‘A lot of people say an octopus is like an alien. But the strange thing is, as you get closer to them, you realize that we’re very similar in a lot of ways.’

There is a popular saying among marine biologists that ‘we know more about the surface of the moon than we do about [the Earth’s sea floor]’, so it is no surprise that marine animals like the octopus are often referred to as ‘alien’ species.[1] However, in an ambitious new endeavour to challenge these notions, the ‘winningly unorthodox’ documentary ‘My Octopus Teacher’ recounts the unlikely companionship between wildlife filmmaker Craig Foster and an octopus living in the Great African Seaforest.[2] After many years working on natural history documentaries, Craig was suffering from extreme burnout until the icy waters of the Western Cape restored his passion for the natural world. But one particular encounter stood out. Over the course of this unique film we see an octopus survive traumatic shark attacks, make physical contact with her human companion and eventually sacrifice her life in giving birth to her young. There is a reason it is entitled ‘My Octopus Teacher’ as opposed to ‘friend’ or ‘companion’; over her short lifetime, the octopus teaches Craig to forge deeper connections with animals and humans, and the film hopes to inspire the same from its viewers by instilling familiar conservational values in a subtle new way.

‘My Octopus Teacher’ is not a standard observational documentary depicting nature existing in the wild. Instead of a detached scientific voiceover, the narrative is structured by an interview with Craig as he recounts the octopus’ tumultuous life and the impact it had on him. Director Pippa Ehrlich describes her immersive approach as ‘experiential filmmaking’ where ‘most of the story was filmed by a team who go diving every day with no wetsuits and no scuba gear.’[3] The result is a film which brings us even closer to a wild animal in its natural habitat, as the team were able to wait for the octopus to come to them, rather than hiding in the shadows with a zoomed in lens.

Craig Foster was inspired to reconnect with nature after filming animal trackers in the central Kalahari. He confesses that ‘they just were inside of the natural world, and I could feel I was outside.’ So when he startles the octopus by dropping a lens soon after their first encounter, he is forced to learn these precise tracking techniques in order to locate her again.

It takes a great deal of time for the octopus to finally allow Craig into her world. However, it is this insistence of keeping him at a distance for so long that forces Craig to learn even more about her kind. She is leading him ever closer to forging a profound connection with nature. And in doing so, she inadvertently teaches him to become a master tracker by being so difficult to locate. Calarco states that ‘to act empathetically requires learning as much as possible about the world an animal inhabits’.[4] Within a film that promotes this degree of animal empathy, the Kalahari trackers are upheld as ultimate examples of this. Thus, in order to access the same level of harmony with nature, Craig decides to take on the role of a detective, seeking out this elusive creature.

