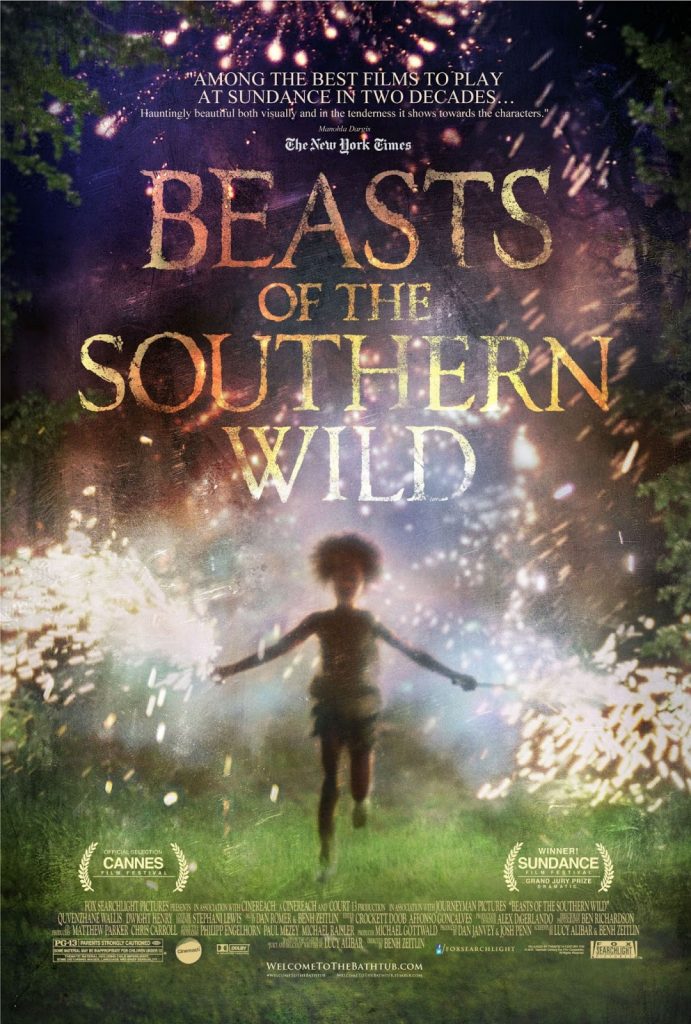

Beasts of the Southern Wild is set in Bathtub, a poor and very ethnically-mixed community in the Louisiana Bayou separated from other civilisation by a levee, a backdrop which conjures up the still fresh memory of Hurricane Katrina. The global warming induced flooding of the area and all that ensues are focalised through the imagination of the film’s six-year old protagonist, Hushpuppy (played by Quvenzhané Wallis), whose dying father Wink (played by Dwight Henry) will shortly leave her an orphan. Both environmental and familial/community-based disaster are juxtaposed with the re-emergence of aurochs: giant, carnivorous, pre-historic pig-like creatures that had been frozen in the ice caps for a vast number of years. Receiving 86/100 from 41 critics [1] Beasts of the Southern Wild was received in 2012 to what is considered almost universal acclaim. The fantasy-drama film was co-adapted by Lucy Alibar and director Benh Zeitlin from the one-act play Juicy and Delicious, written by Alibar.

