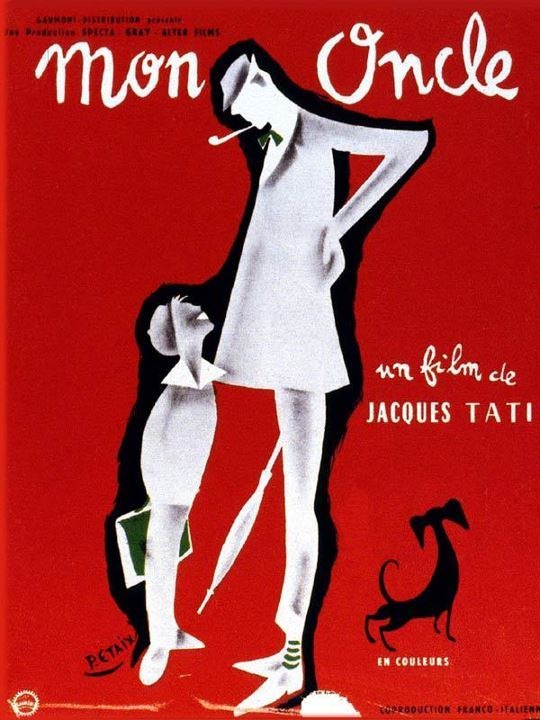

The release of Mon Oncle (Gaumont, France) in 1958 saw the return of Monsieur Hulot to cinema screens, following the successful Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot five years previously. The first of Tati’s films to be released in colour, the film follows the character of Hulot (Jacques Tati), an awkward but incredibly endearing man, and the relationship he has with his nephew, Gerard (Alain Becourt), who adores him. Set against a backdrop of post-war France, Mon Oncle considers the mundane and uncomplicated daily routine of Hulot, shown in contrast to that of his sister (Adrienne Servantie) and brother-in-law (Jean-Pierre Zola), the Arpels, who are fully embracing the modernisation of France and the technological, architectural and social it brings. The film demonstrates these contrasts and Hulot’s navigation of the rapidly developing culture in a humorous and satirical commentary on the French middle class.

Like the majority of Tati’s films, Mon Oncle utilises the concept of silent cinema; the dialogue is extremely limited and is more background noise than anything integral to the plot. This allows the character of Monsieur Hulot to come to the fore. Hulot would have, by now, been a recognisable figure in French cinema as this was Tati’s second film featuring him. A mostly silent character, Hulot’s bumbling physicality and lovably awkward mannerisms are used to convey comedic effect, likening him to silent film stars of the 1920s such as Charlie Chaplin – both distinctive characters appearing in multiple films. The use of silent comedy was somewhat outdated in the time Mon Oncle was released and, therefore, Tati uses it deliberately, preferring to focus on the sound, the lively musical accompaniment and the characters’ physicality. The use of visual comedy is heightened, making the audience more aware of what they are seeing on the screen rather than waiting for verbal cues to convey humour. In this way, while the film does not follow an animal driven narrative, Tati’s use of animals appears in keeping with the genre and style of film; as animals are non-verbal, any comedy, emotion or feeling generated by their presence must be through the visual they create. This leads them to be an excellent vehicle for a film such as this, allowing their presence to give an audience further depth into the picture being created.

Use of Animals

In 2015, video editor Jacob T. Swinney created a supercut of the opening and closing shots of 78 films, placed alongside each other. [1] His intention was to draw something new out of the films, placing emphasis on the themes and the contrasts between the two, suggesting that a lot can be conveyed from the first and last shots of a film.

When applying this technique to Mon Oncle, there are obvious similarities and parallels. The film begins with a shot of a pack of stray dogs, sniffing around piles of rubbish in an old French alleyway. Among them is Dachy, the Arpel’s dachshund, who wears a red chequered coat, marking him out as significantly different from the strays. One particular shot shows the dogs scavenging around a marketplace while a man loads up his horse-drawn cart. The placing of the dogs alongside typical images of the marketplace is something which recurs throughout the film, aligning the stray dogs with the ‘old’ France and separating them from the modernised suburbia. There is only one dog who is able to cross this metaphorical line and that is Dachy; he is clearly domesticated and, as shown, is cleaned regularly by his owner, suggesting that this fact allows him to be deemed acceptable by the humans in the film. He is the symbol of the ‘New France’ which is being satirised as, by following him, the audience is given a view into life on both sides of the city, given his ability to move between both with ease. However, despite his apparent desire to run free, Dachy is inevitably linked to his owners as a domesticated pet. This can be shown in some subtle parallels between their lives and his; like Gerard, Dachy is greeted with horror when he turns up on the doorstep dirty, and, an audience with a keener eye could note that the cuffs of M. Arpel’s smoking jacket are the same colour and pattern as Dachy’s trademark coat.

