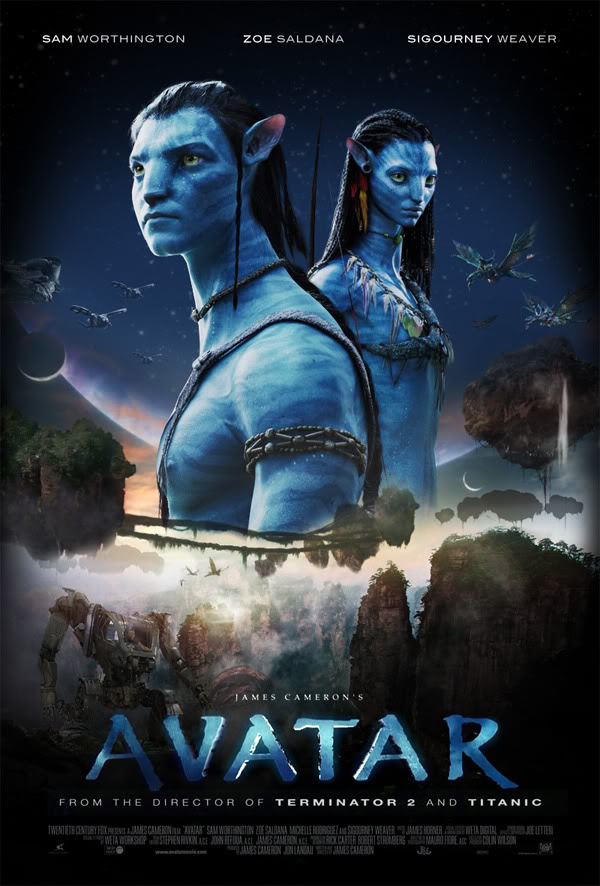

Set in the year 2154, Avatar (Dir. James Cameron, 2009) follows Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic ex-marine who is given the opportunity to take part in a program on the distant moon Pandora. Pandora is inhabited by a wealth of creatures and biodiversity, as well as the desirable mineral ‘unobtanium’ which the humans are attempting to mine. Unfortunately, the richest deposit of unobtanium lies beneath the home of the indigenous race of ‘humanoids’ [1] the Na’vi. Sully’s role is to remotely control the manmade Avatars, made up of half human half Na’vi DNA, build relations with the Na’vi people and negotiate their resettlement elsewhere before the leader of Security Operations, Colonel Quaritch (Stephen Lang), attempts to destroy Hometree and the Tree of Souls. However, in his position as an infiltrator and a spy for the RDA, Sully begins to appreciate Pandora and to understand the ways of the Na’vi. He also falls in love with the Na’vi Princess Neytiri who teaches him how to become a Na’vi warrior and part of the Omaticaya clan. Ultimately, Sully realises that to live well is to live in harmony with the other creatures and to support the ecosystem, rather than destroy it.

Highlighting the Earth’s potential fate and portraying extra-terrestrial life, Avatar sits firmly within the Science Fiction genre. The film is also a Fantasy, not just in its depiction of the many fictional beings but also in the magical world it creates with motion capture technology and CGI animation. Its ‘ecocentricity’ [2] places intrinsic value on all living organisms, regardless of their perceived usefulness or importance to human beings. The Avatar franchise also has its own Wiki website, describing every aspect of Pandora as if it were real; most interesting is the index of Pandorian creatures which I thoroughly recommend checking out. [3]

Although Na’vi means ‘The People’ [4] in English, the humans refer to them as ‘the hostiles’, ‘the savages’ and even ‘the blue monkeys’, demonstrating their identification as animals. Physically, the Na’vi differ significantly; they are much larger (3 metres tall) with striped blue skin and slender bodies, and a feline appearance with big amber eyes, long tails and pointed ears which move independently in reaction to sound. Their bioluminescent markings differentiate them further from the human physiology, yet they are ‘the only known extra-terrestrial species [on Pandora] discovered to have human-like consciousness and intelligence’, according to the Wiki page. This brings into question ‘humanness’ as a physical or psychological concept; the Na’vi are not completely dissimilar to us in mind, but in body they are alien. The avatars, combining the human mind with a Na’vi-like body (notable differences include ten fingers and toes as opposed to eight and smaller eyes), differ again; the avatars’ dehumanisation could equally be regarded as the humanisation of the Na’vi. Nevertheless, Sully finds himself equivalent to a Na’vi child as Neytiri declares ‘You’re like a baby! Making noise, don’t know what to do’. This comparison between Jake-as-avatar and a child links to a common theory that developed animals and human children are not dissimilar in their mental capacity and emotions, and thus as we grow up we become more human, less animal. [5] Jake describes the ceremony that will admit him into the Omaticaya clan as ‘the final stage of becoming a man’, granted he means a Na’vi man but the film definitely blurs the lines between what is and isn’t a man.

