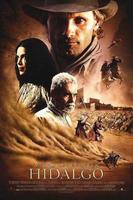

Hidalgo (2004), directed by Joe Johnston is a Disney production bringing to life the adventures of America’s most controversial endurance rider; Frank T. Hopkins. His story was discovered and then written for the big screen by John Fusco, a strong advocate for the veritable nature of his incredibly controversial legend. A whole website has been devoted to denounce Hopkins’s claims of his countless victories on horseback. The film is based in 1890, on the writings of Hopkins that document his participation in the deadly 3,000 mile race across the Arabian Desert, dubbed the ‘Ocean of Fire’. Hopkins became the first outsider to participate in this prestigious race, in which he challenged purebred Arabian horses, the only horse with a pure bloodline, to compete against his mixed heritage Spanish mustang and his western ways. The film journeys through his personal struggles, both physical and emotional, throughout this heroic feat. The trailer for the film covers several of the issues raised in this post- it even features the tag line ‘based on a true story’ which has been the source of outrage and controversy.

The most enduring and flexible of genres.

The western is one of the oldest American genres, and one that has been adapted greatly throughout its time. [1]Hidalgo takes the form of a revisionist western due to its sympathetic disposition towards the Native American community, epitomised by the protagonist’s inextricable links to both communities thanks to his dual heritage. The revisionist western came about in the 1960s as a response to the classic western and explores the previous justifications of violence inherent in this genre[2].

Westerns are commonly concerned with the struggle of humanity against nature, with civilisation against the wilderness and the battle between virtue and evil.[3] The archetypal conflict remains but the presence of the Arab community replaces the previously vilified Native Americans. The film was released during period of much animosity between America and the Middle East, just a year following America’s invasion on Iraq. As Philip French identifies, a common trope of the western genre is that, ‘the tales [are] as much about the hopes and anxieties of the time in which they were made as the period they were set[4].’In this context- the film produced in the midst of the post-9/11 Bush Administration- the display of domination of the West in the East takes on new meaning ‘as the epic struggle between savagery and civilisation become a useful shorthand and explanation for American forays in the Middle East[5]’. Conflict between the two differing ideologies sparks through the medium of horse racing, coded as a battle between ideologies, faith and power, and culminates in a presentation of western technological superiority. The most central aspect to this western is the presence and complicated purpose of the faithful steed, the mustang stallion Hidalgo.

‘Mustangs don’t belong in races with thoroughbreds.’

The horses in Hidalgo very much steal the show in relation to animal presences and representations. Although other animals are present, they serve as a more contextual basis to develop the scene.

Hidalgo, a mustang, is used as a vehicle throughout the film to explore various different cultural issues. Firstly, and most predominant is the issue of identity. This issue of liberty and freedom is inextricably linked with that of identity and selfhood. The free-roaming horse of the American West is cast aside and considered unworthy by many on the grounds that he is of ‘impure’ origin. This parallels Hopkins own angst over his biracial identity; his mother the daughter of a Sioux Chief and his father a white cavalry scout. Chief Eagle horn approaches his qualms most explicitly with the words,

‘I call you Far Rider, not because of your great races and your fine pony, but because you are one who rides far from himself, and wishes not to look home. Until you do, you are neither white man nor Indian, you are lost.’

Hidalgo, therefore, is portrayed as a method of escapism- the notion of the internally troubled outsider being a common trope in the Western. Nearing the end of the race, as Hidalgo lies wounded and exhausted upon the ground there is a high angle, longshot of a desperate Hopkins crying out to his Lakota ancestors. From the angle of the shot (shown below) Hopkins adopts a remarkable physical likeness to a Sioux.

Directly following the scene Hopkins discards his Western comforts and rides bareback in the native fashion. He demonstrates this significant shift in his perception of self-hood solely by riding upon his horse. The use of animals permits these astounding subtleties that speak volumes; allowing Frank T. Hopkins to silently but confidently embrace his ancestry.

