“This is how you make dinosaurs?”

“No. This is how you play God.” [1]

Jurassic Park III revolves around the dinosaurs of the island ‘Isla Sorna’; genetically modified and inevitably abandoned in a previous movie of the franchise. It follows a wealthy family who have lost their son on the island, and try to pay their way out of the situation, deceiving people into helping them. Jurassic Park alumnus Dr. Alan Grant returns to the series, now famed for his previous involvement with the islands, and is tricked into helping Paul and Amanda Kirby find their son, Eric in exchange for research funds. Amongst a group of other hired aid, the characters end up stranded on the island, fighting for their lives against the dinosaur inhabitants whilst still trying to find Eric.

capitalism, particularly greed and commodification. Its message is less open to interpretation, and more of an explicit condemnation. The science-fiction adventure genre stylings, however, enable a presentation of these ideas in a more family friendly way. Jurassic Park III specifically examines the way capitalist society only cares for animals when they are able to be commodified; the dinosaurs were created as a tourist attraction, but after the events of the previous two films deemed the parks too dangerous to attract visitors, they were shut down and the animals left abandoned. However, this enticement of danger remains present in the wealthy; locals from nearby the island can be bribed into taking the rich on boat trips in surrounding waters. The greed explored throughout the film, albeit primarily at the hands of capitalism, also brings into question ideas of nobility and morality; raptor eggs are temporarily stolen but the reasoning behind the thievery is arguably honourable. Also worth noting is the direct theme of folly in the film; folly defined as ‘costly ornamental building with no practical purpose’ [2] is essentially a synonym for ‘Jurassic Park’. Perhaps most central to the plot of Jurassic Park III, though is a rapidly advancing science and technology, and what problems could arise from this combined with ideas of power in the not so distant future.

The film begins its set up on site at an archaeological dig, where the advancement in science, technology and knowledge is immediately introduced; the team are researching raptors intelligence, and on a visit to his old co-worker Dr. Grant excitedly pronounces ‘they were smarter than dolphins, they were smarter than primates!’ [3] This discovery comes after the raptors have been genetically engineered to life in the original film. The idea that we would play God before fully understanding what we were creating is key to understanding the animal ethics of the film. The greed of wanting to monopolise the entirety of an extinct species into a commodification is so profound that the entire objective is rushed to unsafe speeds. A well-researched, ethical engineering of animals with no basis of profit designed purely to learn would not have such negative and damaging results.

The sheer presence of the dinosaurs is an exploration of morals; they were shunned and isolated on the island by their creators. It stands that if humanity left them alone there to their own devices, a natural sense of balance and harmony could be found. However, humans still feel the need to infringe on the dinosaurs’ space. This is not a fictional or past issue; in contemporary society humans frequently invade the habitats of dangerous animals, act surprised when the animals try to defend themselves, and oftentimes end up killing the animal to save themselves. There is much to be said in the morals of leaving nature well alone; humans are not built to dwell in the sea, but still expect sharks and other potentially dangerous sea creatures to allow them to invade a habitat natural to its inhabitants, and unnatural to us. The primary plot of Jurassic Park III reflects this; the dinosaurs have been left alone to fend for themselves but the wealthy and inconsiderate still feel as though their entertainment is more important than the dinosaurs’ isolated wellbeing.

This isolation, though most likely the fairest way of cohabitation, is nonetheless abandonment. Scientists created the dinosaurs and cared for them until all of a sudden they didn’t. As their creators, they have a duty of care to ensure the dinosaurs’ wellbeing. Although the film shows this care cannot be direct for safety reasons, the dinosaurs are in a habitat not natural for them; the current state of the Earth is vastly different to how it would have been in the Cretaceous period. Being taken out of their natural habitat and state, in this case; extinction, presents the dinosaurs as akin to pets; they were bred for human entertainment and, upon disinterest or boredom, abandoned in a place strange to them. The cutting of the dinosaurs’ DNA with other creatures also gives a sense of desired domestication; the scientists did not want natural dinosaurs, they wanted altered versions easier to control; an anthropomorphised version of something almost entirely unhuman.

