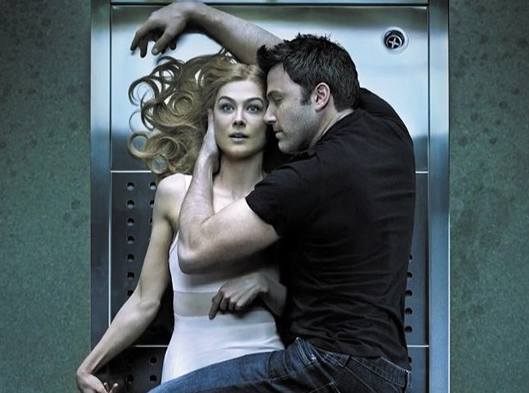

On the morning of his fifth wedding anniversary, Nick Dunne receives an unexpected phone call from his neighbour, who has spotted his indoor pet cat wandering outside the house. When Nick returns, not only does he discover that his cat has been misplaced, but his wife, Amy has disappeared too. Leaving a staged crime scene behind consisting of a seemingly heartfelt diary, a smashed table, and a carelessly mopped up pool of blood, Amy is believed to have been murdered, and her unfaithful husband is the likely culprit. With the help of a top lawyer, Nick uncovers Amy’s malicious plans, consequently shattering her attempts to frame Nick for her murder. In order to preserve her representation in the media as the victim and save herself from being sent to prison, Amy performs the brutal murder of her ex-boyfriend, whom she falsely accuses of rape. This permits her return to Nick, and the continuation of their toxic relationship is made obligatory.

Amongst Gone Girl’s intricate plot and immensely complicated protagonists who shift between hero and villain portrayals, the cat becomes an innocent bystander who reminds us of the artifice that is at play throughout the film. Although the cat is often overlooked as it serves a minor function in Gone Girl’s plot, it receives a considerable amount of screen time and exhibits an eerie, lingering presence in the scenes shot at the family home. The cat is significantly un-named, and not only is its mysteriousness appropriate when considering the film’s thriller genre, but it opens up discussions concerning its purpose in the film, and one interpretation is that it represents Amy Dunne. Having faked her disappearance, Amy is absent from present-day footage during the first half of the film, so the cat functions as a substitute for her character. Although the film is never explicit in the cat’s equation to Amy, both characters possess a similar unsettling presence in scenes, and when the animal’s recurring association with women is considered, this reading is confirmed.

Since antiquity, cats have been gendered feminine, and this tradition continues in the present day. As Katharine M. Rogers notes, the characteristics that are ‘simply natural in a cat’, such as mysteriousness, slyness and unpredictability, become ‘immoral’ when attributed to a woman.[1] Critics remain in dispute of Gone Girl’s reputation as a feminist or misogynistic text, for ‘although [Amy] is a cold-blooded murderer, she is evidently intelligent and spectacularly creative’, according to University Wire.[2] However, when the film’s animal elements are considered, Amy’s representation remains problematic because cats ‘signify maladjusted women’, according to Clea Simon.[3] Whilst Rogers argues that the cat/woman association ‘cannot be reduced to a mere vehicle for expressing misogyny’ (Rogers, p. 165), Amy’s embodiment of negative cat stereotypes, in addition to the horrific acts of violence she commits and the false allegations of rape she makes, contributes to the film’s misogynistic representation of its female protagonist. For this reason, Gone Girl is typical of its genre, because as Janina Falkowska and Sheri Chinen Biesen both declare, misogyny is ‘rampant’ in thriller films.[4]

