James Gunn’s superhero trilogy focuses on the Guardians of the Galaxy, a gang of misfits teaming together to save worlds, whilst morally bettering themselves and learning to grow from their trauma from criminals into heroes. For the trilogy’s final instalment, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3[1], Gunn focused on the origin of Rocket, a violent, intelligent raccoon whose background has always been a dark mystery. The little information concerning his past came from the first movie, in which we saw the horrific scars on his back, and his tearful anger as he bitterly stated, “I didn’t ask to be torn apart and put back together, over and over [and] turned into some little monster[2].” Rocket also refuses to acknowledge or accept that he is a raccoon, often becoming violently unhinged whenever it is inferred. Though this disillusion is typically comedic, it does force an audience to wonder why Rocket is so resistant to accepting his race and what happened in his past to create this violent rejection of self. By manipulating the uncertain dread, the viewer feels towards Rocket’s origin, Gunn creates a more emotionally mature and compelling adventure, that is not only a fitting end for the heroes, but subsequently raises awareness about the mindless brutality of animal experimentation. This blunt depiction of animal cruelty is jarring due to its abnormality from the sci-fi superhero genre and makes the moments of unjust torture we see more striking, as we are accustomed to funnier, lighter stories from similarly themed and styled blockbusters. Gunn’s choice to have Rocket being the centre of this abuse is exceptional as witnessing a comic relief character go through extreme trauma is a brilliant way to capture the attention and sympathy of the audience and by inflicting danger onto a weak, cute creature, fearful discomfort is created whenever the kit is on screen.

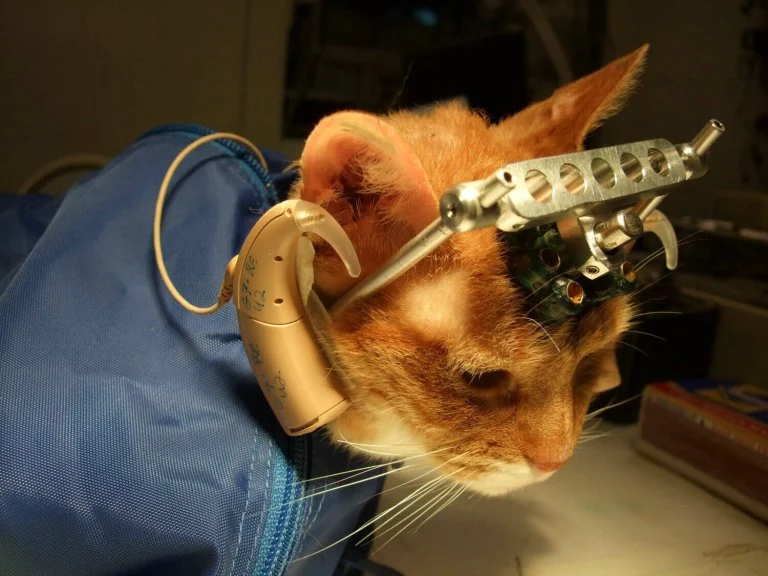

In the opening scenes of the film, Rocket is put into a coma, struggling to stay alive. This separates the film into the Guardians trying to save his life whilst stopping those trying to destroy him, and Rocket’s mind as he flashes through the trauma inflicted upon him as a kit. By dedicating a large proportion of the film to detailing the torturous creation of the abnormal creature, the viewer is unable to avoid the shocking and ruthless imagery presented and is subsequently forced to experience the extreme reality, much like Rocket as his mind runs him through the trauma he has been avoiding his entire life. Gunn displays the horror of the situation immediately, as the first flashback reveals an infant rocket directly after surgery being roughly tossed into “batch 89”. The kit is vastly unlike the Rocket we are familiar with due to, not only its small size but its severe fragility. It struggles to stand due to its clear physical agony and its body is covered in robotic enhancements and bleeding scars, most prominently of which is around its head, displaying the brutal ways in which they tampered and experimented on the infant’s brain. As the kit shudders in fear and anguish, it is approached by the creatures of Batch 89, which, like Rocket, were genetically enhanced animals that look inhumanely created. As each animal approaches from the shadows, the viewer and the kit become rightfully wary as their physical appearances are disfigured and freakishly abnormal, with the walrus’ eyes being bloodshot and mechanically held open whilst the rabbit has arachnid-like legs and a sharp metal jaw. This involuntarily initial terror of the creatures is quickly manipulated by Gunn when it is revealed that these creatures are compassionate and caring rather than the monsters we believe them to be. Gunn is demonstrating how horrific the results of animal experimentation can be as experiments can turn innocent animals into horrific, mutilated beasts. This realisation of their jovial nature is apparent once they start attempting to comfort the shaking kit and become quiet and sympathetic once the infant shakily manages to croak “hurts.” By having Rocket’s first words be one depicting its agony, the audience is distraught at how their beloved hero is only able to describe its pain as an infant. By having a very humanistic response to pain and fear, or seeing someone suffer, Gunn’s beliefs about animal testing become clear as these creatures seemingly have more morality and humanity than those who created them and left them to rot inside dirty, bone-ridden cages.