Jake’s decision to remain in his avatar body and live as a Na’vi also emphasises the apparent fluidity of humanity. As a paraplegic, Jake is prevented from exploring his full humanness and he states that he’s ‘tired of people telling me what I can’t do’. By leaving behind his human life and body, he is able to feel more human due to the use of his legs. This idea is developed over the course of the film with consistent close-ups on feet, a human feature as they allow us to stand up-right and walk on two legs, unlike most animals. Therefore feet symbolise the human-animal boundary. Yet, from the clip of Sully running for the first time as an avatar and revelling in feeling the soil between his toes, an image which is also emblematic of the message that we need to connect more with the Earth, to him clumsily stepping on the Na’vi’s tails and learning how to run and jump through the trees whilst maintaining his balance, Sully’s feet actually represent his breaking the barrier, using his feet to escape his human existence.

The film shows the Na’vi’s reverence for each other and their fellow creatures on Pandora. This is highlighted by the metaphor of ‘Seeing’, not in terms of sight but in understanding one another, seeing into each other’s soul. The Na’vi people say ‘I see you’, and Norm Spellman (Joel David Moore) explains that ‘It’s not just, “I’m seeing you in front of me,” it’s “I see into you.”‘ Thus the Na’vi people respect their surroundings because they understand how it works, that ‘all energy is borrowed’ and Eywa (their deity) ‘protects the balance of life.’ Neytiri says to Jake ‘Sky people cannot learn. You do not See’, to which Jake replies ‘Then teach me to See’. Significantly, it is the blindness of humans that works against them in their attack on the Tree of Souls, because they have to rely on sight rather than technology to guide their way through ‘the flux’. The final shot in Avatar confirms this idea, showing the eyes of Jake in his avatar body pop open which is ‘not just about the transformation from human to Na’vi, but also about a new signification of self'[6], a new vision.

With Pandoras’s ecosystem displaying ‘tangible’ bioneural connections between all living beings, the Na’vi consider themselves on virtually equal terms with the other animals on Pandora, and do not needlessly kill anything when possible. Even their concept of marriage is referred to in animal terms: ‘mated for life’. It is this equal relationship, signified by ‘the bond’ they are able to make with the Direhorses and the Banshees, which leads to their winning the battle against the humans as the many Pandorian creatures come to help the Na’vi. The image of the Thanator, ‘the apex land predator on Pandora’ [7], bowing to Neytiri and allowing her to bond with it and ride it in battle is significant; the bond is made through a mutual choice and the Na’vi do not use the animals against their will. Moreover, by making the bond the Na’vi literally become one, mentally, with the animals. Jake Sully benefits in particular from the creatures when he bonds with the Great Leonopteryx and becomes Toruk Makto, the legendary leader who is able to unite the clans, which plays a significant part in defeating the humans. Therefore, the Pandorian creatures all play a crucial role in protecting their home.

In Jake’s first expedition as an avatar he encounters various unknown creatures and the hierarchy that he is accustomed to as a human on Earth is undermined by his ignorance in this new environment. The threat of the unknown creates a rift between the humans and the non-humans in this film, and their ability to destroy his human equipment and escape unscathed from his gun shots intensifies their natural power. The idea that all the creatures are connected links to the Darwinian theory of the ‘Entangled Bank’ [8], which highlighted the way that all beings rely on each other to survive. For the Na’vi and the other Pandorian creatures though, this is more than a theory; Neytiri explains ‘all energy is only borrowed’, illustrating the Na’vi’s humble way of life. The film not only questions what it is to be human, it also considers what it is to be humane; if the Na’vi are more humane than the humans, the boundary between human and non-human is undoubtedly critiqued and the viewer must contemplate whether in a technological age, we are losing our humanity.