The term ‘Mustang’ is a derived from the Spanish word ‘mestengo’ meaning stray, untamed and wild. The relationship between Hidalgo and Hopkins is not one of domination but one founded on mutual respect, Hopkins maintains that Hidalgo is not tamed (demonstrated through his various humoristic displays of personality) and therefore an interplay between the domestic and the wild is introduced. Characteristics associated with the traditionally stoic American cowboy are also adopted by his trusty steed. Much is made in the film of portraying Hidalgo as an entity separate from the control of Hopkins; it is Hidalgo that bucks off a drunken Hopkins and parades him around a show arena and it is Hidalgo that assumes the authority to continue with the race despite his possibly life-threatening injuries. With such an unmistakable display of character, the audience root for the mustang just as previous audiences supported the stoic cowboy. Thus the directors effectively capture and channel the emotions surrounding the plucky pinto ‘pony express’, to bolster support for the United States.

Frank Hopkins frequently refers to Hidalgo as ‘brother’ and ‘partner’ and it is the horsemanship that draws a line between those perceived to be the virtuous and those considered the villains, dictating perceptions upon both character and culture. Native Americans, according to Hopkins, refer to horses as ‘big dogs’ due to their loyal disposition and count the horses as sacred animals. The Arabs also consider horses as sacred, but on the grounds of the purity of their blood, having been in the words of Sheikh Riyadh, ‘sculpted by the essence of Allah[6]’.Therefore they are aligned with having a more ruthless attitude to their horses, their relationship more one of transport, of personal glory, than of companionship and equality. When the first sacred horse fell just miles from the starting line the rider stabbed him through the heart, conveying the concept that the horse is bred for one reason only; to win. The preservation of the Arab bloodline in the horses is considered integral to their breeding and seemingly also to the Islamic religion. Something that Joe Johnston seems to be well aware of, ‘Hidalgo was allowed to breed with the purebred Arab mare, because he had won this race. To someone who holds the purity of the Arabian equestrian bloodline almost as religion, that’s like blasphemy.’[7] There is therefore a subtle battle grounded in religious ideology.Equine perfection is pitted against the mustang, and the struggle is one between identity dictated by blood and by religion, against identity of being and of mind.

The mustang presents the extremes of these problems, bringing to the forefront the immorality of a blind pursuit of purity that almost everyone in the film is culpable for. The White American is guilty of attempting to eradicate the mustang, ‘if you ask me they [mustangs] belong in fertilizer’ and the Arabs are guilty of maintaining a pure, ‘untainted’ blood line that does not allow for diversity. With herds of wild mustangs being gradually slaughtered in the background, the race is portrayed as an act of defiance to those in the pursuit of what is effectively a utopia bound for failure. The victory of Hidalgo demonstrates that there is nothing superior to a harmonious combination of cultures. Their victory can be seen as a celebration of the multiculturalism within the United States of America, the nation that is heralded as the ‘Mother of Exiles’. Hopkins can simultaneously be indigenous and American; Cowboy and Indian; US victor over the Arabs while culturally sensitive friend to the Sheikh; masculinist man and feminist ally to women[8]. The final scenes of Hopkins and Hidalgo’s success cement this message as the white man embraces his identity, the flag of his native people in hand , whilst championed as ‘Cowboy!’ by the chanting Arabs clustered along the shoreline.

The success of Hidalgo is acknowledged by the Prince in his grudging praise, ‘It is a magnificent horse’; giving rise to the idea that nature breeds better than even the best man made manuals. This in turn also recasts the American nation with all of its diversity and complexity as a force to be reckoned with on the international stage.[9] Kollin’s identification of America’s victory having political connotations is incredibly prevalent to the period that the film was released into; a time in which the invasion of Iraq had begun just a year previously and showed little sign of ceasing in the near future. Interestingly, placing the finish line on the shore of Iraq raises questions concerning the objectives of the film. Iraq as the name of a particular country dates only to the end of the World War One. As this horse race is based in the 18th Century , the country does not yet exist. Additionally the relationship between Sheikh Riyadh and Hopkins sheds more light on this perception. The friendship forged between them can read as an acceptance, even an approval, of the American presence in the region. The name Riyadh also references the capital of Saudi Arabia, a country that proffered support to the US during their involvement in Iraq[10]. Therefore Kollin draws attention to the victory of America in the Middle East as a very real show of western superiority.