The relationship between the genetically enhanced creatures is beautiful yet unnerving to the viewer. The animals are frequently seen having a jovial time, playing games, and having talks about their roles and wishes for the “new world” that has been promised to them by their creator, the High Evolutionary. Though the closeness of the animals is heartwarming, the audience is never unaware of the looming dark truth that this story cannot end happily due to these merely being memories Rocket refuses to accept. As Lylla, Floor or Teefs have never been seen thus far into the franchise, the viewer is wary of their upcoming fate and fearful of what could’ve happened to traumatise Rocket into becoming a criminal. The dread is amplified when the animals discuss the names they would like to be called once in the new world. They dreamily lie in their cages, staring up at the ceiling dreaming about their lives and breathlessly imagining what they could be called, giggling about the unoriginality of some of their names. This conversation is highly reminiscent of conversations children would have, reflecting on where they would like to be when they grow up, yet it creates severe remorse within a viewer, as their dreams are already an impossibility due to their setting, as they dream about traversing the stars whilst locked in an unclean, darkly lit cage. The overhead shot should be beautiful with the characters lying next to each other, smiling into the sky with angelic non-diegetic music, yet in reality there is no sky and just an artificially lit prison that they have been born into and realistically have little chance to escape from. This futile dreaming is heartbreaking and reflects Gunn’s celebrated voice throughout the film, as he was praised for ‘suggesting that just because we can experiment on them doesn’t mean that we should[3].’ By creating these characters that have child-like mentalities and aspirations, and then submitting them to an extreme variation of animal experimentation, the viewer is forced to question the ethics of animal testing and how moral it truly is.

When concerning those who conduct animal experimentation, Vaughan Mooney argued that “Opponents of animal experimentation may argue that such a scientist simply has ceased to feel [whilst] the scientists will argue that their work is of sufficient importance to the community at large to outweigh their feelings[4].” This idea of a character who’s numb to the suffering of others whilst pursuing a “perfection,” is vivid through the Chukwudi Iwuji’s High Evolutionary, Rocket’s creator and the villain of the final Guardians of the Galaxy film. The High Evolutionary is a mad scientist, believing that his “sacred duty is to create the perfect society,” and as a result, his perspective on life is critical and flawed. Any fault in a being results in it being unsuitable, even when the said being can “survive on 30 calories a day,” “an hours sleep a week,” and is constantly “happy.” He is striving for a perfection that doesn’t exist and is repulsed by lower lifeforms, such as Rocket or his friends. This lack of remorse is cemented once the Guardians arrive on Counter-Earth, a planet he created full of genetically modified anthropomorphic beings. Despite the God-like status, he maintains over this world (seen most comically through the recreated Statue of Liberty in his image), he remorselessly destroys it due to his civilian’s petty crime and imperfections, claiming he will “start again.” Through the High Evolutionary’s callous nature, the audience can perceive Gunn’s negative opinions about those responsible for animal experimentation, and their clear carelessness with life, especially when considering that most “experiments are often driven by curiosity and serve no real purpose[5].”

In the final act of the film, the High Evolutionary states “There is no God, that’s why I had to step in,” emphasising the god complex that is key to both his character and Gunn’s presentation of animal experimentation. The villain’s self-perceived superiority fuels his cruelty towards lower lifeforms, and he believes it is his right to disfigure and manipulate animal bodies, to achieve some unspecified goal. The animals we fall in love with and follow for most of the film are merely “a melody of mistakes they could learn from” to help “the creatures that truly mattered.” Despite the close connection the audience has formed with Batch 89, to their creator, they are nothing but an experiment to see how they could improve those they believed had a purpose. This reveal is devastating as not only does Rocket realise the paradise, he dreamed about was never meant for him, but the audience discovers how flawed and cruel animal testing is. By cruelly breeding and experimenting on animals to discover trivial facts that may or may not benefit humanity, there is a direct parallel between the deranged supervillain and real-life scientists that ‘can prevent species-typical behaviours, causing distress and abnormal behaviours among animals[6],’ through animal testing.