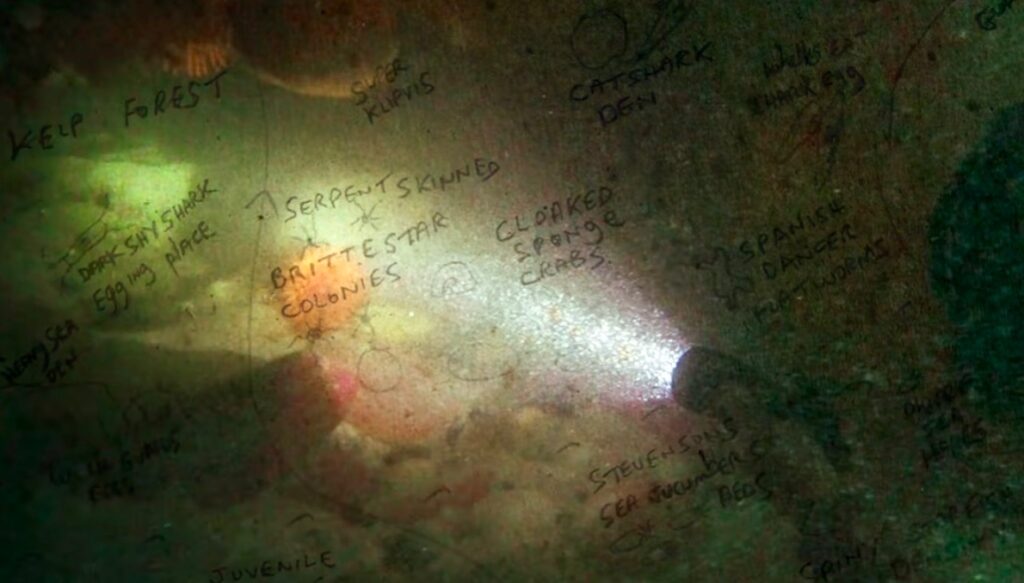

At the start of this scene, Craig insists ‘you have to start thinking like an octopus’ as the camera cuts to a shot of him plotting clues on an evidence board. The soundtrack introduces a suspenseful drum pattern, resembling the music of a tense crime drama. Suddenly something as mundane as observing patterns in the sand becomes incredibly exciting. The film aims to prove that connecting with animals can be truly eye-opening and is not exclusive to scientists alone. Moreover, Craig’s desire to ‘think like an octopus’, just as a detective tries to get into the mind of their suspect, further emphasises how complex these creatures are. He takes this process incredibly seriously, proving that octopuses are often underestimated by humans and cannot simply be put in a box. As Craig points out earlier in the film: ‘a mollusc shouldn’t be this intelligent.’ They ‘frustrate the neat evolutionary division between clever vertebrates and simple-minded invertebrates’ and are far more intelligent than one might initially expect.[5]

As the chase builds to a crescendo, Craig’s notes become superimposed over shots of the deep sea floor, mapping out his internal thought process on screen. However, the darkness of the kelp forest further emphasises how evasive the octopus can be. Craig narrates, ‘this animal has spent millions of years learning to be impossible to find… I needed to learn everything.’ This is an animal that we clearly know very little about and one that, as the film unfolds, will continue to challenge everything we thought we knew already. This early scene introduces notions of profound animal empathy and proves that this remarkable animal is not to be underestimated.

Nevertheless, as in most cinematic narratives, in order for there to be a hero there must also be a villain to provide dramatic contrast. So while the octopus is upheld as awe-inspiring, its predator is knocked down as terrifying and monstrous; the first time pyjama sharks are mentioned in the film, a menacing atmosphere is established straight away as the camera cuts to a shot of them hiding in a small cave.

Here, the pitch black cave is illuminated by a single flashlight, immediately associating the sharks with darkness and uncertainty. Meanwhile, the soundtrack shifts in tone as chromatic tremolo strings underscore the scene. Multiple extreme close-ups follow where the sharks are depicted from a low angle, seemingly staring right into the camera as their sharp teeth take full focus. These close ups suggest a level of fearlessness as the sharks swim right up to the lens. When Craig reveals, ‘they have an incredible sense of smell’ we see one shark mouth breathing heavily, its jaws opening and closing to reveal piercing teeth.

Figures 11&12: Extreme close-up shots of pyjama sharks

In the following shot, the cameraman approaches from behind a shroud of kelp as though afraid of getting too close, as we see two sharks fighting each other. Craig continues by saying, ‘they are particularly aggressive’ while a shot depicts one shark with the other in its jaws. The film figures these animals as violent and fearless with loaded language such as ‘deadly little octopus predators’. In his essay on the classic mode of documentary, Bousé establishes the hero-villain trope as fundamental to modern cinema. He asks, ‘was there any reason, therefore, why [wildlife films] should not also have heroes, or for that matter villains? There was one: none of these things are found in nature.’[6] Why then do we insist on anthropomorphising these creatures into human binaries of good and evil? In this particular case we are so wrapped up in the story of the octopus that it would be difficult to detach these hunt scenes from the emotional depth of the rest of the film. We are aligned with the octopus from the start, so it is unsurprising that we should root for it against the sharks. However, this method of aligning the viewer with either predator or prey is a common occurrence in many wildlife documentaries.

This scene from the BBC documentary ‘The Hunt’ opens on a ‘skinny’ polar bear at risk of perishing from malnutrition.[7] In this instance we are aligned with the predator and root for it to succeed, even as it ambushes an unsuspecting seal. If Craig Foster had undergone a similar spiritual awakening by befriending a pyjama shark rather than an octopus, the film’s depictions of this ‘deadly’ predator would have likely been edited very differently.

