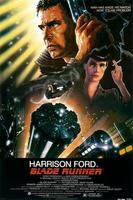

Dystopian L.A. 2019

Blade Runner (1982) takes place in a futuristic and dystopian Los Angeles. Heavy industrialisation has caused great damage to Earth’s atmosphere and ecosystem, wiping out most of the planet’s animal species. ‘Replicants’, androids visually identical to humans, are engineered to perform manual work on off-world colonies. Their use is banned on Earth, where police units called ‘Blade Runners’ hunt down and execute Replicants that break the ban; a process called ‘retirement’. The narrative follows Rick Deckard, a retired Blade Runner coerced into retiring a murderous group of Replicants seeking asylum. Animals too are genetically engineered to be indistinguishable from their real-life – and rare – counterparts. Attitude towards animals is integral to identifying Replicants. Suspects are subjected to an empathy test (called a ‘Voight-Kampff’) that monitors heart rate and eye movement when a scenario is posed regarding cruelty to animals; the responses are used to measure a subject’s empathy levels towards the animals suffering. If the answers show a lack of emotion, they are branded a Replicant and retired.

Blade Runner is primarily a science-fiction film; however it also invokes a number of generic tropes from film noir. The setting and technologies are distinctly futuristic, for example the robotics of the Replicants, and flying cars. The narrative lends itself to the gloomy and cynical tone of noir, as highlighted by the solitary Deckard in a depressive and visually-dark city.

‘Science-fiction is a literature set in worlds different from our own – and different in ways that invite the reader to interrogate these differences.’

Sci-fi may be described simply as:

- An imaginative construct of a universe that deals with advanced technology, beyond anything plausible within the real world. This universe can be either utopian or dystopian.

- A medium to examine the implications of using/abusing this technology and, frequently, implications of human manipulation of Nature.

‘Sordid or strange, death always emerges at the end of a tortuous journey. Film noir is a film of death.’

A scene from film noir ‘The Big Combo’

Film noir can typically be identified by:

- Black and white film, with heavy use of shadows and smoke adding mystery to the scene; characters (particularly women); and to the story.

- Isolated, ‘hard-boiled’ male detectives who tackle crime on their own. Frequently, the narrative revolves around violent crimes, ranging from robbery to murder.

Animals in Blade Runner are not a constant presence; nor are they integral to the plot. They are extremely significant however in their role as facilitators for critiquing humanity, and in successfully distinguishing man from machine. Imitation animals exist as an alternative for the Earth’s near-extinct fauna, and these creations are used to emphasise the consequences of technological growth. Here the sci-fi genre is at its most prevalent; showing us futuristic tech that has grown at an exceeding rate. Subsequently, the audience is posed the open-ended question of whether such growth is morally acceptable. That is, the film uses the loss of living animals to highlight the potential dangers of human creativity: technology can be advanced, but it may come at the price of infringing on Nature’s designs. In one scene Deckard enters an animal market. Displaying no signs of shock or admiration, he walks through a menagerie of exotic animals including ostriches, camels, and eagles. His emotionless attitude is merely a grim-faced acceptance of a world populated with machines posing as animals, which are designed to bring pleasure to human beings. Where a film such as The Matrix (1999) depicts machines as being reliant upon humans, Blade Runner hypothesises that machines are made not just to serve mankind, but have become their own integrated population. Because of their falsehood, the manufactured ‘animals’ are by definition a corruption of the natural process of reproduction. This is an important theme in the film: the blurring of boundaries between Nature and humanity.