These small indications further affirm his domesticity, characterising him as an extension of the Arpel family and marking him out as a pet. Tati includes ‘visual smiles’ [2] such as these to garner the audience’s affection for the human/animal relationships being shown.

When viewing the last scene of the film, the ubiquitous stray dogs (and the incorrigible Dachy) are present again. A long-take scene shows the dogs as they, again, scavenge around the marketplace, however, this time the market is empty, a stark contrast to its constant bustle throughout. The audience is placed behind an open window, looking down on the square, as a net curtain gently blows across the space echoing the silent film era, when films would be drawn to a close by a curtain sweeping across the screen. In this case, it appears as a distinct implication that a metaphorical curtain is being drawn over that way of life and what was once the norm is becoming marginalised. However, as the audience can see, the dogs remain a constant, shown in the bookending of the film by these two shots.

Later, we are shown Hulot returning from an evening with the Arpels in a horse-drawn cart. The presence of the horse and its utilisation as a form of transport appears an archaic image within the many shots of modern technology. There is a heavy emphasis on machinery, including cars throughout the film. In one scene, the camera is placed on the bonnet of M. Arpel’s car, accompanied by a soundtrack of fast jazz, followed by a high angle shot of cars in the morning commute as they pass by, three lanes thick. The disparity between these shots and the long-take, long-distance shots used in the opening shots of the dogs creates a sense of tension and tumult, compared to the unhurried nature of the old town. Therefore, the horse and cart are a recognisable motif from the scenes in the marketplace, linking it to the old. Though France was, at the time, seeing a growing reliance on technology; between 1949 and 1958 (when Mon Oncle was released), sales of appliances such as refrigerators and vacuum cleaners increased by 400%[3]; Tati uses scenes such as this to show that before the employment of technology for the ease of humans, there was animals. This reiterates the leisurely pace of the old quarter and its rejection of technology in favour of animals, allowing the animals to be used in the creation of a fond nostalgia.

Comedy

However, to consider Mon Oncle as a film which is desperately pushing a political agenda would be to disregard its main purpose; to make one laugh. Tati himself stated that his intention was ‘not to criticise but to bring a smile’[4], suggesting that any such observations made would come secondary to the comedic nature of the film. Animals have always been worthy subjects for comedy; Claire Molloy describes the ‘comedy spectacle of the humanized animal’[5], claiming that we are able to find animals funny because of their inability to communicate verbally, therefore, allowing us to attribute their behaviour to things which are recognisably human. For example, we can laugh at Dachy’s tartan coat because it is so unnecessary to him that it appears as a fashion accessory, thus creating an image of a pampered and fussy lapdog. Also, given the silent comedy of Tati’s films, he often uses them and, in fact, celebrates them. In Mon Oncle, there is minimal distinction between humans and animals in the film, possibly due to the near-silent nature. As there is a paucity of dialogue, in fact many of the human characters in the film speak in indeterminate noises (heh, uh, hm?), there is no real delineation between humans and animals. The power balance of human/animal is played around with and is, on occasion, humorously subverted. The Arpel’s garage is controlled by a motion sensor which is amusingly triggered by Dachy wandering nonchalantly past, causing them to become locked inside. The shot shows M. and Mme. Arpel comically peering out of the garage’s windows with Dachy calmly lying on his stomach outside it, blissfully unaware of their attempts to get him to pass the sensor again and free them.

The image it creates subverts normal expectations; the humans are in a ‘cage’, the animal given the power to let them out. Although Dachy is unaware of the situation and is not deliberately ignoring them, the anthropomorphising of his actions creates the comedy of the scene. It also pokes fun at human’s reliance on new technology and the potential impracticalities of it, using an animal’s ‘unintelligence’ to send up so-called human intelligence.

Jacques Tati’s films appear, first and foremost, as comments and observations on humanity. They observe the mundane, daily life of people with ‘ordinary’ jobs – Jour de Fete (1949) follows a small-town postman – and the humour there is to be found in that without needing any kind of highly engineered plot. The focus is on people and, therefore, Tati’s inclusion of animals is more than incidental or merely something to raise the ‘cute factor’. This suggests that animals are a part of human life which cannot be ignored and, indeed, must not be. His films showcase the harmony of animal life alongside our own lives and the way these lives fit together. The appearance of animals is also often used to further the comedy, making the animal characters as much a part of the narrative as the humans, as they too are given the agency to create comedic effect.

