The Shape of Water is a fantastical love story set during The Cold War about Eliza, a mute cleaner at a government laboratory, who falls in love with a hybrid amphibian-man who was captured from the Amazon by the film’s villain, Colonel Strickland. General Hoyt wishes to exploit the amphibian-man to Western advantage in the Space Race. Eliza and the amphibian-man develop an intimate friendship, but Colonel Strickland plans on vivisecting him, so Eliza and her friend Giles execute a rescue mission, assisted by Hoffsteller, a Soviet spy and scientist. Eliza and the amphibian-man have sex and fall in love, while Strickland searches for him. The tension builds as Hoffsteller is shot by the Soviets and Strickland pursues and shoots Eliza and the amphibian-man, who then heals himself and Eliza and kills Strickland. The film ends with Eliza magically acquiring gills and the couple embracing underwater.

The Shape of Water subverts the human-animal distinction in which The Human and The Animal are homogenised categories which are divided based upon absolute differences, as there are shown to be as significant differences between different humans as between humans and animals. [1] Eliza feels of the same nature as the amphibian-man, as they are brought closer through their mutual inability to speak. They form an intimate, sexual relationship, acquiring mutual understanding through looking and touching.

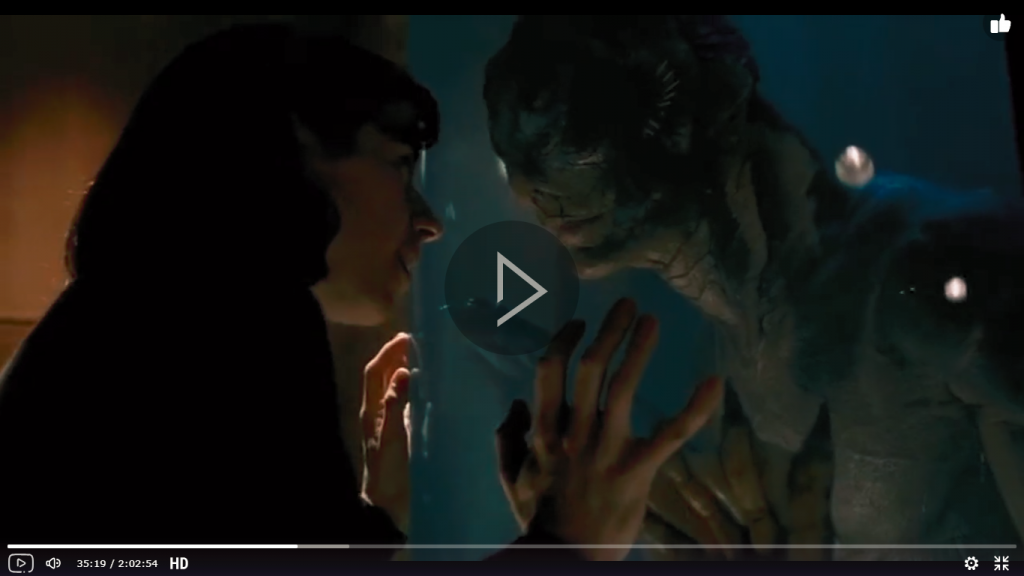

Language as a property which defines the human and is absent in animals is undermined, as Eliza cannot speak, but she and the amphibian-man communicate through sign-language, which is a not uniquely human form of language. The scene in which Eliza dances to a love song for the amphibian-man and then they touch one another’s hands through a pane of glass whilst gazing into one another’s eye; reveals how the species divide between them, as symbolised by the glass divide, is transcended through emotional connection. This suggests that their species difference is not a barrier to them falling in love, which is the film’s main message.

In this shot Eliza and the amphibian-man touch through a glass divide.

