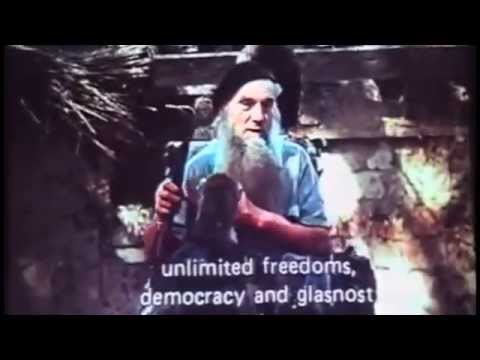

Vladimir Tyulkin’s Lord of the Flies (Tyulkin, 1990), shot in Kazakhstan on the eve of the Soviet Union’s fall, discusses imperial, social, and human fragility within the microcosm of ‘Grandpa’ Kirill’s yard. As Kirill states, “My yard is… a state in miniature… I look upon the numerous breeds of animals living in my yard as nations”. Kirill, formerly a criminal and the son of an enemy of the state, perpetuates the same fascist regime that fostered Stalin’s Terror. Though, instead of humans he subjugates animals: dogs, chickens, flies and their larvae, among others. Kirill turns the bodies of animals towards solving problems facing humanity, such as food shortages, by creating a self-sustaining national entity that relies on Kirill’s invention of the fly-trone. This contraption is a sarcophagus of larvae which are fed from the bodies of slaughtered animals, and reciprocally these larvae feed the living livestock. Tyulkin contrasts Kirill’s brutal engagement with animals as he both turns their bodies into fuel whilst discussing his passionate goals towards protecting his nonhuman populace, and his relationship towards former totalitarian leaders. As the film draws to a close, Kirill discusses his political goals, extrapolating the social functionality of the fly-trone whilst urging citizens of the Soviet union to begin building ‘fly farms’.

Tyulkin uses this ‘state’ to discuss a binary human/animal ontology and its contradictory nature, primarily by allowing the spectator to view the human, in Val Plumwood’s words, from the outside. [1] Through a nonhuman observer we witness the fragility of Kirill’s anthropocentric views as he ruminates upon human exceptionalism, the spiritual lack of animals, and his personal relationship to power. Lord of the Flies presents a mode of looking at the human, instead of looking through. The cinematic gaze of the nonhuman acts to destabilize the standard practice of cinematic identification as the sensorially personal view of the world is projected through the carnal body of a nonhuman. This sight is separated from the human being technically, as the camera is imbued with a unique physicality envisioning a separate form of sight through the manipulation of film stock and lenses. But, the physical nonhuman is also separated pro-filmically within the cinematic space.

The opening shots construct this nonhuman spectator. Though, as the camera takes on the subjective view of the fly, one must remember that this formal construction of nonhuman sight is inherently an extrapolated appropriation of assumed animal vision, which bears its own repercussions. Despite this, it operates so as to allow for a distinctive animal gaze, which is productive in itself. As the soundtrack begins, it is dominated by the fly’s wings and Kirill’s Balalaika. One other sound occurs as the fly nears a whimpering dog. The fly lands on Kirill, and the next shot is that of an enlarged, backlit fly, reminiscent of the ‘Demonic Beelzebub’. Even as the spatial relation between Kirill and the nonhuman coalesce, they remain disparate through this extra-textual separation. As Kirill’s monologue begins the camera oscillates between a close-up of his face, to that of the fly’s face. Here, the standard practice of the shot-reverse-shot becomes experimental as it establishes the nonhuman as cinematically engaged by insinuating conversation and animal cognizance through the use of film language. This introduction closes with the camera gazing up towards Kirill through a distorted lens that blurs the contours of the frame and degrades the camera’s sight, re-affirming the nonhuman physicality of it. The sequence introduces the world as sensorially proximal to the fly, both sonically and visually, and therefore outside the human’s perspective. The images and the accompanying soundscape enables the audience to recognise a being in possession of the apparatus that is cinematically spatially separate to the human, experiencing its own sensory autonomy, whilst encouraging an alignment with this subjective, nonhuman perspective alongside an external, analytical engagement with the human.

The Demonic Fly – Beelzebub.

This process of analysing the human through the gaze of the animal coincides with Val Plumwood’s writings. Plumwood, in being attacked by a Crocodile and in realising her ecological identity as physical prey, experienced a glimpse “from the outside of the alien, incomprehensible world in which the narrative of self has ended”. [2] This is in opposition to a ‘narrative of self’ that exists to “remake the world […] as our own, investing it with meaning, reconceiving it as sane, survivable”. [3] Through this external perspective, Plumwood viewed the surrounding world “from a place where human bodies and animal bodies exist in an indistinct zone of vulnerability and potentiality”. [4] This view displays the conceptualized human as subjective and fragile, whilst encouraging empathic understandings of human/animal unions so as to raise ethical questions of animal subjugation.