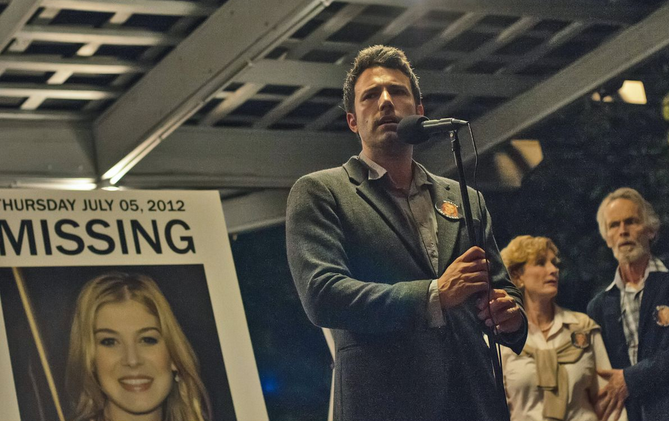

When the cat is first introduced to the film, we are unsettled by its presence, and we experience a sensation that is much like our encounters with Amy. In her analysis of Gillian Flynn’s original novel, Emily Johansen discusses the ‘uncanny, unsettling threats that seem, initially, to offer an explanation or justification for the crime at the heart of [the] novel’.[5] Whilst in the novel, the threats are ‘tied to current economic regimes’ (Johansen, p. 38), Gone Girl portrays the cat as its most uncanny threat, and when the cat’s equation to Amy is considered, there are misogynistic implications. During the police’s initial investigation of Nick and Amy’s family home, the cat makes a strange and unexpected appearance in the scene. As Nick opens the opulent double doors to the master bedroom, the camera suddenly cuts to an eerie medium shot of the cat on the bed, and its significance is further communicated when the camera peculiarly begins to zoom in on the animal.

The cat, although lying down, is sat upright and is therefore not passive, but exhibits an active presence in the scene. Considering its rigid body posture and its placement facing the door, we assume that the cat, disturbingly, has been expecting their arrival, and the animal is therefore portrayed not only as an autonomous individual, but a highly ominous one too, like Amy. The cat’s eerie autonomy and subsequent representation of Amy’s character is also implied through its eyeline matching with Nick.

The cat looks up at Nick in a cool and calculated manner, which is evidence of Amy keeping a watchful eye over her unfaithful husband and her domestic domain. Here, we are reminded that the cat was present when Amy staged the crime scene, so unlike Nick and the police officers, Amy and the cat know the truth, and the cat consequently emits an unsettling aura of sovereignty during the scene.

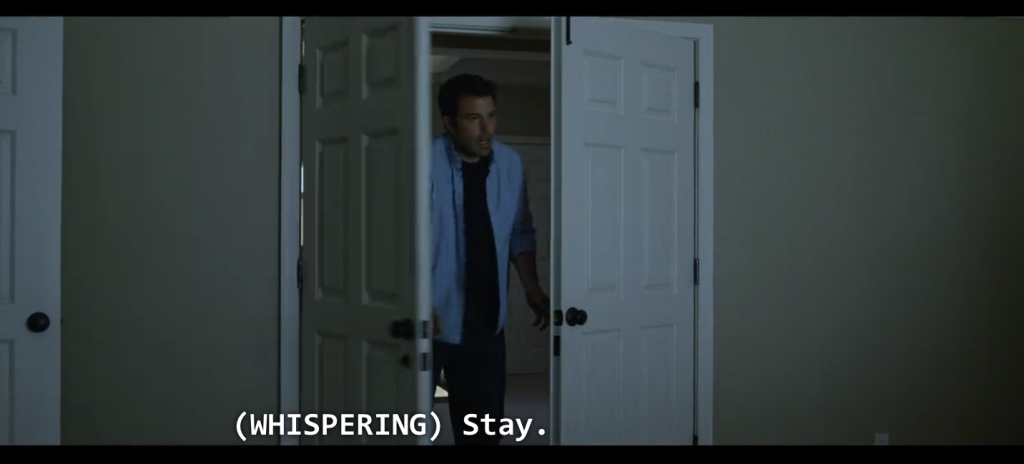

Amy’s projection onto the cat and the misogynistic implications this implies continue when Nick and the police officers leave the master bedroom to continue their investigation. Nick’s treatment of the cat during this scene is remarkably similar to a later scene depicting Amy’s first night back home. In the first scene, as Nick closes the double doors, he gazes down on the cat and orders it to “stay”, because like the audience, Nick is startled and disturbed by the cat’s appearance in the master bedroom.

The cat’s unreliability, hence Nick’s request for the cat to remain stationary, also reveals Nick’s anxieties concerning the cat’s movements, whilst simultaneously expressing his lack of trust in the animal. In a similar way, Nick refuses to sleep next to his wife when she returns, and his wariness of Amy is apparent when he leaves her bedroom and looks back over his shoulder to check that she has not moved.

His distrust is made even more explicit when he enters the spare bedroom. As he closes the door, still looking down the corridor in apprehension, the camera cuts to a hyperbolic zooming shot of the door shutting. The doorknob and keyhole appear centrally framed in an extreme close-up, and the diegetic sound of the door locking is heard.