Eliza sees herself as of the same nature as the amphibian-man, expressed through her monologue scene when she asks Giles ‘what am I? I move my mouth like him. I make no sound, like him. What does that make me?’ [2] Eliza identifies with the amphibian-man due to their mutual inability to speak, implying that she is more akin to him than any humans. She twice refers to herself as what rather than who, which implies that she does not see a subject/object divide between humans and animals, but instead realises that she and the amphibian-man do not meet the requirements of The Human. Her speech is given extra weight, as she makes Giles repeat back what she signs, which highlights how important her message is. Contrastingly, Giles empathises their species difference from the amphibian man to disavow responsibility towards him, through asserting ‘it’s a thing, it’s a freak’ and ‘it’s not even human’. Giles dismisses ethical consideration towards the amphibian man through objectifying him as ‘it’ and ‘a thing’. Giles asks ‘does this mean that whenever we go to a Chinese restaurant you want to save every fish in the tank?’, which uses the culturally accepted killing of one animal species to justify allowing a human-animal hybrid to die. Giles implies that the amphibian-man is the same as fish in that as animals they are evidently not worth saving, implying that all non-humans have no ethical worth, while humans do. This question invites viewers to consider whether it is contradictory that we feel concerned about the amphibian-man’s impending death but would not were he a fish.

It is crucial that the amphibian-man is a human-animal hybrid, as Del Toro could not have created a love story that viewers would find romantic had he been purely amphibian. It is the amphibian-man’s unique hybridity which makes him appear wondrously otherworldly, as his bodily shape is human, but he has scales, gills, fins and webbed hands and feet, and can breathe in and out of water. His fascinating otherness is made possible by the fantasy genre, which means that the animal world can be represented as magical and otherworldly through creating an imaginary creature. When Eliza first meets the amphibian-man she passes him an egg, and he responds through hissing and flaring his gills, which expresses his anger and fear in animal terms, with the movement of his gills expressing his emotions. This sets up his characterisation as a wild creature who must be respected as such, not tamed or made human. This is made clear when the amphibian-man encounters the cat, as he crouches on all fours, hisses and flares his gills and then eats the cat, which reveals his predatory, animal nature. In response, Giles tells Eliza ‘he’s a wild creature. We can’t expect him to be anything else’ and does not condemn him. This reveals how Giles has learnt to respect the amphibian-man’s animality rather than using this to deprive him of ethical worth.

This shot depicts the amphibian-man as a wild creature – on all fours, with his gills flaring and his teeth bared, just before he attacks the cat.

Eliza and Giles do not attempt to humanise or domesticate the amphibian-man, rather Eliza’s relationship with him is equal, involving mutually respectful love. This is expressed in the scene where Eliza finds it remarkable that his skin lights up blue when touched, so gently strokes his skin. This is represented as caressing a lover, through their gaze upon one another which expresses mutual love, followed by the amphibian-man reciprocating and stroking Eliza’s neck, which is a pleasurable part of the body to be touched. The amphibian-man’s bodily response of emitting blue light is an otherworldly way to convey that he is emotionally and sensually responding without anthropomorphising him. This combination of recognisably human expressions of love with otherworldliness is possible because he is an imaginary creature, constructed through a combination of digital effects with a human actor, which is only possible within the fantasy realm. They acquire mutual understanding of one another’s sexual desire through look and touch, without requiring language. The way that they gaze into each other’s eyes and sensually touch one another expresses their budding love, meaning that their proceeding sex is presumed to be loving and romantic not bestial, as inter-species sex is generally considered to be. Their sexual intercourse is not represented as screen, making it seem more mystical and less carnal. The accompanying non-diegetic French ballroom music, which viewers associate with romantic unions, situates their sexual relationship within the romance genre.

This shot depicts Eliza stroking the amphibian-man who glows blue in response.

