‘Even the blind men’s dogs appeared to know him; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts; and then would wag their tails as though they said, “No eye at all is better than an evil eye, dark master!’ [1]

Guide dogs have been a symbol of selflessness and morality throughout history, and the blind man’s dog in A Christmas Carol is no exception. The film utilises the altruistic image of the guide dog because, as Jonathan Burt states, ‘the dog…embodies the moral potential of film itself’. [3] If the purpose of film is to foster a heartening and morally inspiring experience for its audience, then the guide dog is the quintessential cinematic dog. The guide dog possesses the ability to render a story as edifying as it is charming with a combination of adorability and righteousness. By representing a more virtuous, cooperative world, the blind man’s dog provides an example for humans like Scrooge who must learn to embrace goodness if they are to be rid of their self-destructive selfish ways. By placing the guide dog at the beginning of the film, the moral possibilities of the film in terms of Scrooge’s redemptive journey are realised.

The dog and Scrooge are presented in opposition to one another, using an over-the-shoulder shot, as embodiments of the film’s morality and immorality binary opposition. By providing sight for its owner, the dog represents the film’s theme of moral vision. Placing the dog and Scrooge opposite one another brings Scrooge’s blindness to his own egocentrism into direct contrast with the dog’s vision. Enlightened with moral vision, the dog senses Scrooge’s selfish character and cowers and whimpers in fear of Scrooge. The film utilises the sensitivity of the species to emphasise the dog’s ability to empathise with humans, juxtaposing Scrooge’s cold unresponsiveness to those around him, including the frightened dog.

The establishing shot of the scene is a wide shot enabling the dog and Scrooge to be presented in relation to the festive mise-en-scène. The dog is aligned with the festivities as it leads its owner past warmly lit, decorated windows and spectacles such as fire-breathing. Morality, via the dog, is associated with mirth and merriment whereas Scrooge is presented as the opposition to this pleasure with his bleak, immoral values. To establish the threat that Scrooge poses to the goodness and joy, the camera positions the dog as the central image in the frame to focus on its fearful reaction to Scrooge. The placement of Scrooge in the left of the frame with his back turned to the camera encourages the audience to engage with the dog and its values rather than with Scrooge, whilst demonstrating the ostracising effect of selfishness and indifference. Scrooge’s distance from gaining morality and happiness at this point in the film is demonstrated through deep space composition; the considerable physical space between Scrooge and the dog illustrates Scrooge’s detachment from morality and the journey he must undertake to reacquaint himself with moral vision.

The short cinematic duration of the scene renders this symbolic moment a vignette, epitomising the film’s narrative of a man faced with morality but unable to see it or embrace it being blinded by selfishness. The employment of a guide dog to symbolise this morality and convey this momentous message underlines the ethical importance and influence of the guide dog and, more broadly, the value that humans assign to dogs. In the same way that humans trust guide dogs with their lives, the film trusts the guide dog to embody the moral potential of cinema.

The social vision of A Christmas Carol manifests itself in the moral vision of the guide dog. As a symbol of hope, help, social inclusion and companionship, the guide dog is an honourable exemplar for humanity, rendering the guide dog a worthy contender for the title of quintessential cinematic dog.

[1] Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (London: Scholastic, 2013), p. 3.

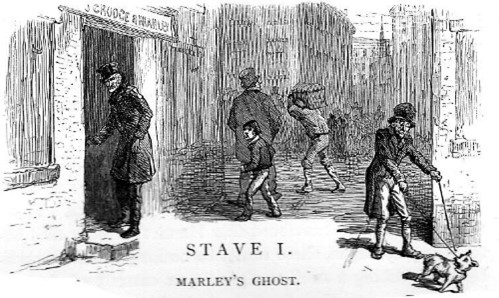

[2] Sol Eytinge, Jr., scanned by Philip V. Allingham, “Scrooge and Marley’s”, vignette for “Stave I. Marley’s Ghost”, digital image of an illustration, Victorian Web, <https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/eytinge/26.html> [accessed 23 December 2021].

[3] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books Limited, 2002), p. 23.

[5] A Christmas Carol, dir. by. Robert Zemeckis (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2009).

[6] Anglia Press Agency, Miller is a guide dog.

[7] A Christmas Carol.

[8] A Christmas Carol.

[9] Anglia Press Agency, Miller guides his owner across the street.

[10] Anglia Press Agency, Miller with his owner, Mr Michaels.

Bibliography

A Christmas Carol, dir. by. Robert Zemeckis (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2009)

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books Limited, 2002)

Dickens, Charles, A Christmas Carol (London: Scholastic, 2013)

Eytinge, Jr., Sol, scanned by Philip V. Allingham, “Scrooge and Marley’s”, vignette for “Stave I. Marley’s Ghost”, digital image of an illustration, Victorian Web, <https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/eytinge/26.html> [accessed 23 December 2021]