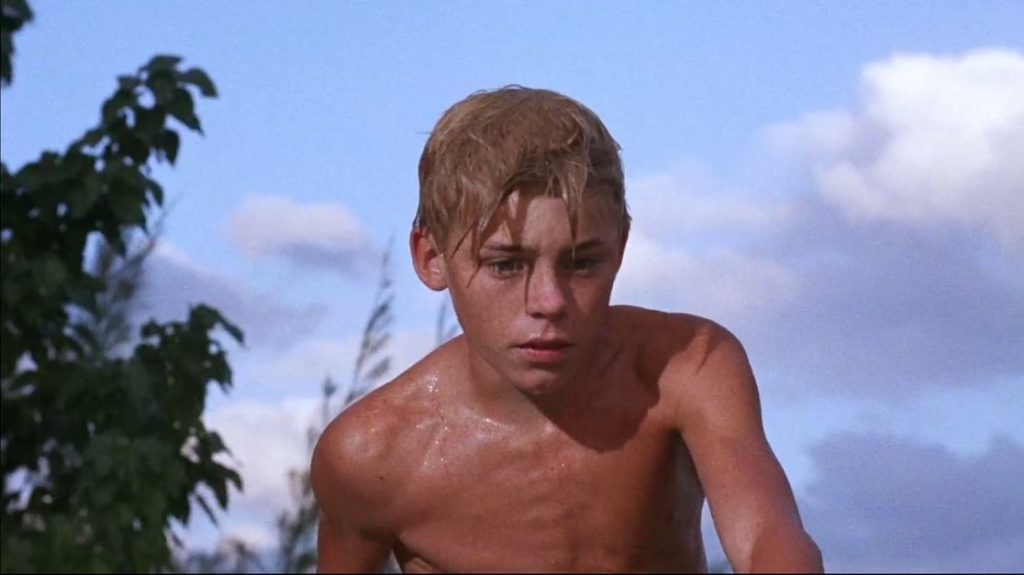

Flipper is a family film from the 1960s that centres on one fateful summer when 12 year old Sandy has an extraordinary experience with a dolphin. Sandy enjoys helping his father with the family fishing business but unfortunately a disease called the red plague is killing off all of the fish; when their town is hit by Hurricane Hazel it seems like times will be hard for Sandy’s family. One day while out snorkelling Sandy sees his friend Kim’s cousin hit a dolphin with a harpoon and Sandy brings the dolphin home to try and save it. Sandy names the dolphin Flipper and fortunately he recovers, bonding with Sandy through learning tricks. However Sandy is devastated because he must release Flipper once he is healed and fears he will never see him again, but in a twist later in the film Flipper returns the favour by saving Sandy after he is attacked by a shark.

The main genre of Flipper is family film; this genre is associated with ‘any Hollywood film whose plot, characters, and style are intended to appeal to children under the age of approximately twelve years’[1]. Flipper fits within the family film genre because of its simple plotline which only has a couple of minor sub-plots, main characters including a young boy and his parents, and a simple overall style which supports the developments on screen. The plot of Flipper weaves a gentle tale about a boy and his dolphin with only minor sub-plots that do not detract from the main storyline, there are a few moments of mild danger but this film was classed as a ‘G’ rating or ‘General Audiences’ which is described by the Motion Picture Association of America as ‘Nothing that would offend parents for viewing by children’[2] which places Flipper firmly into the family film genre. The main characters and are also the ultimate embodiment of the non-offensive as Sandy lives with his mum who is a homemaker and his hardworking dad who are the epitome of the ideal 1960’s family. This film’s style also fits neatly into the family film genre as straightforward musical cues are used to let the audience know that the scene is about to change, which are also combined with several montage scenes that don’t really advance the narrative but allow the audience to watch a pleasant segment where a boy has fun with his pet dolphin.