Framing their relationship within the genre of romance films encourages viewers to view them as deeply in love and to find this a heart-warming representation of how love can transcend all differences. In the following scenes Eliza dresses in red, including red heels, and smiles in reminiscence, which reveals how their relationship is sexually and emotionally fulfilling. Del Toro repetitively cuts between scenes of Eliza in her bathtub or boiling eggs, which are associated with her morning masturbation, to scenes of her feeding the amphibian-man eggs while he is in the water. This makes viewers consider how Eliza has transcended her mundane previous life, in which her sexual desire was merely another bodily requirement to satisfy, through transformative love. The sexual nature of their relationship is subversive, because viewers find it beautiful not bestial, meaning that species difference is shown to not be a ground on which to prohibit sexual contact and intimacy is established across species difference. However, their sexual relationship is only acceptable to viewers because the amphibian-man is part human, made possible by the fantasy genre, so inter-species sex is only condoned with one imaginary human-animal hybrid, not with real animals. This is because they both seem able to give informed consent, whereas animals are not regarded as able to give informed consent, because humans cannot know whether animals are choosing to engage in sexual activity with full knowledge of what it means to exercise this judgement. It is implied through the amphibian-man using sign language and establishing mutual understanding through looking and touching with Eliza, that he has the capacity to comprehend what choosing to sleep with Eliza means. So, although we do not see them express their consent, and this could not be through language, viewers presume that their sex is consensual as they both seem to have the capacity to make consensual judgments and they are in love.

The amphibian-man is not anthropomorphised but represented as a human-animal hybrid with a wild animal side, and the film ends underwater, an otherworldly space, with Eliza becoming more animal through acquiring gills and joining the animal world rather than the amphibian-man continuing to inhabit the human world of her house. This all suggests that Del Toro is exploring the human-animal distinction in its own right, not merely as a symbol for intra-human differences. This is also suggested through the variety of human-animal interactions explored: meat eating (within the discussion about saving fish from restaurants), pet keeping (of the cat), animals on television and the different ways that humans respond to the amphibian-man, with hatred, compassion or scientific interest. So, many ways of living with animals are explored, with expressing empathetic compassion being the most positive interaction represented. Eliza has experienced discrimination and so can feel herself in the amphibian-man’s position, and acts upon her emotional identification with him to save him. They both acknowledge their embodied existences as animals through their emotional and physical interaction, whereas Strickland rejects emotional response as weak, he desires to acquire dominance over the world and affirm his superiority as a privileged, white man.

This shot represents the amphibian-man gazing upon a horse looking at a newspaper.

The amphibian-man’s representation subverts normal conceptions of animals as not experiencing the world with intelligent understanding. Before eating the cat, he gazes upon the television, on which a horse is depicted as gazing upon a newspaper which says ‘Missile Scientist to send Horse on Flight’. This uses multiple levels of gazing to consider whether non-humans can intelligently comprehend what they gaze upon. The T.V audience laughs about the irony that a horse is looking at this headline as they presume that animals cannot understand language. Contrastingly, throughout the film viewers are encouraged to regard the amphibian-man’s gaze as expressing intelligent understanding, so viewers reflect upon what he may think about the horse. Del Toro combines close up shots of the amphibian-man’s face and eyes, (which imply his intelligent interaction with the world), with sequences of Eliza and the amphibian-man looking at one another, (in which their facial expressions reveal their mutual understanding), with the amphibian-man learning sign-language. Together, these representations suggest that the amphibian-man has intelligent understanding which he can communicate, which subverts the normative conception of The Animal as unknowable and unintelligent.

This close-up shot of the amphibian-man’s face in which he gazes up at Eliza, makes viewers reflect upon his emotions and thoughts. His facial expression conveys to Eliza his relief at being able to breathe properly again (as he has been out of water for a long time and has just got back into water).

