal characteristics and the people of Whoville’s bad perception of him. The mayor of Whoville, Augustus May Who, comments that ‘he had hair, not pleasant. He shed, not right’ when Cindy asks about his memories of The Grinch. This assigns The Grinch’s animal-like features to the perception of him as a bad person, connecting being green with being mean, and not welcome as a citizen of Whoville. This is reflected in the first digital adaptation of the story, a 1966 CBS television special. The Grinch goes from a menacing hairy animal to a cute blue-eyed lover of Christmas. This not only demonstrates that the negative traits of The Grinch’s character are linked directly to animality, but in fact those connected with moral integrity are linked to humanity.

Through this notion, duality is created in The Grinch’s character, the bad animal and the good Who. The Grinch’s actions, regardless of them being positive or negative, cruel or thoughtful, are directed by his emotions, proving he had always possessed more humanistic tendencies than he would like to admit. His human characteristics take the most obvious form in his treatment of Max, viewing him not as an animal counterpart but as a household pet.

‘Dogs usefully are the easiest way to define their owners… what animal has played more roles on both sides of the spectrum, both heroic and villainous?’

Chodosh (2018)

Throughout, Max, as many cinematic animals in the genre are, is used for comedic value, usually at The Grinch’s expense. In the Post Office scene, Max bites The Grinch’s rear, alluded to by a loud biting sound effect before we see as much. This elicits him to shout at Max: ‘that is not a chew toy’, ‘get that out of your mouth’ and ‘you have no idea where that’s been’, played over a fast motion shot of the pair spinning around.

Here, a comedic irony is developed through the dialogue, through our schema of pet keeping, as we connect the comments with those that we would use with misbehaving pet dogs. The same schema is used repeatedly in other dialogue-based comedy, such as ‘get the stick… there’s no stick, I’m smarter than you’ and ‘Max, fetch me my sedative!’ Then when The Grinch returns from the Holiday Cheer Meister celebrations to find Max dancing on his hind legs to Christmas songs, he throws him outside in the snow.

This mimics the idea of keeping dogs outside at night if they misbehave, portrayed through physical comedy. These links to pet keeping are consistently exemplified through the pair’s interactions, something that binds the narrative, especially in The Grinch’s eventual change of character.

Max holds the position of both animal and man’s best friend, allowing him to persuade The Grinch to listen to Cindy and make better ethical decisions. Arguably, he can do this because ‘dogs are more ingrained in human society than arguably any other animal…more connected to humans than any other animal’ which is often represented in family film culture (ibid). Although Max is inferior to The Grinch, through the manipulation of sound design, using only dog sound effects for Max’s ‘dialogue’, because they have a relationship of pet and owner, The Grinch endlessly trusts him.

As is witnessed in the Post Office scene, it is Max’s interception that persuades The Grinch to pull Cindy out of the sorting machine. Further into the film, when Cindy hands The Grinch an invitation to attend the Cheer Meister celebrations, Max uses growls and barks, known dog behaviours, to communicate his feelings. He whimpers when The Grinch is negative about the invitation, and again when Cindy gets sent home through the rubbish chute. Within the scene, Max’s whines are edited in a way that illustrate him pleading with The Grinch to attend the celebration. Finally, when The Grinch is still indecisive on the matter, Max pulls the cord to send him down the chute down to Whoville, deciding for him, whether he wants to attend or not. Max is seen to facilitate The Grinch’s actions towards positive change in his life, something that is particularly recognisable in the penultimate scene from the film.

From the very top of Mount Crumpit, The Grinch realises Christmas hasn’t been ruined as he thought it would, and begins to understand the true meaning of Christmas, his heart starts to grow. As Max watches on and sees him confused and in pain, he becomes worries for his owner, whimpering. Once The Grinch has recovered, he tells Max he loves him, and for the first time throughout the film we see Max’s tail wag, a trait we associated with dog’s happiness. He then runs over to The Grinch, and licks his face, regarded by the audience as a way of dog’s showing affection and appreciation to their owner. The lighting turns golden as this happens, to represent the happy ambiance as The Grinch heart grows.

The Grinch must then save Cindy from falling down Mount Crumpit, as Max barks to cheer him on to pull the sleigh harder, jumping on his hinds legs in celebration when he succeeds. Max continuously wishes the best for his owner, supporting him in both his evil pursuits and good endeavours, showing that pet keeping forms a sense of loyalty between animal and owner that cannot be matched.