Avatar’s obvious environmental message and science fiction genre could be compared to a film like Godzilla (Dir. Ishirō Honda, 1954) which uses an extra-terrestrial creature to warn the viewer against nuclear warfare. Both argue for a more peaceful way of life, both allude to the destructiveness of technology and champion a more natural way of living. However, the crucial difference is that Avatar focuses on a different world to ours, Pandora, to emphasise how we should be living rather than what might happen once we fail to do so. There is an allusion to Earth when Sully tells Eywa, ‘There’s no green there. They killed their mother’ but in actuality the film barely spares a thought for Earth, sending most of the humans ‘back to where they came from’. Godzilla on the other hand deals directly with the potential outcome of nuclear war, using the animal to illustrate the threat to humanity rather than the saviour of humanity.

Bibliography

- Avatar Wiki, Wikia, (No date)http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Na%27vi [Accessed 04/01/2016]

- Darwin, Charles, ‘Online Variorum of Darwin’s Origin of Species: sixth British edition (1872), page 429’, Dawrin Online, (2002) http://darwin-online.org.uk/Variorum/1872/1872-429-c-1869.html [Accessed 06/01/2016]

- Darwin, Erasmus, ‘The Expression of the emotions in man and Animals’, ‘A biographical sketch of an infant’, ‘Darwin’s Observations on His Children’, Darwin Correspondence Project: University of Cambridge, (1872, 1877, 2016) https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/observations-on-children[Accessed 06/01/2016]

- Falquina, Silvia Martínez, ‘“The Pandora Effect:” James Cameron’s Avatar and a Trauma Studies Perspective’, Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, 36.2, (2014) pp.115-31.

- Ng, Jenna, ‘Seeing Movement: On Motion Capture Animation and James Cameron’s Avatar’, Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 7.3, (2012) pp.273-286.

Further Reading

- Collins, Marsha S., ‘Echoing Romance: James Cameron’s Avatar as Ecoromance’, Mosaic, 47.2 (2014) pp.103-119.

- Hillis, Ken, ‘From Capital to Karma: James Cameron’s Avatar’, Postmodern Culture, 19.3 (2009)

- Humane Hollywood, ‘Avatar’, American Humane Association, (2013) http://www.humanehollywood.org/index.php/movie-archive/item/avatar [Accessed 08/01/2016]

- König, Christiane, ‘Not Becoming-Posthuman in the Ultimate Postfilmic Posthuman Male Fantasy – Queer-Feminist Observations on James Cameron’s Avatar (2009)’, Gender Forum, 32 (2011)

- Wolpe, Paul Root, ‘Review of James Cameron’s Avatar’, AJOB Neuroscience, 1.2 (2010) pp. 72-74

- Wood, Aylish, ‘Where Codes Collide: The Emergent Ecology of Avatar’, Animation, 7.3 (2012) pp.309-322.

[1] Avatar Wiki, ‘Na’vi’, Wikia, (No date) http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Na%27vi [Accessed 04/01/2016]

[2] Silvia Martínez Falquina, ‘ “The Pandora Effect:” James Cameron’s Avatar and a Trauma Studies Perspective’, Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, 36.2, (2014) pp.115-31 (p. 121).

[3] Avatar Wiki, ‘Creatues’, Wikia, (No date) http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Category:Creatures [Accessed 04/01/2016]

[4] Avatar Wiki, ‘Na’vi’, Wikia, (No date) http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Na%27vi [Accessed 04/01/2016]

[5] Erasmus Darwin, ‘The Expression of the emotions in man and Animals’, ‘A biographical sketch of an infant’, ‘Darwin’s Observations on His Children’, Darwin Correspondence Project: University of Cambridge, (1872, 1877, 2016) https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/observations-on-children [Accessed 06/01/2016]

[6] Jenna Ng, ‘Seeing Movement: On Motion Capture Animation and James Cameron’s Avatar’, Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 7.3, (2012) pp.273-286 (p.284)

[7] Avatar Wiki, ‘Thanator’, Wikia, (No date)http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Thanator [Accessed 04/01/2016]

[8] Charles Darwin, ‘Online Variorum of Darwin’s Origin of Species: sixth British edition (1872), page 429’, Dawrin Online, (2002) http://darwin-online.org.uk/Variorum/1872/1872-429-c-1869.html [Accessed 06/01/2016]