In The Shape of Water, species distinction is not represented as a barrier to communication, as Eliza and the amphibian-man reach mutual understanding through being attentive to one another, and through looking and touching, which are implied to express emotions better than language can. This implies that animals’ inability to speak does not necessarily mean that they are inscrutable to humans and unable to communicate. The human-animal divide is subverted through the amphibian-man being cross-species, so individually bridging the divide, and through the intimate relationship established between Eliza and the amphibian-man. A sexual, loving relationship is the most intimate form of relationship possible, and Eliza feels more akin to the amphibian-man than any humans. So, rather than the human-animal distinction being an insuperable divide, it is overcome through mutual respect and bodily communication. The amphibian-man is represented as capable of intelligent understanding and communication and as forming a monogamous, romantic relationship, characteristics which are generally understood as human; but also as an otherworldly, wild creature who hunts and expresses emotions through flaring his gills and emitting blue light. This brings The Human and The Animal together in one body and implies that ‘human’ characteristics may not be exclusively human.

The Shape of Water uses an imaginary hybrid human-animal character which undermines the human-animal distinction, similarly to how Under the Skin destabilises the human-animal binary through using a trans-species protagonist Isserley. Their cross-species positions raise questions surrounding the human, who is hybrid in that humans are animals who assert their human superiority through externalising their animality onto The Animal. But rather than affirming her humanity through maintaining distance from the amphibian-man, Eliza recognises their shared nature and dissolves the divide between them through forming an intimate, sexual relationship. This subversive act both explores the human-animal distinction in itself and represents how all differences can be bridged through empathetic connection, and how difference should never be used to exclude certain people/beings from ethical consideration.

[1] I will use capitalised The Human and The Animal to represent the culturally constructed, general singular categories of The Human and The Animal, as oppositional, homogenised categories, as opposed to real-life humans and animals.

[2] The Shape of Water. Dir. Guillermo Del Toro. Fox Searchlight Pictures. 2017.

Bibliography

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002)

Calarco, Matthew, ‘Identity, Difference, Indistinction’, The New Centennial Review, 11.2 (2011), 41-60

– this essay explores three main theoretical approaches to the human-animal distinction, prioritising indistinction, which is relevant to how indistinction between humans and animals is created through Eliza’s sexual relationship with a human-animal hybrid.

Creature from the Black Lagoon. Dir. Jack Arnold. Universal Pictures. 1954

– this film is also about an amphibian-man hybrid and set during the Cold War, but it is a horror movie in which this creature is a monster.

Del Toro, Guillermo, Interview and Full transcript of Interview on the Shape of Water (2017) <http://www.goldderby.com/article/2017/guillermo-del-toro-the-shape-of-water-fairy-tale-sally-hawkins-richard-jenkins-complete-interview-transcript-news> [Accessed 16 May 2018]

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix, ‘Becoming-Animal’, in Animal Philosophy: Essential

Readings in Continental Thought, ed. by Matthew Calarco & Peter Atterson (New York: Continuum, 2004), pp. 182-210

– this explores how the human-animal relationship should be seen in relation to becoming/transformation rather than the human being a distinct identity, which relates to how Eliza becomes more animal, and the amphibian-man shifts between behaving like a wild animal and like a human.

Derrida, Jacques, ‘The Animal that Therefore I am (More to Follow)’, in Animal Philosophy: Essential Readings in Continental Thought, ed. by Matthew Calarco & Peter Atterson (New York: Continuum, 2004), pp. 231-261

– This explores human animality and the animal as the ultimate other, suggesting that the human-animal distinction involves disavowing human animality, which relates to the representation of difference and embodied human existence as animals in The Shape of Water.

Faber, Michel, Under the Skin (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2011)

– this book also undermines the human-animal distinction and explores how this relates to language and communication and uses an imaginary human-animal hybrid.

McKay, Robert, ‘A Dangerous Border’, Antennae, 8.2 (2008), pp. 60-64

– this explores inter-species sex and bestiality, suggesting that informed consent should be the ground to determine whether inter-species sex is ethically acceptable.

Pan’s Labyrinth, dir. Guillermo del Toro. Warner Bros. 2006

– this film is also a dark, fantasy, drama with fairy-tale elements which involves imaginary animals, but who are more monstrous.

The Shape of Water. Dir. Guillermo Del Toro. Fox Searchlight Pictures. 2017