The final scene of the film returns to, and subverts, the elements of visual design we are set up with from the beginning of the film. We are presented with a two shot, with a close up of Cindy and The Grinch. Cindy kisses him on the cheek, and remarks ‘your cheek’s so…’, to which he replies, ‘I know, hairy’. The Grinch is so determined that the negative perception of him will never go away that he doesn’t believe anyone could view him as anything more. Cindy replies ‘no’, to which The Grinch then guesses it must instead be ‘greasy? Stinky? Do I have a zit?’, when in fact his cheek is ‘warm’. This is the final confirmation we receive of his character development, transforming from the wild animalistic outcast, to the ‘warm’ Who, who restored Christmas to the town.

How the Grinch Stole Christmas is a film interested in perceptions of immorality and their connection to animals. The perception of The Grinch changes and progresses throughout the film, but the perception of wild animals does not. He is considered more human by the conclusion of the film, rather than the same animal with a new positive attitude. His positive perception is enabled through another animal, Max, through the connection the pair share because of pet-keeping. Max encourages him to change in a way that moulds to the Who’s society, as an animal teaches an animal how to be more human.

Ron, Howard, dir., How the Grinch Stole Christmas, (Universal Pictures, 2000)

Bibliography –

Chodosh, Caleb (2018) “Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema,” Momentum: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/4

Robinson, Lizzie, The Fact Site, 2022 <https://www.thefactsite.com/facts-about-the-grinch/#:~:text=Jim%20Carrey%20spent%20total%20of,to%20get%20into%20the%20suit> [accessed 17th January 2023]

Figures –

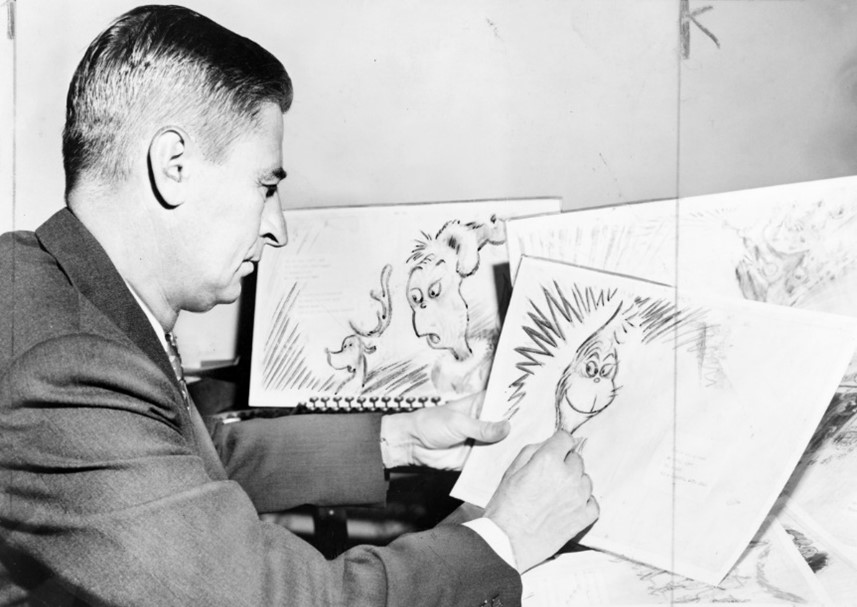

Figure 2: Universal History ArchiveUIG, Dr Suess Drawing the Grinch, photograph of Dr Suess illustrating the Grinch, Biography, 7th November 2018 <https://www.biography.com/news/dr-seuss-grinch-inspiration> [accessed 18th January 2023]

Figure 4, 6 and 7 : Yoe MJ, “El Grinch’ (“How the Grinch Stole Christmas”) Maquillaje, Still photograph captured from video & video, Youtube, 16th December 2013 < <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=009wPQyVM7c> [accessed 18th January 2023]

Figure 5: Thompson, Avery, Jim Carrey Played The Grinch, Side by Side comparison of Jim Carrey in and out of costume, Hollywood Life, 22nd December 2021 <https://hollywoodlife.com/feature/how-the-grinch-stole-christmas-cast-then-and-now-photos-4277538/> [accessed 17th January 2023]

Figure 9 and 10: Zimmerman, Leona, How The Grinch Stole Christmas, Still photograph captured from video, dailymotion, 19th November 2016 <https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x52pql5> [accessed 13th January 2023]

Further Reading

Chodosh, Caleb (2018) “Good Boy: Canine Representation in Cinema,” Momentum: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/4

James Serpell, In the Company of Animals: A Study of Human– Animal Relationships (Cambridge, 1996 )

McLean, Adrienne L., Cinematic Canines : Dogs and Their Work in the Fiction Film (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2014)

Ratelle, Amy, Animality and Children’s Literature and Film, 1st edition. (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

SkyScape (2022) How the CIA trained Jim Carrey to endure the Grinch, SKYSCAPE. Available at: https://spyscape.com/article/jim-carrey-trained-with-a-cia-torture-expert-to-play-grinch