But it is the octopus that truly opens Craig’s mind to the wonders of the natural world and even inspires him to reconnect with his family. After having been attacked by a pyjama shark, the octopus loses a tentacle and Craig fears tremendously for her health. However, proving once again how resilient these creatures can be, she manages to grow back a ‘perfect, miniature arm’ which then inspires Craig to rebuild the relationships in his own life.

Figures 14&15: The octopus loses a tentacle but manages to grow it back

When the new tentacle is revealed for the first time the octopus is filmed in the shallows, close to the water’s surface. The effect is this beautiful bright light that is refracted through the water, illuminating the octopus’ miraculous recovery. These extreme close-ups show the octopus in all her colourful glory, in contrast with the murky images of sharks hiding in dark caves. Craig narrates, ‘it gave me a strange sort of confidence that she can get past this incredible difficulty, and I felt in my life I was getting past the difficulties I had. In this strange way our lives were mirroring each other.’ For some critics this mirroring seems like a stretch, as Donaldson argues that ‘this is all about the homo sapien […] projecting his emotional nonsense onto an animal.’[8] However, there is no denying that the directors’ ambitions of illustrating the transformative powers of nature have been achieved. Moreover, Craig does not use his own hardships as a way of explaining the octopus’ trauma but quite the opposite. Instead of ‘projecting his emotional nonsense onto an animal’, he uses the animal’s emotional journey to begin to understand his own. In this respect, the film shifts from ‘an anthropomorphic framework, in which human characteristics are mapped onto animal subjects, to a zoomorphic framework, in which knowledge about animals is used to explain the human.’[9]

Figures 16&17: time lapse footage from both land and sea

In the following shots the cinematography helps to extend these parallels between the human and animal protagonists. A time lapse of Craig watching the clouds go by, followed by a similar time lapse of kelp swaying in the sea forest helps to illustrate the passing of time for both individuals as they continue to develop and recover. The panoramic views of mackerel sky over the Western Cape are mirrored by a low-angle shot of sun beams breaking through the water’s surface, both of which demonstrate the enormity of the natural world and our insignificance within it (whether that be as a human or an octopus). And as these time lapses unfold, Craig admits, ‘my relationship with people, with humans was changing.’

In the aftermath of the octopus’ recovery, Craig invites his son to join his daily dives and even introduces him to the octopus. Later in the film, Craig describes the benefits for a young mind to be so immersed in nature: ‘to see that develop a strong sense of himself, and incredible confidence, but the most important thing: a gentleness. And I think that’s the thing that thousands of hours in nature can teach a child.’ Once again, Craig’s own experiences speak directly to the message of the film: that a deep respect for nature is not only beneficial for the wildlife we hope to protect, but can actually transform us as individuals. As Bousé notes, a well-crafted documentary will portray ‘strong animal characters who could function even more effectively as idealized embodiments of morally and socially desirable qualities.’[10] In other words, a ‘strong animal character’ should inspire positive development in its human counterpart, and thus be worthy of the title ‘Octopus Teacher’.

So what exactly does the octopus teach Craig? She teaches him to become a master tracker like those in the Kalahari. She teaches him to overcome his emotional struggles and reconnect with his family. And most importantly she teaches him the power of connecting with nature. Pippa Ehrlich describes the message of the film as this: ‘if you spend a lot of time in a natural environment you start to feel connected to it and connected to yourself in ways that you could never have imagined.’[11] This film bears many parallels with Werner Herzog’s ‘Grizzly Man’.[12] Both documentaries follow individuals who hope to fully immerse themselves in nature and befriend wild animals in their natural habitat. However Timothy Treadwell, who ultimately died in a bear attack, is a prime example of the lethal consequences of underestimating wild animals and overstepping the boundaries between us and them. By contrast, Craig Foster respects these boundaries and is rewarded with an exceptional companionship. As nature documentaries go, ‘My Octopus Teacher is strikingly heart-over-head’.[13] The footage of the kelp forest is transportive and other-worldly. Yet the more we learn about the octopus in this film, the more we realise that she is not an alien creature, but a highly intelligent and sympathetic animal that is vastly more complex than we could have ever understood.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