There are several important moments involving animal presence in Flipper but the moment which directs the rest of the narrative is when Sandy sees a dolphin get speared by a harpoon, and this scene is key in relation to the representation of animals in the film because of its presentation of Flipper before he is associated with Sandy. This scene is the most distressing in the whole film for several reasons, firstly in the sequence before Flipper is harpooned Sandy and Kim are in a period of equilibrium[3] which is reflected in the bright lighting and the upbeat non-diegetic sound of woodwind. This equilibrium lures the audience into a false sense of security which disappears when the music changes down an octave and two consecutive shots are shown which juxtapose the harpoon and the dolphin, this combination suggests to the viewer that a disequilibrium is approaching. The second that the dolphin is speared he emits a high pitched squealing sound that can only be interpreted by the audience as screams of pain, however afterwards the cousin who shot the dolphin is given no reprimand by Kim’s father and it is only Sandy who is concerned enough about the dolphin to go and help it. Before Sandy goes to help the dolphin he says ‘my father taught me to put… any animal out of its pain, especially a dolphin because they beach themselves before they die.’ Therefore at this point in the narrative Flipper is still basically just another animal to Sandy.

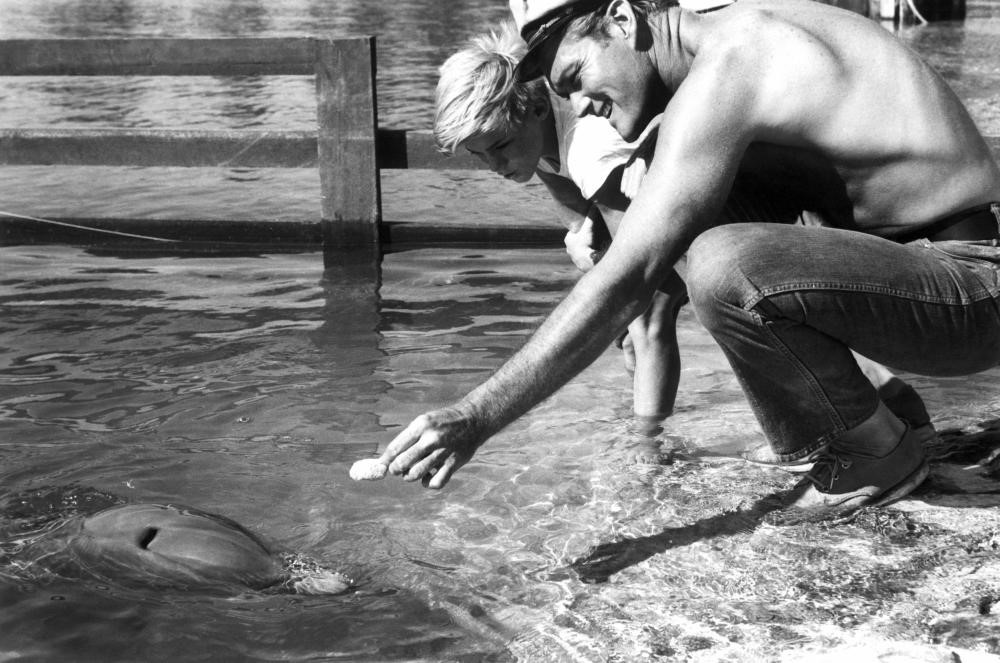

A second important moment in the representation of animals in Flipper is when Sandy bonds with the dolphin and realises that Flipper is more intelligent than other sea animals; there are several cinematic devices which support this shift in perception. Slapstick comedy is used to support the bond between the two main characters when Flipper makes Sandy jump, knocking Sandy into the water; slapstick is used as it is a form of comedy easily recognised by children, reinforcing the family film genre style. The music here is playful and the sequence where Sandy falls in is followed by a shot of Flipper ‘laughing’ at him, this anthropomorphism is the beginning of the dolphin’s development from animal to friend. This development continues through a non-verbal conversation between Sandy and Flipper with the use of alternating mid-shots of each character, similar to those used in a more conventional conversation sequence in order to create a sense of connection between boy and dolphin. This stage of getting to know each other also signifies that Flipper falls into the family film sub-genre of buddy film which features ‘protagonists who mature through a close friendship with an equal’[4] Sandy matures through his relationship with Flipper as he comes to realise the value of the life he has saved, and this comes to a climax in a third key animal moment when Sandy is forced to release Flipper back into the sea. However Flipper also falls into the sub-genre of rite-of-passage film which ‘promote maturity through adult mentorship’[5] as Sandy is forced to release Flipper by his father because he hasn’t completed the work he was set.