There is no doubt that Tati is celebrating animals in the same way that he is celebrating the everyday human experience. An audience is shown this through interactions with Hulot, a man who embodies simplicity. For example, his discovery that, by manoeuvring his apartment window and reflecting a beam of sunlight onto a canary’s cage he can cause it to sing, is a moment of particular stillness and calm. Hulot deliberately leaves his window in a position to reflect so that his neighbourhood is serenaded by the bird and his gentle smile indicates the pleasure he gets from such simple and natural moments. Likewise, the majority of animal appearances occur in the old quarter of town or end up there. The connection between the old town and the animals is stated from the start of the film but this does not label them as outdated. It merely shows that they are being celebrated in the same way that the film celebrates the ‘old France’ as they exist as part of it. However, this is not their only domain; Dachy is representative of the new wave of petkeeping, the horses represent the utilisation and labour of animals, while the stray dogs bring a sense of naturalism and social togetherness into the film. It is difficult to see the negativity of modernisation when they are on the screen.

Viewing Mon Oncle today, it stands out as a silent film in an era where this was no longer necessary, due to technological developments. However, Tati shows that, in such a film, large amounts of dialogue are unnecessary. The commanding presences of animals and humans alike can convey the message with precision; a slight nuance of the head here, a nonchalant sitting-down there. Indeed, films with little dialogue appear to make a connection between the animals on screen and the audience more than the contrived emotion in productions such as Marley and Me (David Frankel, 2008), where the emotions are created through one-sided dialogue between a pet and an owner. Mon Oncle, and indeed Tati’s Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953) and Trafic (1971), manage to show the simplicity and, indeed, the necessity of the human/animal relationship, without trying to convey a deeper understanding. The beauty is that we exist alongside each other harmony and that appears to be the real message.

[1] Jacob T. Swinney (via artiede.org), First and Final Frames, online video recording, YouTube, 1 April 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6pMxLGgOzH8 [accessed 23/01/2019].

[2] Roger Ebert, The Great Movies II (New York: Broadway Books, 2005), p.278.

[3] Malcolm Turvey, ‘Tati, suburbia and modernity’, in Screening the Paris suburbs: From the silent era to the 1990s, ed. by Derek Schilling and Phillipe Met (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018).

[4] Malcolm Turvey, ‘Tati, suburbia and modernity’, in Screening the Paris suburbs: From the silent era to the 1990s, ed. by Derek Schilling and Phillipe Met (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018).

[5] Claire Molloy, Popular Media and Animals (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p.86.

Further Reading

Films:

Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953) dir. Jacques Tati – showcases Tati’s previous use of animals in silent comedy

Trafic (1971) dir. Jacques Tati – the last of Tati’s films to feature Monsieur Hulot

The Artist (2011) dir. Michel Hazanavicius – a ‘modern-day’ silent film which also utilises an animal character

Video:

Supraphon6, Jacques Tati – lessons from dogs, online video, YouTube, 20 November 2010 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nDzkromq368 – an interesting interview with Tati regarding his interest in dogs as subjects

Articles:

Spohrer, Jennifer, ‘Consumption and the Construction of Community in Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle’, disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory, 19.4 (2010), 61-72 https://doi.org/10.13023/disclosure.19.10 – insight into Tati’s focus on consumerism

De Valck, Marijke, ‘THE SOUND GAG’, New Review of Film and Television Studies, 3.2 (2005), 223-235 https://doi.org/10.1080/17400300500213552 – some interesting observations on Tati’s use of sound comedy as opposed to just visual

Books:

Gilliatt, Penelope, ‘Jacques Tati: The Entertainers’ (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 1976)

Bibliography

Ebert, Roger, The Great Movies II (New York: Broadway Books, 2005)

Molloy, Claire, Popular Media and Animals (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Swinney, Jacob T., First and Final Frames, online video recording, YouTube, 1 April 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6pMxLGgOzH8 [accessed 23/01/2019]

Tati, Jacques, dir., Mon Oncle (Gaumont, 1958)

Turvey, Malcolm, ‘Tati, suburbia and modernity’, in Screening the Paris suburbs: From the silent era to the 1990s, ed. by Derek Schilling and Phillipe Met (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018)