‘Let her buck’

The film brings to the forefront the legend of Hopkins, and whether based on truth or legend, the direct impact upon the mustang is undeniable.[11] The film transcends beyond screenplay, and impacts the way that humanity approaches the wild horse in much the same way as occurred in The Misfits. This activism is vital as today more mustangs live in government holdings than in the wild.[12] Viggo Mortenson actually bought the horse that played Hidalgo, a stallion by the name of T.J who according to Mortenson was ‘a right character.’[13]

‘The horse of a most unusual colour’ has several representations throughout the course of the film; he approaches the issue of multiculturalism, plays with the concept of liberty and draws into question our concept of individuality. Integral to the film, is this issue of identity. Hidalgo demonstrates the importance of self most prominently through his own breeding, he is not a pure-bred horse but is the result of a diverse society (paralleling the multiculturalism present in the United States of America). Therefore their victory is both a personal triumph and yet also a triumph over the so called ‘purity’ of blood.

In having his trusty steed as a mustang there is a constant dialogue between liberty, nature and humanity; the concept of gentling the wild. The emancipation of the mustangs at the end of the film is very cathartic for the viewer, evoking a sigh of relief at the sight of the herd breaking the confinements of the corral. Hopkins turning Hidalgo loose epitomises this scene, demonstrating nature and humanity as an entity rather than an opposition. Their freedom also speaks of a new American attitude. As a revisionist western, Native Americans are no longer demonised but instead are allowed a position at the heart of America; portrayed through Hopkins’s embracing his dual heritage. A link is forged at the outset of the film between the mustangs and the Indians, both having been disappearing in concert due to military action. By turning the mustangs loose, the film expresses America’s guilt and sadness, however its regret is relegated to a past that cannot be changed- even through symbolic gestures. Instead militarism and violence is redirected to ‘liberate’ new countries, and the mustang’s freedom can be read as an emancipation of an oppressed people, the Arabs.

On a similar note.

Whilst exploring the legend of Hopkins, I discovered a rich selection of films that champion the continued freedom of the mustang. Among these films of varying genres are; ‘Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron’ and ‘The Misfits’ andalso include a couple of documentaries; ‘Running Free; The Life of Dayton O. Hyde’ and ‘Wild Horse, Wild Ride’. Each documentary presents a ‘solution’ to the continued threat upon the freedom of the mustang. The former presents the founding of sanctuary for the wild horses, and the latter reveals a competition in Texas that attempts to break 100 mustangs in 100 days in order to sell on the newly ‘tamed’ animals for adoption. The concept of domesticating a wild animal is also approached in, ‘Born Free’, a film in which Joy and George Adamson care for a baby lion until her adulthood before releasing her back to into the wild. In both Hidalgo and Born Free the actors invested deeply in the cause for the animals featured in the film, personally championing their protection.

[1]Tim,Dirks. Westerns Films, American Movie Classic Company,(no date) <https://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html>, [Accessed 23 November 2013] (para.1)

[2] The Script Lab, Western, Genre, (2010) <https://thescriptlab.com/screenplay/genre/western> [Accessed 22 November 2013] (para.4)

[3] Ibid (1) < https://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html> (para.4)

[4] Susan Kollin, ‘‘Remember you’re the good guy’: Hidalgo, American Identity, and Histories of the Western’, American Studies, 51:1/2 (2010) Project MUSE < https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_studies/v051/51.1-2.kollin.html> [accessed: 28/12/2013] (p.6)

[5] Susan Kollin, ‘‘Remember you’re the good guy’: Hidalgo, American Identity, and Histories of the Western’, American Studies, 51:1/2 (2010) < https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_studies/v051/51.1-2.kollin.html> [accessed: 28/12/2013] (p.10)