Lord of the Flies renders both of these views tangible. The audience, positioned ‘from the outside’ in the form of a nonhuman spectator, watches Kirill engaged in this phenomenological engagement with the world ‘from the inside’. Kirill’s perspective becomes incongruent as his thoughts contradict with his actions. For example, as Kirill is discussing where the inspiration for his ‘fly-trone’ began, after witnessing larvae writhing in a basin, he states that “our state is also a basin like this […] I thought about the year 1937, when a tyrant’s hand stirred the contents of the basin […] It’s a fascist ideology. One can’t live with such an ideology”. During this monologue, Tyulkin ironically cuts together shots of Kirill sifting larvae within a basin, his hands stirring their bodies. The following shot is an extremely long, wide angle, positioned above the body of Kirill amongst the roof-beams. Clearly, this is embodying the nonhuman watching Kirill as he pours boiling water over the larvae.

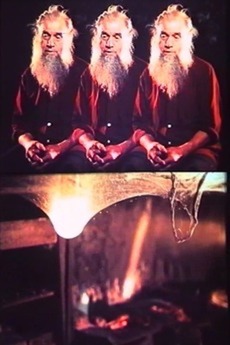

From this, the desperate delusion of Kirill’s self-narrative alongside his physical reality unfolds. [5] These moments of articulation appear opaque both vocally and physically within the confessional sequences in which Kirill sits before the camera, dressed and prepared for exhibition. This confessional sequence also invokes a religious engagement with the human, reminding us of the soul/body dualistic separation. Invariably, Tyulkin destabilizes this as Tyulkin fractures his image into constituent parts when he is most personally and cinematically aware. Kirill’s very physicality, the sanctified human body, becomes ethereal under scrutiny.

Kirill is fractured, as he looks towards his crematorium.

Within the dichotomous moments between the human self-narrative and the broader ‘outside’ view where humans accept an exposed ecological identity, Tyulkin engages with core binary oppositions between the human and the animal. When speaking from within his ‘crematorium’, Kirill says that “Now, dead bums can also be put into the lure. Why on earth not?” In suggesting that the homeless are not offered correct burial procedures, he recognises that they are outside the spiritually dignified realm of the human and that to be a ‘human’ one must operate within a socially defined space. This notion also acts as a premonition towards Kirill’s ultimate goals for his fly-trone. After an elongated, subjective shot of a fly circling the yard Kirill states that “I was a fly myself once, as a son of the enemy of the people”. These statements reveal that the category of the human is in fact demarcated by dominant social structures. Kirill inadvertently reveals “that the space of privilege secured for “the human” has never coincided with the boundary of the human species” (Original emphasis). [6] The categorical human and therefore the distinction between human and animal based on any logical level becomes unstable as it relates not to a species boundary but instead to a racialized and moralized construction perpetuated by dominant socio-cultural norms. Tyulkin, in engaging with Kirill’s past and in revealing the paradoxes of Kirill’s self-conceptualization, works to break down the human/animal boundary by revealing it as blurred, and fluctuant.

Because of this instability, Kirill must create the “ideal state in miniature” with himself as sovereign so as to trace a tangible human/animal boundary. Kirill perpetuates fascist governance similar to that employed under Stalin, and his yard becomes a proving ground for various intersectional practices. Sovereign Power operates alongside Foucault’s Biopower much as they did during the Soviet empire. [7] Through this, Tyulkin reveals the processes of oppression that create disparate zones of existence within the human category itself, drawing analogies to those that polarize the human and the animal. As Calarco states, in regards to anthropocentric practices concerned with the articulation of the human, “anthropocentrism’s […] characteristics are its recurring tendencies to institute and maintain sub- or extra- human zones of exclusion” and to employ various institutions to reproduce a privileged space for the human. [8] Within this space, Kirill establishes a form of exclusive inclusion, whereby separate extra-human and nonhuman zones are maintained so as to re-affirm the position of the human.

Kirill, the Soviet leader.

To do this, Kirill wields a visceral Sovereign Power, alongside disciplinary Biopower so prevalent under Stalin, to create specific types of subjects. He retains the right to kill, though always to benefit his state. Kirill slaughters chickens, cats, and dogs so as to create his lure, and subsequently destroys flies and larvae so as to cyclically sustain his populace. Panoptical sight is also prevalent, the process of establishing self-scrutiny when under constant gaze, through the symbolic presence of eagles within Kirill’s yard who are reminiscent of the Soviet NKVD. An emblematic animal of totalitarianism throughout history, as found in Nazi idolatry, the eagle is positioned as ever watchful and close to Kirill, at times being hand fed the flesh of slaughtered cats. There are multiple times when Kirill is positioned on a chair, with the animals circling his feet, vying for attention. Always in these moments the eagle is positioned aloof, sitting on the headboard of Kirill’s throne as it’s head mechanically scans the yard. This oppressive amalgamation of direct bodily violence and subtle social scrutiny are directly appropriated from the Soviet context and mapped onto the bodies of animals.