This immensely stylised shot sequence that depicts Nick’s utter distrust of his wife equates to Nick’s demanding of the cat to “stay”, which similarly illustrates his uneasiness directed at the cat. As a result, Gone Girl advocates that women are untrustworthy and unreliable individuals, and this misogyny is reinforced through the film’s animal elements that project Amy’s character onto her husband’s pet cat.

In addition to Nick’s treatment of Amy and the cat, our investigation of the Amy/cat connection in these scenes is also encouraged by the scenes’ strategic placement in Gone Girl’s plot. There is a notable connection in terms of structure, because the first scene occurs on the morning of Amy’s disappearance, and the second depicts the evening of Amy’s return. For this reason, the cat replaces Amy in the first scene because she is missing, and the cat’s placement on Nick and Amy’s bed signifies its substitution for Amy’s character. The bed is a significant location for the continuation of a sexual relationship, and our knowledge of Nick and Amy’s crumbling marriage, in addition to Amy’s disappearance, suggests that the cat has taken Amy’s place. Further evidence of this is provided at a later point, when we see Nick stroking the cat, again in the master bedroom.

If we consider Marc Shell’s discussion of ‘petting’ as a synonym for sexual embracement, Nick’s replacement of Amy for the cat is confirmed.[6] Although this is a touching moment as Nick openly displays his adoration of the cat, there are misogynistic implications when Vogue‘s John Powers’s interpretation of the cat is considered. He understands the cat as an ‘emotional marker’ whose placement in scenes is strategic, manipulating our sympathies towards Nick or Amy.[7] This is problematic because whilst we are initially troubled by Nick’s infidelity to Amy, our sympathies are swayed in Nick’s direction as we witness his capacity to nurture and treat something with respect, and we never observe this behaviour in Amy.

Considering Powers’s interpretation of the cat in the one scene that Amy and the animal appear together, Powers’s argument remains insufficient because our sympathies do not lie with Amy. Instead, we are disturbed by Amy and the cat’s presence. Therefore, Johansen’s claim that Flynn’s Gone Girl’s threats are uncontainable and ‘remain untamed at the end’ (Johansen, p.39), can also be applied to Fincher’s movie adaptation. The scene occurs in the film’s final moments when Nick enters the kitchen and discovers his wife making pancakes for breakfast. The setting is significant, because the cat’s reputation as a domesticated animal parallels the stereotypical associations of femininity, hence Amy’s positioning in the heart of the domestic sphere – the kitchen. It is arguably the cat’s eeriest moment, and its equation to Amy remains problematic, consequently expressing a troubling level of misogyny. Like Amy, the cat is centrally framed, and it is alarmingly perched on the kitchen counter directly in front of Amy, like the pawn to its queen (Hello Giggles review).

Its elevation on the kitchen counters is un-natural, yet it effectively promotes the cat to a position of unsettling dominion alongside Amy. Both characters possess the same rigid posture, and the cat’s orange fur is likened to Amy’s golden blonde hair. The pair enact a fierce and judgemental glare at Nick, and the tense atmosphere is heightened when the cat begins to wag its tail. This is a sign of irritation, and it is directed at Nick.

Due to his appearances in close-up shots that depict his uneasiness, the audience relate to and sympathise with Nick, and our allegiances that already existed with him are strengthened. As a result, the film promotes a patriarchal bias whilst Amy and the cat, on the other hand, are condemned, and this disapproval is reflected in the cinematography during the scene. Unlike Nick, Amy and the cat rarely appear in clear close-ups, and when they do, the soft focus blurs their appearance, so Nick remains the camera’s focal point.

Furthermore, their backs are turned away from the camera, which inhibits our abilities to relate to the characters due to the camera’s placement and consequential concealment of the pair’s faces. Not only does this establish an emotional distance from Amy and the cat, but there is a physical distance too, hence their existence in long shots during the scene. At this moment, Amy and the cat are the epitome of danger, and Gone Girl’s misogynistic undertones are more apparent than ever due to the camera’s refusal to get closer to its female protagonist.

During the film’s crucial concluding moments, Amy’s depiction as a threatening, disturbing, and incredibly dangerous young woman is maintained, and her representation is both mirrored and intensified by the pet cat. Throughout the entire film, the cat exhibits an intimidating and domineering presence, and its mysteriousness requires interpretation. Whilst Gone Girl is never explicit in its projection of Amy’s character onto the cat, these final moments provide compelling evidence for its equation to the female protagonist, due to its placement alongside Amy which is not just physical but metaphorical too.

