September 2023 saw Wes Anderson’s return to the works of Roald Dahl with the cinematising of The Rat Catcher. In true Andersonian fashion the film foregrounds aesthetic and framing in order to focus our attention on the visual/character design of The Ratcatcher. Anderson uses animalisation to represent the rat via a human and aided by Ralph Fiennes’ performance, the rat-like appearance and personality of the titular character encourages a discussion of the human-rat relations and how the social treatment of and discrimination against both relates.

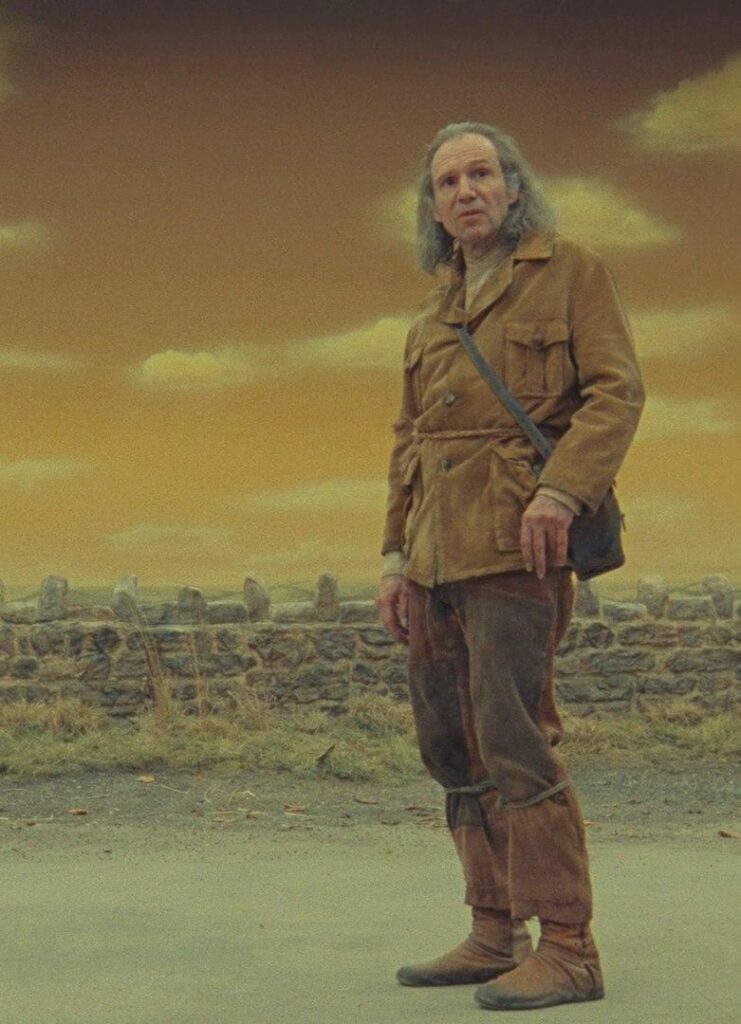

The film begins with an introduction from the news reporter (Richard Ayoade). The cinematography works to use the centrality and symmetry of the frame to focus the attention of the viewer, a trait very typical of Anderson’s films. In sidles The Ratcatcher, centre frame (image below). Immediately, Fiennes’ character is described by the reporter as being “lean and leathery with a sharp face and two sulphur coloured teeth,” pretty ratty, right? Fiennes’ mannerisms accentuate the described features and in collaboration with the Andersonian framing the rattiness of the character is emphasised. The animalisation of the character shows the audience how humans are discriminated against in the same way as rats because the character embodies both rat and human. In creating a rat-like-man, the film engages with the typically negative views society holds of rats and projects them on to the man.

