Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. Dir. Matt Reeves. 20thCentury Fox. 2014

‘Now, they may have got their hands on some of our guns. But that does not make them men. They are animals!’ – Dreyfus

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) is the second film in the 20thCentury Fox reboot of the Planet of the Apes series. The movie is set in 2026, ten years after the event of Rise of The Planet of The Apes and the outbreak of the ALZ-113 virus which virtually wiped out the human race but allowed for the cognitive evolution of ape species. This destabilises the significance of evolution in defining human and animal relations in the film because it removes the idea of human exceptionalism, instead placing both human and ape on an almost equal evolutionary platform to represent two opposing communities with equal capability to destroy each other.

The plot follows Caesar; a genetically enhanced chimpanzee (played by Andy Serkis) who has established himself as the leader of a self-sufficient simian community in the woods just outside of the fallen San Francisco. Caesar and his followers believe that humanity has all but died out until they run into a small group of survivors lead by the film’s human protagonist Malcolm (played by Jason Clarke) who are hoping to use a hydro-electric dam near Caesar’s colony in order to restore power for their own community. After a series of cold standoffs between the humans and apes, the two groups decide to peacefully coexist for a short time under the promise that the humans will leave the simian community alone after they restore their power. This fragile peace agreement is threatened from both sides when Caesar’s lieutenant Koba (played by Toby Kebbell) shoots Caesar with an automatic weapon and leads the apes to war against the humans, after learning that the leader of the human community; Dreyfus (played by Gary Oldman) has been stockpiling weaponry to use against the apes.

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is a science fiction film set in a post-apocalyptic world in which the ‘Novum’[1](a term used by Darko Suvin) or organising logic of the film’s world is that the airborne ALZ-113 virus that killed off most of humanity, also allowed for the evolution of the simian species when exposed to it. As mentioned before, the apes are evolved, therefore they cannot be labeled as entirely animal, which disrupts the human vs animal binary in regard to the conflicts that arise between the two species. This is furthered by the fact that no actual apes were used in the making of the film. Instead of human vs ape, the film explores the dangers of the us versus them mindset between any evolved species. Within this film, the apes symbolise a community whose ideology is based on the idea of isolationism [i] which is in direct contrast to the human community and their quest to ‘rebuild and reclaim the world’. In doing so Reeves strays away from the classic good vs evil trope to drive the plot of the film, instead presenting the audience with an allegory that explores the nature of war and what motivates two sides capable of mutual destruction to seek to destroy one another.

Reeves uses the characters of Koba and Dreyfus as dual figures to explore the dangers of the us versus them mindset. Koba hates humanity because of his backstory in Rise of the Planet of the Apes in which he was as a lab chimp suffering various scientific experimentations. Throughout Dawn the audience learn that Koba ‘only learned hate’ from humans which is why he advocates that the apes should ‘destroy the humans while they are weak’. This mirrors Dreyfus’ language regarding the apes when states that he wants to ‘kill every last one of them’. Both of these characters use language that is steeped in violence and destruction as they come to represent individuals that allow their hatred of the opposing side to blind them from the positive message of co-operation that the film is trying to make. Reeves makes the audience dissociate with both characters through scenes that show both characters willingly sacrifice their own species without remorse in order to destroy the other.

One of the most shocking scenes of the film that cements Koba as a ruthless antagonist comes about 1 hour and 30 mins into the film where Koba murders another ape named Ash when he refuses to kill two human civilians. In the scene, Koba grabs Ash by the back of the neck and drags him up a flight of stairs as the audience listen to Ash’s distressed screeching. The lack of all other background sound in this scene draws the audiences focus towards Ash’s distress and fear of Koba in this moment. As Ash is thrown over the banister, the camera cuts to a shot from below that shows Ash falling to his death, before the audience hear a thud signalling his body hitting the ground. This scene is pivotal in the film because it shows that Koba is no longer ‘fighting for ape’ as he claims but rather ‘fighting human’ at the cost of his own society. This is reinforced in the final confrontation of the film in which Caesar states ‘Koba fighting for Koba’ after Koba turns his weapon on the apes around him. Koba’s hatred becomes an allegory for the toxic effects that prejudice for the other can lead to the destruction of one’s own community.

Similarly, Dreyfus’ prejudice and hatred for the ape community is motivated by the death of his family due to the simian flu. This is evident when he scrolls through pictures of his family on an iPad. A blackened and chipped part of the iPad screen aligns with Dreyfus’ chest in the picture as if over his heart. This shows the way in which the death of his family has blackened and poisoned Dreyfus’ heart to know only hate and mistrust like Koba. Dreyfus blames the apes for the death of his family, when in reality the simian flu was ‘developed by scientists in a lab’. Dreyfus refuses to acknowledge this fact, instead seeing the ape as the enemy to the point where he is also willing to sacrifice his own people in order to destroy the apes. Dreyfus’ hate progresses throughout the film in exactly the same way as Koba’s. Towards the end of the film, Dreyfus kills himself and the people around him by setting off an explosive device in order to destroy the tower that he knows the apes occupy. Like Koba who says justifies his actions by saying he is ‘fighting for ape’ Dreyfus’s last words are that he is ‘saving humanity’.

In this way the film displays both characters as being motivated to war by a misguided hatred for the other species. Dreyfus’ broken and scarred interior is represented literally in Koba through his exterior scars. Both characters have suffered throughout their lives, but what links them together is their choice to blame the other species for that suffering. The fact that both characters take on the antagonist role within their communities shows that the film is taking a moral stance against the blame game mindset that they both represent.