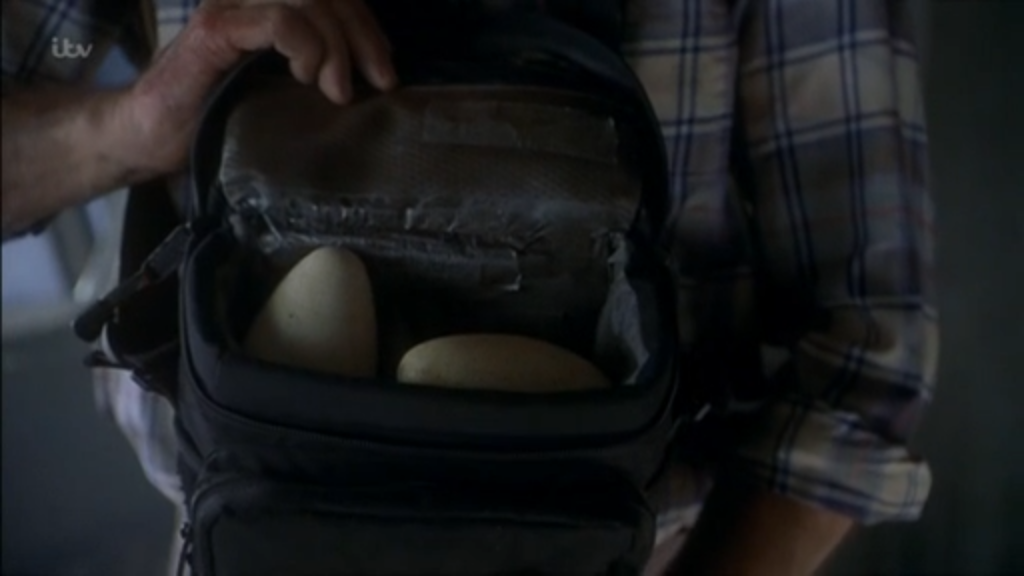

Raptors serve as one of the lead protagonists in the film, alongside a number of other types of dinosaurs. However, the reason the raptors are following and attacking the group is revealed in the third act to be a desperate attempt to get back their eggs.

Archaeology assistant Billy saw the eggs in their nest and stole some to sell on later for profit. The dinosaurs are seen as innately aggressive, attacking unprovoked, but an innate need to protect ones young is present in a number of natural species. The raptors were engineered, abandoned, and adapted to their situation to the point of breeding, when an unwelcome group intruded on their territory, and stole their young. The reasoning behind Billy’s stealing brings up important questions of morality, and moral ambiguity; he wanted to sell them for a profit he would use to keep the underfunded dig project going for another ten years. Though this may seem a noble cause, the commodification of unborn young for your own benefit over theirs is further proof of the hierarchical standing humans believe themselves to have over other creatures. Regardless of intentions, monetary value should not be applied to animal offspring; commodification from birth is an incredibly damaging practise, and deems profit as more important than wellbeing. As explored as a primary theme in Jurassic Park: The Lost World, the second movie of the series, these animals would undoubtedly be sold only to those who were wealthy enough; as we know the dig site is underfunded, we can safely assume that any group with the raptor eggs’ wellbeing in mind would not be able to afford to buy them. This leaves a small number of potential buyers; eccentrically wealthy people who would keep the raptors as pets, or military organisations who would militarise the raptors. This militarisation was later explored too in the 2015 spin-off sequel Jurassic World where raptors are trained under the guise of research and advancement whilst simultaneously being set up behind the scenes as soldiers. As Dr. Grant points out, ‘Some of the worst things imaginable have been done with the best intentions.’ [4]

One particular scene of the film’s third act stands out as a perfect summary of the dinosaurs’ commodification. It occurs whilst the group are trying to find a way off the island, having just escaped a Spinosaurus. After nearly falling off a rickety metal framework, Dr. Grant realises what they are in fact standing on is an enclosure. ‘It’s a birdcage.’ ‘For what?’ [5]

Grant’s description of the enclosure as a birdcage is conscious, and important; the creator of the park viewed the Pteranodon as essentially big birds. This demonstrates an immediate sense that the park creators did not know how to properly care for and house the dinosaurs, and instead likened each to a modern day pet or zoo exhibit they had somewhat more knowledge on; the bird cage held Pteranodon as bird exhibits, and the electric fence contained bigger dinosaurs as livestock. Though much of the film’s behind the scenes knowledge and planning refers to the cage as an aviary, Grant’s description of it as a birdcage negates this; he immediately deems it too small and constrictive to be the relatively freeing exhibition of an aviary. This brings about an important argument regarding animals in captivity, particularly when, as a by-product of their escape, the Pteranodons are seen freely flying over the island. Modern research suggests Pteranodons to fly akin to albatrosses; relying on wind speed near ocean surfaces. It also suggests their diet to consist primarily of fish. By this reasoning, it can be assumed, like albatrosses, that Pteranodons would not migrate away from an island that met all of their biological and dietary needs. For them to immediately upon release fly as far, fast, and high as they can presents the idea that they are taking their opportunity for freedom as soon as it comes to them; after the claustrophobic containment of the cage, they act as most trapped animals would and flee.