Because of the ease with which animals are manufactured, any adoration or awe they would inspire as living creatures in our world is completely void. Such is their commonplace distribution that the denizens of Blade Runner are entirely accepting of and at ease with them. What makes this aspect of integration with machines more unsettling is the fact that the audience too must accept these machines as being ‘animals’. Indeed, Tyrell Corporation,the manufacturer of animals and Replicants, even uses the motto ‘More real than real.’ It is because of this integration that animals are used in exposing Replicants: their rarity defines them as something that should be treasured and respected, emotions that man-made machines simply cannot fathom. The first reference to an animal occurs in an empathy test at the film’s opening. Replicant ‘Leon’ is presented with a scenario, to which he responds with increasing anxiety: ‘You see a tortoise. You flip it on its back… you’re not helping.’ Leon interrupts: ‘What do you mean I’m not helping?’ His nervous disposition and eye movement identifies him as Replicant, a result of his inability to empathise with a living creature’s suffering. Blade Runner proposes that machines can be exploited to ape Nature so accurately that it becomes nearly impossible to determine the real from the fake. This is an interesting divergence from the science-fiction genre, in that the film is very guarded in showing the technology behind the animals and Replicants. Where The Terminator (1984) for example explicitly draws attention to the antagonist’s robotics, Blade Runner conceals any hint of mechanical workings, and this highlights the melding of boundaries between biological and artificial life.

The imitation yet-life-like nature of the animals evokes a sense of unease from the audience; as the cold and emotional indifference of the Replicants serves as a reminder of their in-humanness, so too does the animals’ falseness leads us to question what exactly is real within the film. A key scene is when Deckard is sent to test Rachel, a suspected Replicant. He waits in a lobby where a large owl sits on a perch, a haze of dust drifting across the dimly lit scene. This lighting aspect is a clear nod from film noir, a visual technique that warns us that everything we see is not to be trusted. From the shadows, a female voice (Rachel) asks: ‘Do you like our owl?’ to which Deckard responds with a question: ‘It’s artificial?’ The voice answers: ‘Of course it is.’ This third line encapsulates the perception of animals in Blade Runner. That is, the somewhat sardonic ‘Ofcourse’ is a loaded term; loaded in the sense that Rachel, herself a human creation, clearly feels that it is obvious that the bird would be artificial. James Gunn writes: ‘Science-fiction is the branch of literature that deals with the effects of change on people.’ The issue then with Blade Runner as science-fiction is that the ‘change’ – the loss of living animals – has not affected any of the characters emotionally and this is further indicative of technology’s relentless march.

Tyrell Corporation’s artificial owl

Though empathy tests expose a machine’s inability to feel compassion for life, animals are also represented as being indicators of social status. Real animals represent the owner’s standing of considerable wealth and power, and thus fake animals outline the divergence of social classes. The best example is a female Replicant who performs erotic dance with a snake. Deckard tracks her down, in a sequence influenced by film noir. That is, the detective works alone collating clues while the suspect Zhora embodies the classically dangerous ‘femme fatale’. When he asks if the snake is real she replies: ‘Of course it’s not real. You think I’d be working here if I could afford a real snake?’ Her response ‘Of course’ is identical to Rachel’s own about the owl. Where a snake in reality would be seen as exotic and intriguing, the film shows that even a life-like imitation is a relatively worthless commodity if a person is not in a position of success.

Animals are also representative of peace. In Deckard’s battle with the Replicant leader, he is saved from falling to his death by the android. As the machine expires, he releases a dove he held, setting up a beautiful shot of the white bird flying away against the smog-infested skyline. While the dove is a well-known peace symbol, its use as a symbol of co-existence between man and machine is significant. As the Replicant dies he realises the value of life, the dove a metaphor for the freedom every living creature is entitled to.

Roy Batty, leader of the Replicants, holding a dove

One film that I propose shares a strong connection with Blade Runner is post-apocalyptic sci-fi 12 Monkeys (1995). When Earth is contaminated with a deadly man-made virus, humans must exist underground, while unaffected animals roam the surface. The films are linked by the emphasis placed on the image of the animal, real or not, as able to endure change. That is, despite being mechanical the beasts in Blade Runner are ‘real’ in the sense that they are material possessions that capture the extinct beauty of animals. Conversely, 12 Monkey’s animals are live and kicking in abundance, yet are completely inaccessible by humans. They survive despite the disappearance of human beings, an indicator that while mankind can destroy itself, Nature alone can endure even the most catastrophic events. The use of sci-fi as its primary genre allows the film, like Blade Runner, to explore the repercussions of humanity’s exploitation of science, contrasting this with the animals’ ability to exist without technology.