David Desser argues that ‘science fiction films [are a] valuable tool for cultural analysis [and that] the themes… of such films in any given era may be held as an index of the dominant political and ideological concerns of the culture.’[1]When looking at the film through a geo-political lens, the focus that Reeves is directing the audience towards is in seeking to destroy other community, Koba and Dreyfus brought about not only their own destruction, but also the death of the people they were trying to protect. The fact that the film does not end on a happy or peaceful resolution, but with the escalation of the conflict between the two species serves as a warning against policies that seek to guarantee security through destruction and war. According to Eric Greene ‘the success of the [Planet of the Apes] franchise lies in its practice of adopting conflicts of the time [intensifying] and [escalating] them, and

to imagine their successful resolution’[2]. While this quote is in relation to the original franchise, it is arguably still relevant. By using the science fiction genre, Reeves is able to explore the concept of war and mutually assured destruction through the safe space of the already post-apocalyptic world.

The film conforms to genre expectations through the use of special effects. According to Forbes magazine the budget for digital effects was ‘somewhere in the neighbourhood of $60-80+ million’[1]. Which are used to reinforce the species ambiguity of the ape characters. The apes that we see on screen are in fact human actors that were trained by the likes of Terry Notary and WETA’s Dan Lemmon to use technology such as arm extension devices, Motion capture and CGI in order to transform from this…

To this…

You can watch motion choreographer Terry Notary demonstrate some of the techniques that were used by the actors on screen in order to act out the role of the ape characters. https://youtu.be/3fJhZSwoCVQ

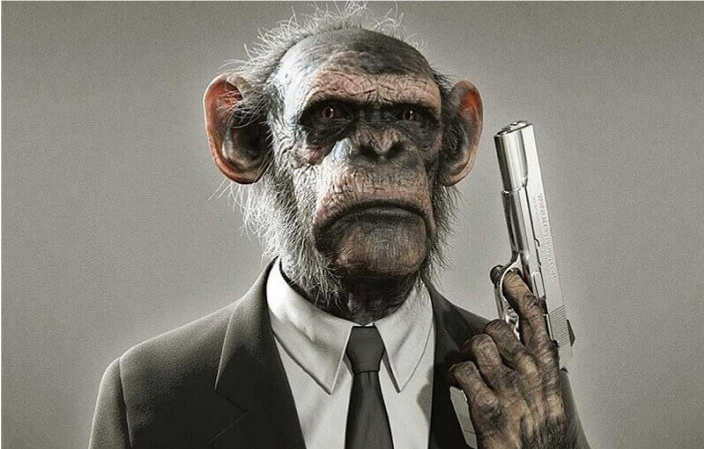

What’s interesting is that the actors are not ‘acting like apes’[1]but as characters that occupy neither human nor animal territory. This provides for some interesting characterisations in the film as species no longer forms the basis for character development. According to Catherine Shoard in an article titled ‘What monkeys mean in the movies’ apes are sometimes stereotyped into the role of what she calls ‘the homicidal heart’[2]which sees ape characters represented as mindless killers. In contrast, Dawn resists this generalisation, Koba is no more a mindless killer than Dreyfus, neither is he bad because he is an ape, just like Dreyfus is not bad because he is human. Even if the film ultimately condemns them, both characters have well developed and convincing motivations for their behaviour. Each side of the conflict has its protagonists that advocate for peace and mutual respect, but at the same time, both sides have antagonists that strive for war and destruction. It is character actions that define them. We as an audience associate equally with Malcolm and Caesar even though they are on opposite sides of the species divide because of positive qualities such as friendship and co-operation that they exhibit in their behaviour, just as we dissociate with Koba and Dreyfus because of their aggressive behaviours. In this way, the film spreads out self-identity not on the basis of species, but on the basis of behaviour.

The conclusion that the film comes to is that inward looking mindsets that seek to destroy what they don’t understand are unsustainable and dangerous in an age of technological advancement. In this way the film ends on the escalation of the conflict between the two groups instead of a peaceful resolution, to show the ease in which society can degenerate into conflict even amidst the good intentions of a few individuals.

a policy of remaining apart from the affairs or interests of other groups, especially the political affairs of other countries.[3]

Further reading

https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/9715/1/sciencefictionalaesthetics.pdf

https://www.animalsandsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/baker.pdf

Bibliography

Greene, Eric, and Richard Slotkin, “Planet of The Apes” As American Myth ([Middletown Conn.]: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1998)

Hughes, Mark, “How ‘Dawn of The Planet of The Apes’ Turned Actors into Apes”, Forbes.Com, 2019 <https://www.forbes.com/sites/markhughes/2014/11/19/how-dawn-of-the-planet-of-the-apes-turned-actors-into-apes/#131226c82fa6> [Accessed 9 January 2019]

“Isolationism | Definition of Isolationism in English By Oxford Dictionaries”, Oxford Dictionaries | English, 2018 https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/isolationism [Accessed 30 December 2018].

Kerman, Judith, Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott’s “”Blade Runner”” and Philip K. Dick’s “”Do Android’s Dream of Electric Sheep? ([Erscheinungsort nicht ermittelbar]: Bowling Green University Popular Press, US, 2003), p. 110.

Kincaid, Paul. “Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 22, no. 2 (82), 2011, pp. 277–281. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24353188.

Shoard, Catherine, “What Monkeys Mean in The Movies”, The Guardian, 2011 https://www.theguardian.com/film/2011/aug/03/monkeys-in-the-movies [Accessed 6 January 2019]