The Jurassic Park series has frequently brought into question ideas of animal ethics in regards to extinction; in later films, this is described by an antagonist as ‘extinct animals have no rights’. [6] This is a clear example of how the films all explore the idea of animals being underestimated; the dinosaurs are underestimated in terms of adaptability, intelligence, and rights. Dr. Grant and previous archaeologists and palaeontologists underestimated the intelligence of the raptors, the park creators underestimated the adaptability of the dinosaurs, and the genetics scientists underestimated the rights that should be granted the dinosaurs. This underestimation is directly responsible for all the negative events of the film and serves to examine the sense of entitlement humans believe themselves to have over every animal or person they deem lower than themselves. The entire concept of the ‘Jurassic Park’ relies on the cognitive dissonance of the people at the forefront of it; they describe the dinosaurs with only positive and respectful adjectives whilst simultaneously treating them as worthless, save for their monetary value or ability to bring in revenue. The inclusion of Paul and Amanda Kirby as wealthy parents is a conscious way of reflection. No care is shown for the boat operators killed when Billy became lost, and very little care is shown for Ben; Amanda’s boyfriend who took Billy to the island and was subsequently killed. Perhaps most conscious is their treatment of Dr. Grant; he is bribed with money his research desperately needs, his wish to not land on the island is entirely ignored, and he is punched for using his own experiences with the islands as evidence of why they should not be doing what they are doing. The treatment of Grant; ignorance, underestimation, and physical violence is exactly how the creators of the park treated the dinosaurs. This mirroring is subtle and shows the audience’s own disconnect between human ethics and animal ethics; we see the treatment of Dr. Grant as immediately cruel and wrong whilst simultaneously rooting against the presented antagonist status of the dinosaurs.

Jurassic Park III is clever. Though the lowest grossing and rated film of the franchise its arguments are perhaps the most eye-opening and clear. The narrative and character presentation makes the audience question a number of animal ethics issues; genetics, care, domestication, breeding, and hierarchy. The first film may have been most ground-breaking in its special effects, but the third is most ground-breaking in its ideas. By the end of the film, upon seeing the military presence and Pteranodon migration we are left rooting for the dinosaurs. Though they are surface-value presented as the villains, the film creates an important sense of sympathy for the animals and makes us question why we thought they were the negative to begin with; a lack of understanding being the precursor to misjudgement. It is perhaps the most animal-positive film of the franchise and makes no effort to excuse or present as positive any of the issues mentioned previously. It is a condemnation of entitlement and human zoo-culture and it serves as a very important reminder that although the dinosaurs and our treatment of them may not be real, animals that exist in the real world are still treated, or mistreated, in the same ways.

[1] Jurassic Park III, dir. Joe Johnston (Universal Pictures, 2001).

[2] Oxford Dictionaries, ‘folly’ https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/folly [Accessed 3 June 2018]

[3] Jurassic Park III, 2001.

[4] Jurassic Park III, 2001.

[5] Jurassic Park III, 2001.

[6] Jurassic World, dir. Colin Trevorrow (Universal Pictures, 2015).

Further reading:

Colin Trevorrow, dir., Jurassic World (Universal Pictures, 2015)

Don Shay & Jody Duncan, The Making of Jurassic Park (Boxtree Ltd.: London, 1993)

Michael Crichton, Jurassic Park (Arrow Publishing: London, 2015)

Steven Spielberg, dir., Jurassic Park (Universal Pictures, 1993)

Steven Spielberg, dir., The Lost World: Jurassic Park (Universal Pictures, 1997)

Bibliography:

Chapin, Sharon L. & Leslie D., ‘Biotech or Biowreck? The Implications of Jurassic Park and Genetic Engineering’, Bull. Of Sci. Tech and Soc., 14 (1994), pp. 19-23

Francione, Gary L. & Anna E Charlton, ‘The case against pets’, Aeon https://aeon.co/essays/why-keeping-a-pet-is-fundamentally-unethical [Accessed 3 June 2018]

Hutchinson, John, ‘Are Movies Science?’, University of California Museum of Paleontology, http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/buzz/popular.html [Accessed 3 June 2018]

Johnston, Joe, dir., Jurassic Park III (Universal Pictures, 2001)

McRobbie, Linda Rodriguez, ‘Should we stop keeping pets? Why more and more ethicists say yes’, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/aug/01/should-we-stop-keeping-pets-why-more-and-more-ethicists-say-yes [Accessed 3 June 2018]

Siegle, Lucy, ‘How ethical is a visit to the zoo?’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2008/may/04/ethicalliving.wildlife [Accessed 3 June 2018]

Tracey, Janey, ‘Five Ways Jurassic Park’s Velociraptor Differ from Their Real-Life Counterparts’, Outer Places, https://www.outerplaces.com/science/item/8974-all-the-ways-jurassic-park-s-velociraptors-differ-from-their-real-life-counterparts [Accessed 3 June 2018]

Weimerskirch, Henri, ‘Extreme variation in migration strategies between and within wandering albatross populations during their sabbatical year, and their fitness consequences’, Nature https://www.nature.com/articles/srep08853 [Accessed 3 June 2018]