This is not a film that sits comfortably inside a single genre, rather straddling the line between fantasy, disaster and drama as semi-fictional creatures, the ecological apocalypse and the relationship between a dying father and his daughter all vying for viewer attention. According to Maurice Yacower’s classification, Beasts of the Southern Wild qualifies as a `natural attack` [2], specifically wherein man must compete against the elements. By virtue of its setting in a Louisiana community that has been somewhat forgotten post-Katrina, it `aims for the impact of immediacy`[3] and `dramatizes class conflict` [4] in its depiction of the impoverished residents’ resistance to “rescue” by the better-off and less isolated members of the community from the other side of the levee. The film avoids falling into and even calls into question the `tradition in the fantasy film that identifies marginalized social groups as monstrous threats to the dominant social order` [5] by virtue of its African-American protagonists and dramatic realism. Beasts of the Southern Wild continues in the tradition of drama films such as Kes (dir. Ken Loach, 1969) by using non-professional actors from the area in which the film is set and voice-over by the protagonist in non-speaking scenes. In keeping with this social realism, rather than the fantasy genre, Zeitlin avoids the use of CGI to animate the aurochs. Instead he uses Vietnamese pot-bellied pigs dressed in nutria skins, with added foam shaping and latex horns, in order to `make them look like fearsome beasts` [6]. Beasts of the Southern Wild, much like Life of Pi (dir. Ang Lee, 2012) and Where The Wild Things Are (dir. Spike Jonze, 2009), uses its fantastic element to construct a bildungsroman narrative. Bringing this together with the disaster genre, as Life of Pi does, enables a bildungsroman in which the child is forced to learn how to survive without any parents somewhat prematurely, thus pitting the child against the uncaring natural world. Whereas Life of Pi’s protagonist is distinctly adolescent, six year old Hushpuppy is even younger than the nine year old Max of Where The Wild Things Are yet endures the same complex relationship with her parent, albeit with a far bleaker conclusion.

The aurochs, perhaps conjured from the imagination of Hushpuppy, provide the fantastic element. A brief search of the internet will tell you that the actuality of aurochs in history is quite different to the interpretation shown on film, aurochs being cattle-esque creatures, a species of which existed in some parts of Poland as late as the seventeenth century [7]. Ray Tintori, second-unit director, defended Beasts of the Southern Wild’s factual inaccuracies concerning the aurochs as a combination of artistic license and technical requirements: ‘we figured we could make them whatever we wanted to make them. At the very outset, we knew that the only two options were dogs and pigs, because those are the only two animals smart enough.’ [8] Nonetheless, the appearance of the aurochs within the film is still regarded as the re-emergence of a long extinct species. Zeitlin’s move away from scientific accuracy in raising aurochs to a higher level of intelligence than the bovine allows him to establish a rapport between Hushpuppy and the beasts. This requires some anthropomorphisation (i.e. suggesting that aurochs have the same decision making capacity as humans), which there is room for within the genre of fantasy. In arriving out of the melted ice-caps, the aurochs are presented as a force of nature beyond the control of mankind, summoned by its actions, therefore acting as a summation of the film’s interest in ecology. Interactions between the human and the animal form a part of the greater relationship between humanity and the environment, or humanity and the network of living and dead beings. As a result, animals represented as food is an issue that is allocated a not insignificant amount of time, with fishing, the killing and cooking of an alligator and a sequence in which Hushpuppy learns how to break open a crab shell with her bare hands. These are skills that she will require not only to prevent starvation but also to establish herself as an apex predator, as her mother did (`the American alligator is the apex predator of the marshlands in the southern United States`). [9]

For a film in which there is such a significant animal presence, there is only a very small amount of animal anthropomorphisation, it being chiefly concerned with a rejection of anthropocentricism and human exceptionalism. Hushpuppy, is encouraged to ‘beast it’ [10] by her father, to reject the tools of civilisation (in this case, a knife with which to open a crab shell) and use her animal capabilities in order to survive. Hushpuppy, her community and the film as a whole reject the comforts of the world beyond the levee (being `plug[ed] into the wall` [11]) as limiting of personal freedom. Beyond the levee they become refugees, victims of nature’s evil, looked upon as inferior by the people that live there. Self-sufficiency becomes a point of pride and dependence upon technology for survival looks like selfishness in the face of the ecological system. The death of the weak is a necessity that facilitates the survival of the strong in such a system. There is no anxiety about the ethics of consuming animals, with six year old Hushpuppy saying in a very matter of fact manner `if daddy don’t get back soon it will be time for me to eat my pets` [12] (at this point in the film she is alone and narrating to herself, or the audience if we consider her to be breaking the fourth wall). However wild she is, Hushpuppy is very aware of her reliance on her dying father, as much of a trauma to her as the flooding is to the Bathtub community.