The theme of maturity is reinforced by the mentorship that Sandy is given by his father when he talks to him about loss and Sandy is able to understand the way his father feels after losing a friend because he has lost his friend Flipper. Flipper further assists the promotion of Sandy’s maturity when he helps to find fish for Sandy’s father, despite Flipper later returning to eat the fish that Sandy caught this event still helps Sandy to mature because it leads to his father lecturing him about adult responsibilities such as providing for a family. In this way the two sub-genres become intertwined as both Flipper and Sandy’s father help Sandy to develop his maturity. However Flipper also helps Sandy’s father to develop his understanding of the value of life in the final key moment of animal presence where Sandy is saved from sharks by Flipper. Similar to earlier scenes deeper sounding music is juxtaposed with shots of sharks to foreshadow the events in order to help a younger audience understand the events that are unfolding. Suddenly Flipper cuts into a montage of short shots and fast cuts to have an action packed fight with several sharks to save Sandy, which is witnessed by Sandy’s father who was just about to shoot dolphins in the fight for fish, and this teaches him to share the ocean with them instead.

In general the representation of animals in Flipper is divided between adults and children as they are only represented as having value when they either produce an emotional response in a child or are proved useful to an adult. When Sandy first meets Flipper in the film he is fully prepared to do what he has been taught he should do by an adult and takes his gun to put this injured animal out of its misery, however on seeing Flipper and lacking the emotional maturity to kill an animal his emotions force him to try and save the dolphin instead. This emotional response is developed further as his bond with the captive dolphin builds and by the end of the film Flipper has become a friend. Conversely, Sandy’s father has no qualms about taking his gun out to kill dolphins even after seeing his son save and befriend one until Flipper saves Sandy from the sharks and proves his usefulness to him. The adult response in this film takes on additional meaning when compared with the life of Ricou Browning, who is the author of the novel on which the film was based. Browning was inspired to write the novel after he ‘went to the amazon, captured freshwater dolphin, brought them back to Silver Spring [a water park] and put them in the water there.’[6] Therefore even the author of the novel about setting a dolphin free viewed these animals as a commodity to be captured and used.

A comparison which struck me consistently while watching Flipper was the 2013 documentary Blackfish which explores the issue of Killer Whales in captivity in an American water park called SeaWorld. After watching Blackfish I have never been able to watch a film about animals in captivity in the same way again and find myself constantly questioning the ethics behind training wild animals. Flipper questions the concept of keeping dolphins in captivity in a much more basic way than Blackfish questions Killer Whale captivity, but this is only to be expected when comparing a children’s film from the 1960s with a documentary. However there are still certain ethical aspects of Flipper that are troubling despite its simple nature, for example neither of Sandy’s parents tell him that a dolphin shouldn’t be kept as a pet in a tiny pen when he asks to keep Flipper, they only say things like ‘how are you going to feed it?’.

[1] Wheeler W. Dixon, Film Genre 2000: New Critical Essays, (New York: State University of New York Press, 2000), p.178.

[2] Motion Picture Association of America Film Ratings [online]. 2016 [cited 24 January 2016] Available from: <www.mpaa.org/film-ratings/>

[3] Dorothy J. Hale, The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory 1900-2000, (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford: 2006), p. 191.

[4] Wheeler W. Dixon, Film Genre 2000: New Critical Essays, (New York: State University of New York Press, 2000), p.186.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tom Weaver, Double Feature Creature Attack, (McFarland, 2003), p.106.