[6] Hidalgo, Dir. Joe Johnston. Disney/ Touchstone Pictures. 2004 [Film]

[7]The Guild, The Long Riders’ Guild, ‘The Truth about Mustangs versus Arabian Horses’, The Hidalgo Hoax (no date) <https://www.thelongridersguild.com/mustangs.htm> [accessed: 02/01/2014] (para. 9)

[8] Sturgeon, Noel, Environmentalism in Popular Culture: Gender, Race, Sexuality and the Politics of the Natural, (USA: The University of Arizona Press, 2009) (p.74)

[9] Susan Kollin, ‘‘Remember you’re the good guy’: Hidalgo, American Identity, and Histories of the Western’, American Studies, 51:1/2 (2010) <https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_studies/v051/51.1-2.kollin.html> [accessed: 28/12/2013] (p.17)

[10] Susan Kollin, ‘‘Remember you’re the good guy’: Hidalgo, American Identity, and Histories of the Western’, American Studies, 51:1/2 (2010) Project MUSE (p.19) <https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_studies/v051/51.1-2.kollin.html> [accessed: 28/12/2013]

[11] The Horse of the Americas Registry and IRAM, Frank T. Hopkins, (2003), <www.frankhopkins.com > [Accessed 22 November 2013]

[12] Fawn DeSiree, Capturing Wild Horses, YouTube (June 2013) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6aTfsnFUyVI > [Accessed: 26 November 2013]

[13] Tt, Waco, Viggo Interview-Hidalgo, YouTube (March 2006), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmQxYecHZmE > [Accessed 24 November 2013]

BIBLIOGRAPHY/ Further Reading

All photos taken from the DVD version of Hidalgo, Touchstone Pictures, released in 2004.

Hidalgo, Dir. Joe Johnston. Disney/ Touchstone Pictures. 2004 [Film]

Tim,Dirks. Westerns Films, American Movie Classic Company,(no date) <https://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html>, [Accessed 23 November 2013]

The Script Lab, Western, Genre, (2010) <https://thescriptlab.com/screenplay/genre/western> [Accessed 22 November 2013]

Susan Kollin, ‘‘Remember you’re the good guy’: Hidalgo, American Identity, and Histories of the Western’, American Studies, 51:1/2 (2010) Project MUSE <https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_studies/v051/51.1-2.kollin.html> [accessed: 28/12/2013]

The Guild, The Long Riders’ Guild, ‘The Truth about Mustangs versus Arabian Horses’, The Hidalgo Hoax (no date) <https://www.thelongridersguild.com/mustangs.htm> [accessed: 02/01/2014] (a very rich source with several links to other articles and archives)

Sturgeon, Noel, Environmentalism in Popular Culture: Gender, Race, Sexuality and the Politics of the Natural, (USA: The University of Arizona Press, 2009)

The Horse of the Americas Registry and IRAM, Frank T. Hopkins, (2003), <www.frankhopkins.com > [Accessed 22 November 2013] (another source very wealthy in links to various other articles)

Fawn DeSiree, Capturing Wild Horses, YouTube, (June 2013) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6aTfsnFUyVI > [Accessed: 26 November 2013]

Tt, Waco, Viggo Interview-Hidalgo, YouTube (March 2006), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmQxYecHZmE > [Accessed 24 November 2013]

Anthony Amaral, Hidalgo and Frank Hopkins, Horses in History, Western Horseman Magazine (1969)< https://www.horsetimesegypt.com/pdf/articles/HISTORY/Horses_in_History_Hidalgo_&_Frank_Hopkins.pdf > pp48-50 [accessed: 26/11/2013]

John, Fusco. Open letter from John Fusco, (no date) <https://www.horseoftheamericas.com/uploads/3/1/3/7/3137829/johnfusco.pdf> [Accessed 18 November 2013]

Shaheen, Jack, Guilty: Hollywood’s Verdict on Arabs After 9/11 (Massachusetts: Olive Branch Press, 2008)