The aurochs are thus a product of Hushpuppy’s anxiety about being left alone. Miss Bathsheba tells us that aurochs in the prehistoric past consumed human beings (`they would gobble the cave-babies down right in front of their cave-parents. And the cavemen couldn’t do nothing about it` [13]), a metaphor for the way in which an individual, particularly a child, can be consumed by the systems of the world. As well as being the apex predator, aurochs are shown on screen consuming their own weak. Whilst, for the most part, human beings do not act cannibalistically, this does demonstrate the way in which fringe groups and minorities often find themselves abandoned or abused by mainstream society. In learning not to fear the aurochs but to command them, Hushpuppy masters the skills she needs both in order to survive in the natural realm and to make her presence felt within the social realm. Neither man nor the aurochs are evil for their consumption of other beings but simply doing what is necessary to exist. In both ecological and social systems, only the strongest or best equipped survive.

As a result of this attention to rationalising Hushpuppy, Wink and their community within the natural world and not within modern human civilisation, animals permeate the mise-en-scène of Beasts of the Southern Wild without needing to have any significant interaction with the humans. This does not, however, mean that a greater focus is being placed upon Hushpuppy’s interaction with other humans as there are also a large number of ethnically diverse human extras. Likewise, although the media-focus is almost always directed towards human casualties in both disaster films and media-coverage of real life disasters, we see almost nothing of them. We see the aurochs consume one of their own in desperation for food and the camera lingers on the body and entrails of a dead dog whilst Hushpuppy contemplates the nature of death, saying `everybody loses the thing that made them` [14] as a reminder that, as she is a product of her father, man is a product of nature and evolution. Hushpuppy earlier expresses sadness for the animals that drowned during Bathtub’s flooding, acknowledging that human intervention could have, but did not save them (`for every animal that didn’t have a Dad to put it in a boat, the end of the world already happened`). [15] This harkens to the, largely unmentioned, tragedy of the loss of animals lives during Hurricane Katrina and other such disasters in which human lives are prioritised.

Beasts of the Southern Wild thus becomes a critique of the way in which the ecological damage wrecked by humans upon our environment, and especially the way in which other species becomes the innocent victims of such damage, is viewed (or more ostensibly not viewed). Those living on the fringes of society because of poverty and race are far more likely to feel the effect of such damage than others, Louisiana being used as the setting in order to show Hurricane Katrina as a case study of such ideas. 93% of those that were killed during Hurricane Katrina were black, 68% were considered impoverished, `having neither money in the bank nor a usable credit card` [16], all statistics considered showing that `during disasters, poor people, people of color, and the elderly die in disproportionate numbers` [17]. On the fringes of social existence, the human protagonists of Beasts of the Southern Wild feel a greater closeness to nature and to animals than other human beings do not. Whilst in part, this is because of their shared victimhood in the ecological atrocities, it is also because a white-dominated, capitalist society is structured to reject them in ways the natural world is not.

By virtue of this kinship, Hushpuppy, and through her voice-over, the film itself, develop a philosophical understanding of the complex relationship between human beings and the animals that provide for them through death in the same way that human beings, in prehistory, according to the film’s mythology, provided for aurochs through their death. However, it is important that animals do not die needlessly because it upsets the very fine ecological balance. `I see that I am a little part of a big, big universe, and that makes things right` [18]. Hushpuppy returns triumphantly to her father with cooked alligator, thus having asserted herself as the apex predator in the natural fashion, just as her mother did. The aurochs emerge out from the hill behind Hushpuppy, who refuses to run from them. The framing of this shot means that, for a few moments, she occupies the position of pack leader and the aurochs are travelling in her wake. The camera zooms in and pans upwards so that it is Hushpuppy’s face that fills the shot rather than the herd of monsters behind her so that, in the moment before she turns to confront the lead auroch, Hushpuppy seems larger than the monsters following. Zeitlin then cuts to this wide shot:

Hushpuppy is tiny in comparison to the auroch she stares down towards the film’s closing, small and unthreatening to the animal which comes to represent the aggregated anxieties of both herself, alienated social groups and humanity as a whole. Whilst she may conquer her personal struggles for survival and social acceptance and make the beasts of her nightmares bow before her, Hushpuppy is still very small compared to the large, complex systems the aurochs stand as metaphor for. Humanity on the other hand takes up too much room and needs to learn to be small, like a six-year old girl, in order to survive, though man can still be master of his environment.

Filmography

Beasts of the Southern Wild, dir. by Benh Zeitlin (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2012).