My Octopus Teacher, dir. Pippa Ehrlich & James Reed, (Netflix, 2020) <https://www.netflix.com/watch/81045007> [Accessed 10 Jan 2024]

Secondary Sources

[1] Paul Snelgrove, A census of the ocean, online video recording, TEDGlobal, July 2011, 01:00 <https://www.ted.com/talks/paul_snelgrove_a_census_of_the_ocean?subtitle=en> [Accessed 14 Jan 2024]

[2] Sheri Linden, ‘“My Octopus Teacher”: Film Review’, The Hollywood Reporter, 1 March 2021, <https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/my-octopus-teacher-film-review-4136577/> [Accessed 12 Jan 2024]

[3] Sea Change Project, Interview with My Octopus Teacher Director, Pippa Ehrlich, online video recording, YouTube, 31 August 2020, <https://youtu.be/05_7vRcggzg?si=PGOocP_BtoF69l7a> [Accessed 13 Jan 2024]

[4] Matthew Calarco, ‘Empathy’, Animal Studies: The Key Concepts, (Taylor & Francis Group, 2020), p.57. <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=6310857> [Accessed 11 Jan 2024]

[5] Amia Srinivasan, ‘The Sucker, the Sucker!’, London Review of Books, 7 September 2017, <https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v39/n17/amia-srinivasan/the-sucker-the-sucker> [Accessed 12 Jan 2024]

[6] Derek Bousé, ‘The Classic Model’, Wildlife Films, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000) p.129. <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=3441988> [Accessed 11 Jan 2024]

[7] BBC Earth, Hungry Polar Bear Ambushes Seal, The Hunt, YouTube, 30 June 2017, < https://youtu.be/zNO0kxTClYo?si=LYxKT-QjAvN-9_Vh> [Accessed 16 Jan 2024]

[8] Kayleigh Donaldson, ‘Why Critics Are Outraged Over “My Octopus Teacher”s Oscar Win’, Pajaba, 2021, <https://www.pajiba.com/film_reviews/theres-a-reason-critics-arent-wild-about-my-octopus-teacher-winning-the-best-documentary-oscar.php> [Accessed 16 Jan 2024]

[9] Cynthia Chris, ‘Introduction’, Watching Wildlife, (University of Minnesota Press, 2006), p. x. <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=322589> [Accessed 13 Jan 2024]

[10] Bousé, ‘The Classic Model’, p.128.

[11] Sea Change Project, Interview with My Octopus Teacher Director, Pippa Ehrlich

[12] Grizzly Man, dir. Werner Herzog, (Lionsgate, 2005) < https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/0115FB38?bcast=33329512> [Accessed 16 Jan 2024]

[13] Elle Hunt, ‘An octopus “love story” on Netflix has caused thoughts to run wild. Why?’, The Guardian, 24 September 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/24/octopus-love-story-netflix> [Accessed 12 Jan 2024]

Further Reading

Elliot, Nils Lindahl, ‘Signs of Anthropomorphism: The Case of Natural History Television Documentaries’, Social Semiotics, 11.3, (2001), p.297. <https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/10350330120032511> [Accessed 11 Jan 2024]

Mitman, Gregg, Reel Nature: America’s Romance with Wildlife on Film, (University of Washington Press, 2009), <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=3444506> [Accessed 11 Jan 2024]

Pollo, Simone, Mariuccia Graziano and Cristina Giacoma, ‘The ethics of natural history documentaries’, Animal Behaviour, 77.5, (2009), <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003347209000694> [Accessed 11 Jan 2024]

Porter, Pete, ‘Film Review: My Octopus Teacher, directed by Pippa Ehrlich & James Reed’, Society & Animals, 31.2, (2023), pp.277-9, <https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1163/15685306-bja10074> [Accessed 12 Jan 2024]

Reid, Vanessa, ‘My Octopus Teacher’, Biodiversity, 21.3, (2020), p.168 <https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/14888386.2020.1847684> [Accessed 12 Jan 2024]