00.01.22

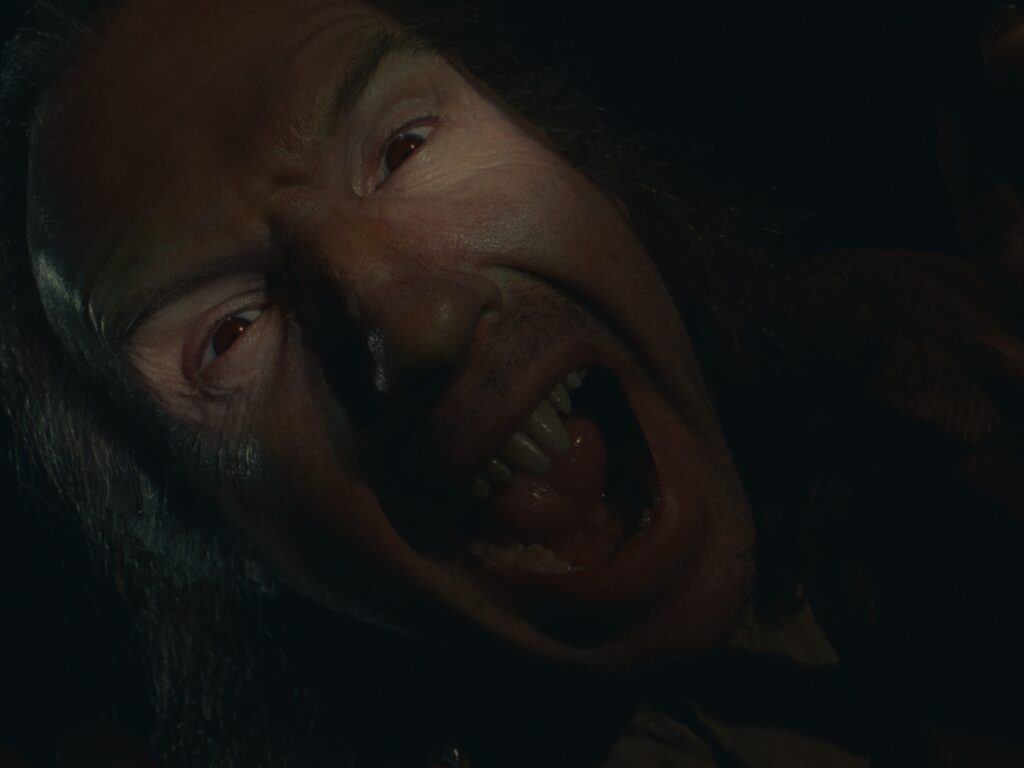

Further, the film’s self awareness achieved by the narrator’s breaching of a fourth wall gives Anderson the ability to channel into what the viewer is thinking. This makes the reporter’s outburst even more relatable when he cries out what we were all thinking, “You’ve almost got to be a rat yourself!” Here, Anderson distances the audience from the Ratcatcher who is becoming more rat-like as the film develops whilst simultaneously calling out the audience for their judgements. This suggests that the more rat-like the catcher becomes the more of an outsider he becomes. This is supported by the fact that, in most western societies rats are held in poor view, they are widely believed to be dirty, disease carrying animals which live on the outskirts of society, pariahs in their own right. The relation between human and rat here, is illustrated by the way The Ratcatcher is distanced from society and Anderson uses the rattiness of character to do this. It is by association with rats that the catcher is outcasted.

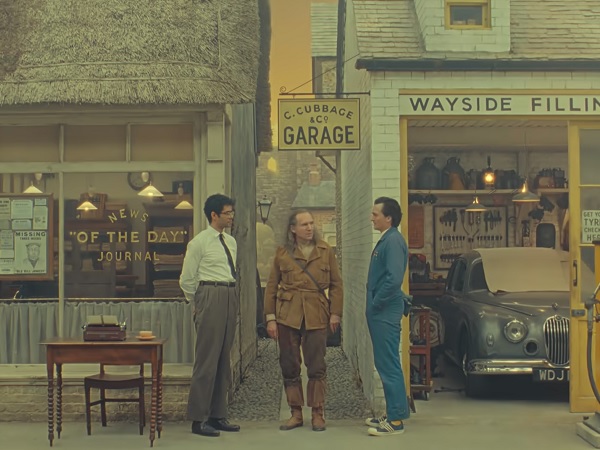

Anderson reinforces the idea of The Ratcatcher as an outsider when Claude and the reporter are looking out to the hayrick which the catcher is stood next to. The colour pallet of The Ratcatcher’s costume matches the wild environment he stands in, to the point where his clothes seem to be natural camouflage, like that of a rat, here the visual design of both set and character equate human to rat, allowing Anderson to characterise him as an outsider. In addition, the framing positions him on the other-side of a fence to the other two in foreground of the shot, adding to the idea of him being an outsider and separate from society. This form of shot composition is one which is more commonly used in The Western genre to symbolise the distance between civilisation/wild, member of society/outlaw and is a shot we see in other works by Anderson for example Fantastic Mr. Fox. Here it works in a similar way to signify the distance between The Ratcatcher and society because of his relation to rats. The combined effect of visual/character and set design positions both encourage the animalisation of The Ratcatcher and in doing equates rat and man both as outsiders.

00.06.20

Foregrounding of Mr Fox looking out and set design (colour, environment) emphasis the disconnect and difference between domestic and wild.

Foregrounding of Martha in domestic looking out to the wild as a rider comes into civilisation.

Primary Source:

The Rat Catcher, dir. Wes Anderson. (Netflix, 2023).

Secondary Sources:

Fantastic Mr Fox, dir. Wes Anderson. (20th Century Studios, 2009).

The Searchers, dir. John Ford. (Warner Bros, 1956).