Life of Pi, dir. by Ang Lee (20th Century Fox, 2012)

Where The Wild Things Are, dir. by Spike Jonze (Warner Bros., 2009)

Bibliography/Suggested Further Reading

Alibar, Lucy, Juicy and Delicious (New York: Diversion Books, 2012)

Arons, Rachel, A Mythical Bayou’s All-Too-Real Peril: The Making of `Beasts of the Southern Wild` (New York: The New York Times, 2012) https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/10/movies/the-making-of-beasts-of-the-southern-wild.html

Bellin, Joshua David, Framing Monsters: Fantasy Film and Social Alienation (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005)

Berlin, J.,Exclusive: The Secret of the Aurochs (Those “Beasts of the Southern Wild”), (Washington: National Geographic, 2012) https://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/2012/07/17/exclusive-the-secret-of-the-aurochs-those-beasts-of-the-southern-wild/ (accessed 27th November 2013).

Coren, Stanley, `The Dogs of Hurricane Katrina` in Modern Dog https://moderndogmagazine.com/articles/dogs-hurricane-katrina/151

Ebert, Roger, Beasts of the Southern Wild (Chicago: rogerebert.com, 2012) https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/beasts-of-the-southern-wild-2012

Heldman, Caroline, Hurricane Katrina and the Demographics of Death (Los Angeles: Sociological Images, 2011) https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2011/08/29/hurricane-katrina-and-the-demographics-of-death/ (accessed 27th November 2013).

Maas, Peter, Aurochs – Bos primigenius, (Eersel: The Sixth Extinction, 2011) https://www.petermaas.nl/extinct/speciesinfo/aurochs.htm (accessed 27th November 2013).

Metacritic, Beasts of the Southern Wild, (San Francisco: Metacritic, 2012) https://www.metacritic.com/movie/beasts-of-the-southern-wild (accessed 27th November 2013).

Wilson, David, `Deadliest Predators In The US` in The Adrenalist, https://www.theadrenalist.com/adventure/deadliest-apex-predators-in-the-u-s/ (accessed 18th January 2014)

Yacower, Maurice, The Bug in the Rug: Notes on the Disaster Genre in Film Genre Reader IV, ed. Barry Keith Grant (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012) pp. 313-331

Yaeger, Patricia, Beasts of the Southern Wild and Dirty Ecology (Atlanta: Southern Spaces, 2013) https://southernspaces.org/2013/beasts-southern-wild-and-dirty-ecology

[1] Metacritic, Beasts of the Southern Wild, (San Francisco: Metacritic, 2012) https://www.metacritic.com/movie/beasts-of-the-southern-wild (accessed 27th November 2013).

[2] Maurice Yacower, The Bug in the Rug: Notes on the Disaster Genre in Film Genre Reader IV, ed. Barry Keith Grant (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012) pp. 313-331, p. 314

[3] Ibid. p. 320

[4] Ibid. p. 321

[5] Joshua David Bellin, Framing Monsters: Fantasy Film and Social Alienation (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005) p.2.

[6] J. Berlin, Exclusive: The Secret of the Aurochs (Those “Beasts of the Southern Wild”), (Washington: National Geographic, 2012) https://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com/2012/07/17/exclusive-the-secret-of-the-aurochs-those-beasts-of-the-southern-wild/ (accessed 27th November 2013).

[7] Peter Maas, Aurochs – Bos primigenius, (Eersel: The Sixth Extinction, 2011) https://www.petermaas.nl/extinct/speciesinfo/aurochs.htm (accessed 27th November 2013).

[8] National Geographic, Exclusive: The Secret of the Aurochs.

[9] David Wilson, `Deadliest Predators In The US` in The Adrenalist, https://www.theadrenalist.com/adventure/deadliest-apex-predators-in-the-u-s/ (accessed 18th January 2014)

[10] Beasts of the Southern Wild, dir. by Benh Zeitlin (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2012) [on DVD].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Caroline Heldman, Hurricane Katrina and the Demographics of Death (Los Angeles: Sociological Images, 2011) https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2011/08/29/hurricane-katrina-and-the-demographics-of-death/ (accessed 27th November 2013).

[17] Ibid.

[18] Beasts of the Southern Wild, dir. by Benh Zeitlin.