The 2011 documentary The Whale confronts the moral and ethical struggle within intense human-animal interactions. While the film can be perceived as a cautionary tale about human interference in nature, there is no political statement being made to sway the audience. The leading affect within the film is sentimentality. Luna, the 2-year-old orca, is forced to turn to humans for comfort after being separated from his pod in Nootka Sound, British Columbia. As narrator Ryan Reynolds expresses, being lost in such a way “must’ve been like a child being lost in a supermarket” (2:07). While the many residents who were fortunate enough to interact with Luna on a personal level explain the experience to be otherworldly, others reckon these interactions are the leading cause of the whale’s demise. It is through Luna’s interactions with law enforcement as well as native residents that viewers are reminded that when humans perceive their own traits within an animal, sentiment overrules logic.

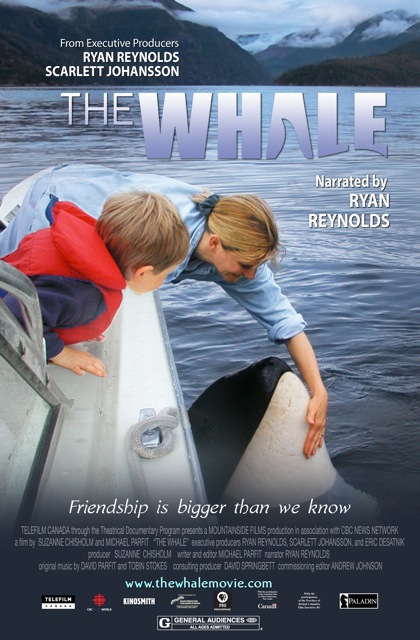

In The Whale, Luna acts like a small child, continuously making interactions comical by tail slapping, blowing bubbles, and playing with hoses and sticks. Due to this behavior, people humanize the whale, which becomes evident throughout the many interactions depicted in the film, including those between Luna and the local bureaucrats and residents. Michelle Kehler, one of the members of the Luna Stewardship Project, finds it extremely difficult to do her job when Luna gets in between the boats; Luna pushes Michelle’s arms away and pokes at her because he wants to play (56:29). This is a moment in the film where it becomes clear that sentiment overrules logic. Luna is a social mammal who practically begs for the attention it would naturally receive from its pod if it had one. Now, he has to turn to humans for family; however human regulation makes it very difficult to offer the animal the socialization it craves and needs to live. Therefore, being in a law-enforcing position becomes difficult: to a certain extent it is important to keep the animal safe by staying away, but the nurturing instinct of humans overrides the rules of the law to interact with the whale. While it might seem anthropomorphic, filmmaker “Parfit contends it is a legitimate way of understanding how Luna himself broke that barrier.”[1] As can be gleaned from the image below, Luna enters the lives of everyone he meets and makes it impossible for residents to refrain from having a once in a lifetime interaction with a killer whale. The human instincts for care and compassion intervene and it becomes clear that not even law enforcement has the right answer to how to keep the animal out of harms way.

The film’s trailer depicts an array of testimonies from residents, scientists, and law enforcement, who explain how there is no way to quantify just how unique interactions are with Luna. Humans have a tendency to attach human characteristics to animals in order to make sense of certain behaviors. Killer whales are known to lead emotional lives the same way humans do, which makes them even more susceptible to our anthropomorphization. The trailer makes the story personal for viewers who feel they are able to connect with the animal on an emotional level. From an early age, children imagine having fairytale relationships with animals, and so to have Luna himself break down the barrier between human and animal makes that fantasy a reality not only for residents of Nootka Sound but for audiences as well.

Throughout the film, there are many attempts made to figure out the proper steps to take to keep the whale safe. The Luna Stewardship Project keeps the whale under close monitoring in order to cut off human contact, but Luna continues to chase the boats. There is an attempt in the film to capture Luna and transfer him to a park, where he would live a life in captivity, but this transfer does not end up coming to fruition. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has concerns about attempting to reunite Luna with his pod because he has spent too much time away from them, which means there is little certainty that the other animals would accept him back into the pod. The director of the film explains, “The one thing that almost four decades of science has shown unambiguously is that Luna’s family of orcas (the Southern Resident Community) is intensely social and its members stick together for life.”[2] What this says is that if Luna had been reunited immediately after being separated, there is no reason why it would not have worked.

