As a film which centers around a farming family, God’s Own Country is inseparable from animal life. Francis Lee sets the 2017 rural drama during the lambing season at a farm, thus crafting a display of the distress caused by animal breeding and the inevitable horror of animal death.

Customary to the Social Realist tradition, Lee depicts the harsh reality of farming in the lamb skinning scene, in which Gheorge cuts away the woolly coat of a dead lamb, to place onto another, in order for the lamb to be accepted by the grieving ewe. It is key to the Realist form that the scene omits a sentimental or emotional portrayal of the skinning, but instead illustrates this as an inevitable act.

Immersivity

The scene is a silent exchange between farmer and livestock, with the absence of non-diegetic sound highlighting the organic soundscape of the skinning. The crunching of bone and cartilage, when Gheorge manipulates the skin and cuts away the tiny limbs of the lamb, marries with his heavy breathing as he works quickly to complete the grim task. The immersivity of the scene is only furthered with the sole use of close-up shots of the procedure. These elements ensure that the audience is complicit in the process taking place within this isolated, wordless Yorkshire landscape.

Intimacy

It is this absence of dialogue, positioning Gheorge and Johnny on a closer level to the non-verbal animals, that creates a scene not just of immersivity but also of intimacy. This intimacy though is contradictory, as we must recognize that this is intimacy with a dead animal, further alluding to the disturbing characterization of the scene. Lee utilizes the single shot, focusing almost exclusively on Gheorge or the lamb, with over-the-shoulder shots mimicking his view of the lambs dismemberment. The scene refrains from exhibiting the lamb’s perspective of Gheorge, perhaps implying the prioritization of human life in the film, but also suggesting that in this film animal death is a finality. The intimacy of the scene is heightened by the method acting involved, as Lee states:

“I sent them off to work at local farms. Not to stand around and watch, but to do the shifts.

I knew from the start I never wanted a hand double or any fakery. So when you see Alec skinning a lamb, that’s Alec skinning a lamb.” [1]

Thus, there is a merging of performance with the actors real emotional response towards the skinning, whose experience informs their undertaking of the farmers paternal ‘cradle to grave’ responsibility. This is illustrated when Gheorge clothes the foster lamb in the coat, mimicking a parent guiding a baby’s arms through their sleeves.

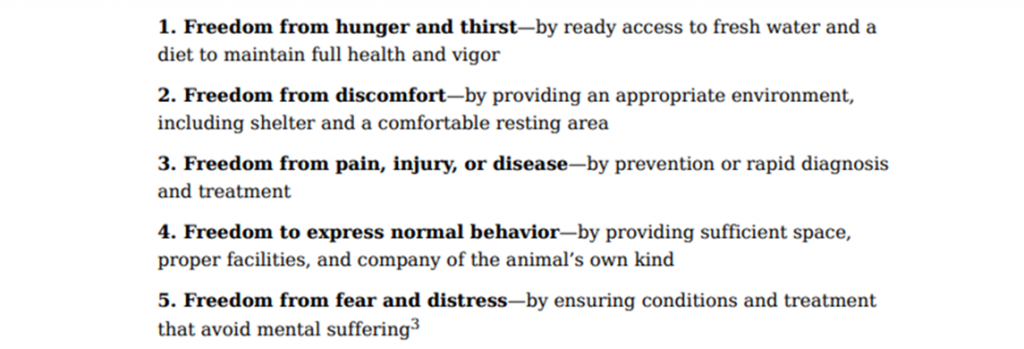

However, it must be noted that this style of realist film-making is complex in its relationship with animal ethics. In order to film scenes like these, an allegiance must be built with the actual site of animal brutality, in this case, a farm. So, while God’s Own Country emphasizes the precarious nature of animal welfare, it also maintains an alliance with the very industries which threaten animal freedoms. Below is the Brambell Committee’s report of 1965, which determined ‘Five Freedoms’ which are essential to animal welfare. We can thus consider whether forcing animals to carry a traumatic pregnancy truly prevents them from pain, injury, fear and distress.

The scene therefore, is one which highlights questions around the ethics of farming, as it displays an understanding of animal’s ability to adopt, build and maintain familial relationships, establishing a sentience which extends beyond their own individual needs. The scene also highlights how we as humans view motherhood in the animal world, holding mother and baby relationships to the highest level of compassion, as shown in the 2006 story of Larry, a lamb born in an abattoir, explained by Molloy:

‘Beneath the headline ‘Saved from the chop’ one paper described how none of the ten operatives at the facility had been prepared to slaughter the new-born lamb and her mother. The owner of the slaughter facility was quoted saying, “None of the lads would kill it – 10 lads all said no. No one was going to kill ‘owt like that. Both the lamb and the ewe are fit and healthy and everything has a right to live” [2]

This example further alludes to the overall significance of parental relationships in the film. Johnny and Gheorge adopt a paternal role over the animals on the farm. But, they also treat animals who are vulnerable due to pregnancy or childbirth more empathetically, which is indicative of the wider social treatment of animal mothers and babies as worthy of an extra level of compassion, as demonstrated in the story of Larry the lamb above. Thus, it is our perception of the vulnerability of animal babies and mothers which ensures our humanization of them, in turn leading to the deeper level of care and understanding they are treated with, within and outside of film. For example, we may consider the emotional response elicited by animal baby and mother relationships in other films, like Bambi (1942) and Dumbo (1941).

As a Realist filmmaker, Francis Lee reconstructs this emotional response, by presenting the death of an animal baby and the gruesome way in which the mother and baby dynamic is restored.

Filmography

Lee, Francis, dir., God’s Own Country (Picturehouse Entertainment, 2017)

Bibliography

ADHB Beef & Lamb, Late pregnancy and disease at lambing time: EBLEX telephone conference, Online recording of telephone conference, YouTube, 13 February 2015 <https://youtu.be/kYHMKKH5W0E> [Accessed 29 October 2021]

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002) ProQuest eBook

Molloy, Claire, Popular Media and Animals (UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) ProQuest eBook

Thompson, Paul B, From Field to Fork: Food Ethics for Everyone (Oxford University Press, 2015) Oxford Scholarship Online

Thompson, Paul B, The Spirit of the Soil: Agriculture & Environmental Ethics, Environmental Philosophies (Taylor & Francis, 1994) ProQuest eBook

[1] Patrick Gamble, ‘Interview: Francis Lee, dir. God’s Own Country’, Cine Vue, 29 August 2017 <https://cine-vue.com/2017/08/interview-francis-lee-dir-gods-own-country.html> [Accessed 11 November 2021].

[2] Claire Molloy, Popular Media and Animals (UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) ProQuest eBook (p.3).