Though Gunn demonstrates the brutal consequences of animal experimentation and the vileness of those who willingly torture creatures, he also displays what perspective an individual should strive for through the other Guardians of the Galaxy and their quest to save Rocket. Despite the tensions of the first films, in which the Guardians mocked Rocket, calling him “trash panda[7]” or “vermin,” the Guardians reveal their powerful love for their friend by immediately leaving their haven to steal lifesaving information from the secure ‘OrgoCorp.’ The lack of hesitation to put themselves into danger to save an animal typically associated with aggression and disease with a common belief being that the “best raccoon is one squashed and flattened on the road[8],” is noble and reveals how deeply they care for a commonly unwanted creature. This unwavering care for animals is further demonstrated later in the film when the Guardians discover what the High Evolutionary did to Rocket. Despite denying violence as an option, they are quick to break their “kill no people” rule once discovering the extent to which Rocket was tortured. This leads them to “kill them all” with little remorse as they are blinded by their hatred of the monsters who would be willing and morally capable to commit such ethical atrocities. Their rush to violence forces an audience to feel excitement as they get revenge on those responsible for hurting and killing the innocent creatures they had fallen in love with. Impressionable audiences will be enthralled by their heroes and happy to mirror their beliefs, choosing to despise and stand against those willing to cause harm to animals, revealing how Gunn has not only taught audiences who the real-life villains are but also how all life is sacred and should be protected from those willing to do it unnecessary harm.

Gunn unveiled that, for him, “Rocket is the secret protagonist of the Guardians of the Galaxy and has always been the center of it[9]” which is profound when considering the final moments of the film. When helping the children on board the ship to escape, Rocket accidentally finds the room in which he was raised. In the dismal room, he sees the cage from his earliest memory and opens it to find many other kits whilst slowly reading that he is a raccoon, tearing up at the revelation as he attempts to pick up every Raccoon he can. Instead of running away from his trauma, Rocket is confronting his past and accepting who he truly is, not only by saving any animal he can but by calling himself “Rocket Raccoon” to the High Evolutionary, embracing proudly what he is, despite being raised to resent it. By having the protagonist of the film accept himself as a species held in negative regard and common within animal experimentation, Gunn is exclaiming the injustice of animal testing, as it destroys creatures such as Rocket, and utilises people who choose to view such animals as numbers on a spreadsheet, rather than an actual living being.

[1] Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3, dir, by James Gunn (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2023).

[2] Guardians of the Galaxy, dir. by James Gunn (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2014).

[3] Colley, Moria, ‘James Gunn Nets PETA Award for Spotlighting Animal Testing Cruelty in ‘Guardians’’, Peta (2023) <https://www.peta.org/media/news-releases/james-gunn-nets-peta-award-for-spotlighting-animal-testing-cruelty-in-guardians/>.

[4] Monamy, Vaughan, Animal Experimentation: A Guide to the Issues (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[5] Harp, Rachel, ‘‘Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3’ Has a Powerful Message About Animal Testing’, Peta (2023) <https://www.peta.org/blog/guardians-of-the-galaxy-vol-3/>.

[6] Akhtar, Aysha, ‘The Flaws and Human Harms of Animal Experimentation’, Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 24 (2015), 407–19 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0963180115000079>

[7] Guardians of the Galaxy Vol.2, dir. by James Gunn (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2017)

[8] Corman, Lauren, ‘Getting Their Hands Dirty: Raccoons, Freegans, and Urban “Trash”’, Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Vol. 9 (2011).

[9] Chin, Daniel, ‘In the End, Rocket Raccoon is the Star of ‘Guardians of the Galaxy’’, The Ringer (2023) <https://www.theringer.com/marvel-cinematic-universe/2023/5/8/23715659/guardians-of-the-galaxy-vol-3-rocket-raccoon-marvel-cinematic-universe>

[10] Disney Plus

[11] Peta

[12] The Bug Master