When Luna is left alone, he puts himself in harm’s way. It is clear that, for him, the safest place is in the arms of humans, but government officials believe this type of interaction to be highly life-threatening, since this puts Luna so close to boat propellers. There is a moment in the film in which a native resident, Jamie, lies on the edge of the dingy boat with Luna, who floats on his side, resting his head on the boat next to his human companion. Luna rests peacefully, longingly staring into Jamie’s eyes (1:03:52). The significance of this moment relates back to the notion of human sentimentality and the instinct to nurture a being with no family. Everyone wants what they believe is best for the whale. Laws can be passed and people can be thrown in jail; however, the whale’s life remains in jeopardy regardless. Here, giving a desperately lonely whale companionship overcomes ethical thought. The documentary consists of a war waged between residents who grow to love the whale as their own, tough-love government officials, and Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nations. The residents of Nootka Sound grow to build a relationship with Luna, feeling that the love they provide the whale is the only thing that will keep the animal safe. In contrast, the Vancouver ministry believes that the whale has become a detriment to society as well as itself; their job is to keep residents safe and Luna’s interaction with residents increases the risk of boats tipping over and the whale getting killed by propellers. The First Nations residents believe Luna–to whom they refer as Tsu-xiit, their deceased chief–is a reincarnation of their leader. They believe that everyone should let nature take its course rather than increase human intervention in the protection of the whale. Each of these groups believe that they have the whale’s best interests at heart; however the tension between them makes the life of the whale chaotic, as the groups constantly enter and exit his life.

The Whale presents a unique situation in which a highly intelligent and evolved creature places itself in the human world, rather than a situation in which humans force themselves into the animal world. The Whale ends with the death of Luna; he collides with the propeller of a tugboat. It is through bitter irony that this orca loses its life by colliding with a boat that it chases in order to find companionship to keep him alive. These moments remind the audience that, as humans, we cannot know what these creatures need or want. Regardless, when we can recognize ourselves within the animal and it asks for help, instinct and heart overcome logic and reason. Luna’s constant dependency on human connection conveys the idea that his love is fatal. The ugly truth is that Luna’s life remained in jeopardy regardless of laws implemented to keep people away. Whether he was kept in captivity away from the danger of boats or in the ocean with the companionship of people, without the support of a pod and a family of killer whales, there was no way to keep the whale safe.

Works Cited

Emily Tripp, ‘The Whale: Q&A About an Amazing Young Orca, Marine Science Today <https://marinesciencetoday.com/2013/03/05/the-whale-q-a-about-an-amazing-young-orca/> (2013)

IMDB, The Whale, <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1708537/?ref_=fn_al_tt_2> (2011)

Jason Barr, ‘Trailer and Poster for THE WHALE Produced and Narrated by Ryan Reynolds’, Collider, Trailer and Film Poster, 2011, <https://collider.com/whale-trailer-poster/>

Stephan Michaels, ‘Saving Luna documents lost baby killer whale’s struggle’, San Francisco Gate (2008) <https://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/Saving-Luna-documents-lost-baby-killer-whale-s-3230770.php>

The Whale That Adopted a Village, Defend Marine Mammals, Screenshot film image,

<https://defendmarinemammals.wordpress.com/2015/06/01/the-whale-that-adopted-a-village/> (2015)

[1]Stephan Michaels, ‘Saving Luna documents lost baby killer whale’s struggle’, San Francisco Gate, <https://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/Saving-Luna-documents-lost-baby-killer-whale-s-3230770.php> (2008)

[2] Emily Tripp, ‘The Whale: Q&A About an Amazing Young Orca, Marine Science Today, <https://marinesciencetoday.com/2013/03/05/the-whale-q-a-about-an-amazing-young-orca/> (2013)