Tyulkin frames Kirill’s distinct brand of politics alongside intersectional comparisons, through the prism of the human/animal binary, so as to articulate what this means for the unstable category of the ‘human’ and the ethical questions of interspecies relationship raised therein. Through the prism of Kirill’s autocracy, Tyulkin constructs an articulate argument that does not attempt to raise the animal to the human through the employment of anthropomorphism which provides unstable ground for many empathic associations with nonhuman animals as humanist traits are read within the animal and mapped onwards to determine their anthropocentric value. Instead, he introduces the spectator to a potential perspective in which the human becomes not a species, but a category, and in which both human and nonhuman occupy a “space of exposed embodiment”. [9]

This exposure is drawn from Kirill’s subjugation under the same system he perpetuates and in his shared physical vulnerability, articulated through the fragmentation of his image and his perplexing contradictions of identity. From this shared existence, Tyulkin raises the ethical question that if fascism and violence are abhorrent acts, how can similar practices be redistributed within human and animal relationships and remain ethically sustainable in light of the fluidity of the human/animal boundary. If Homosapien beings fall outside of the category of the human, as Kirill once did (and does), where does the category of the human end, and the animal begin? Tyulkin reveals the moral schizophrenia evident within contemporary human/animal relations, and the underlying social structures that go into perpetuating such a union. [10] Through this methodology, Lord of the Flies discusses a way of re-distributing the human amongst the animals through the understanding of social, and subjective, structures that seek to oppress both formations of animality.

Footnotes:

[1] Plumwood, Val (2000), “Being Prey” [online text] Utne Reader, no. 100 (July-August 2000),

< https://www.utne.com/arts/being-prey.aspx> accessed 31 October 2015. pp. 3.

[2] Plumwood, Val (2000), “Being Prey” [online text] Utne Reader, no. 100 (July-August 2000),

< https://www.utne.com/arts/being-prey.aspx> accessed 31 October 2015. pp. 3.

[3] Plumwood, Val (2000), “Being Prey” [online text] Utne Reader, no. 100 (July-August 2000),

< https://www.utne.com/arts/being-prey.aspx> accessed 31 October 2015. pp. 3.

[4] Calarco, M (2014), “Being toward meat: anthropocentrism, Indistinction, and veganism,” Dialectical Anthropology, Vol. 38, no. 4: 415-429. PP. 427.

[5] Plumwood, Val (2000), “Being Prey” [online text] Utne Reader, no. 100 (July-August 2000),

< https://www.utne.com/arts/being-prey.aspx> accessed 31 October 2015. pp. 3.

[6] Calarco, M (2011), “Identity, Difference, Indistinction,” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 11, no. 2: 41-60. PP. 46.

[7] For a productive interpretation of the intersections between Biopower, Foucault, and the animal-industrial complex, please see:

Thierman, Stephen (2010), ‘Apparatuses of Animality: Foucault Goes to a Slaughterhouse’ [online text], Foucault Studies, No. 9: 91-110 (September 2010). < https://rauli.cbs.dk/index.php/foucault-studies/article/view/3061/3196>

[8] Calarco, M (2014), “Being toward meat: anthropocentrism, Indistinction, and veganism,” Dialectical Anthropology, Vol. 38, no. 4: 415-429. PP. 416.

[9] Calarco, M (2014), “Being toward meat: anthropocentrism, Indistinction, and veganism,” Dialectical Anthropology, Vol. 38, no. 4: 415-429. PP. 419.

[10] Taylor, C (2013), “Foucault and Critical Animal Studies: Genealogies of Agricultural Power,” Philosophy Compass, Vol. 8: 539-551. Pp. 525.

Bibliography:

Calarco, M (2011), “Identity, Difference, Indistinction,” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 11, no. 2: 41-60.

Calarco, M (2014), “Being toward meat: anthropocentrism, Indistinction, and veganism,” Dialectical Anthropology, Vol. 38, no. 4: 415-429.#

Plumwood, Val (2000), “Being Prey” [online text] Utne Reader, no. 100 (July-August 2000),

< https://www.utne.com/arts/being-prey.aspx> accessed 31 October 2015.

Taylor, C (2013), “Foucault and Critical Animal Studies: Genealogies of Agricultural Power,” Philosophy Compass, Vol. 8: 539-551.

Films:

Tyulkin, Vladimir (1990), Lord of the Flies.