The murder of three small dogs one after the other is not what most people would think of as funny. Yet this exact progression becomes a running gag in Charles Crichton’s heist comedy film A Fish Called Wanda, where stuttering animal lover Ken’s failed attempts to kill an old woman (who is witness to the robbery) results in the inadvertent death of her pets.

In the scene where the second dog meets its fatal end, Ken’s slow pursuit of the old woman in his car pastiches a typical chase scene in a crime drama, as the threat here is an elderly woman, who is conventionally viewed as a harmless member of society. Throughout the film, the old woman is portrayed as irritating and mean-spirited, and her dogs are emphatically aligned with her, illustrated here with the sound of yapping that mingles with the old woman’s reprimand of a passerby. Dramatic music evocative of a crime drama accompanies the pursuit, which is humorously prolonged and exaggerated, increasing in volume until it climatically cuts with the car crash, so that only the diegetic sounds of brakes screeching and the car colliding with the skip is heard. This deadpan effect is compounded by the subsequent close-up shot of the dead dog where only the sounds of rolling cans are heard, but it is when the shot flicks to Ken’s melodramatic heartbroken reaction that the scene displays the true object of humour. Ken’s obsession with animals, coupled with his stutter, is seen as a ‘quirk’ of his character so that we can both laugh at and pity him, and the theatrical elements of the scene are used as a ploy to accentuate his eccentricity.

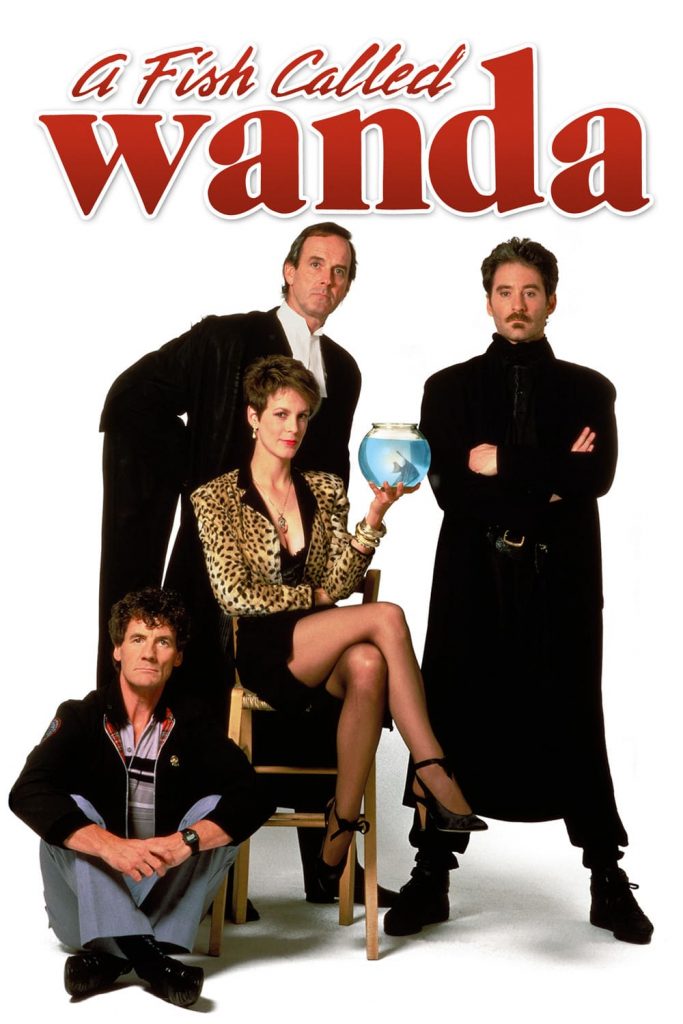

Ken and his beloved fish.

The reactions are central to the humour: a medium close-up of the old woman’s shock which causes her to fall to the ground is followed by a mid shot of Ken’s response, who, wide-eyed and mouth open, turns his head overly slowly towards the camera, and runs off down the road, accompanied by diegetic sounds of the old woman’s anguish. This sense of melodrama exposes the root of the humour: that Ken places more value on the death of an animal than a human, so that the inherent ridiculousness of this becomes the joke. His love of animals, along with his stutter, emasculates him so that he becomes a comic villain rather than a villain in a typical crime drama. This emasculation of Ken is apparent in the way the reactions are filmed: his sprint from the scene mirrors the old woman’s fall to the ground, as the shots follow one another, humorously juxtaposing the elderly pet owner’s grief with the murderer’s. The long shot of him running down the road reveals his disguise falling apart, as he attempts to keep his wig on before finally ripping it off, and becomes a emblem for the rupture of his unconvincing persona of a cold-hearted villain.

The obvious artificiality of the straw dog, in contrast to the realistic mise-en-scene, creates a staged effect that becomes another plot device, as we can more easily trivialise the animals’ deaths if they don’t look real. This enables us to laugh at Ken’s failed attempt and his subsequent anguish, playing into the sense of melodrama and creating an anticlimactic effect. This sense of anticlimax and melodrama, compounded by the sparse shot of the dog, imply that pets do not constitute a ‘real’ victim of crime.

However, the artificial dog also sets up a conundrum: whilst it trivialises animal death, it also hints at our culture as pet lovers, as Crichton’s choice implies a more realistic model would be too shocking. Our laughter at Ken’s love of animals is therefore undermined by our own, this current of empathy set against the film’s parodic intention, to ensure we retain a certain affection for the endearing Ken.