Gone Girl’s misogynistic portrayal of its female protagonist as a psychopathic and cold-blooded murderer is already problematic, but when her equation to the cat is considered, her representation becomes even more troubling. In addition to her unjustifiable acts of violence, Amy is a manipulative, unreliable and calculating individual, who therefore embodies the negative stereotypes that are associated with cats. As a result, we can be confident that the cat in Gone Girl evolves into a ‘vehicle for expressing misogyny’ (Rogers, p.165), which is a tradition witnessed across the cinematic form. Like Gone Girl’s cat, the cat in The Incredible Shrinking Man (dir. Jack Arnold, 1957) embodies a femininity so threatening that it has the potential to consume Scott who is shrinking and consequently experiencing an extended process of emasculation. Spiders often impose the same threat, which is evident when Scott encounters the lethal spider in the cellar, and Salt (dir. Phillip Noyce, Bradley Rust Gray, 2010) and Enemy (dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2015) are two more recent films that similarly use spiders to signify threatening women. Following this analysis of Gone Girl, we have witnessed the misogynistic implications of the cat’s existence in the film. Therefore, when films use animals to indicate disturbing women, we must remain wary of both the patriarchal and misogynistic potentials that the animals and the movies they feature in emit.

[1] Katharine M. Rogers, ‘Cats as Women/Women as Cats’, in The Cat and the Human Imagination: Feline Images from Bast to Garfield (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2001) pp. 165-185 (p. 165). Google Books.

[2] University Wire, ‘Feminism and Misogyny in Fincher’s Gone Girl’, University Wire, 18 October 2018 <https://search-proquest-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/docview/2124033095?accountid=13828> [Accessed 29 December 2018].

[3] Clea Simon, ‘A Cat of One’s Own’, in The Feline Mystique: On the Mysterious Connection Between Women and Cats (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2003) pp. 1-27 (p. 4). Amazon Book Preview.

[4] Janina Falkowska, ‘The Postmodernist condition in Post-socialist Eastern European Films’, in Postmodernism in the Cinema, ed. by Cristina Degli-Esposti (New York: Berghahn Books, 1998), pp. 131-143 (p. 135). Google Books.

Sheri Chinen Biesen, ‘Haunting Landscapes in “Female Gothic” Thriller Films: From Alfred Hitchcock to Orson Welles’, in Gothic Landscapes: Changing Eras, Changing Cultures, Changing Anxieties, ed. by Sharon Rose Yang and Kathleen Healey (Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2016) pp. 47-69 (p. 50). Google Books.

[5] Emily Johansen, ‘The Neoliberal Gothic: Gone Girl, Broken Harbor, and the Terror of Everyday Life’, Contemporary Literature, 57.1 (2016), pp. 30-55 <https://muse.jhu.edu/article/619446> (p. 38).

[6] Marc Shell, ‘The Family Pet’, Representations, 15 (1986), pp. 121-153 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2928394> (p. 125).

[7] John Powers quoted in ‘We Need to Talk About the Gone Girl cat’, Hello Giggles, 2014 <https://hellogiggles.com/reviews-coverage/need-talk-gone-girl-cat/> [Accessed 29 December 2018].

Bibliography

Biesen, Sheri Chinen, ‘Haunting Landscapes in “Female Gothic” Thriller Films: From Alfred Hitchcock to Orson Welles’, in Gothic Landscapes: Changing Eras, Changing Cultures, Changing Anxieties, ed. by Sharon Rose Yang and Kathleen Healey (Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2016) pp. 47-69. Google Books

Falkowska, Janina, ‘The Postmodernist condition in Post-socialist Eastern European Films’, in Postmodernism in the Cinema, ed. by Cristina Degli-Esposti (New York: Berghahn Books, 1998), pp. 131-143. Google Books

Johansen, Emily, ‘The Neoliberal Gothic: Gone Girl, Broken Harbor, and the Terror of Everyday Life’, Contemporary Literature, 57.1 (2016), pp. 30-55 <https://muse.jhu.edu/article/619446>

Powers, John, in ‘We Need to Talk About the Gone Girl cat’, Hello Giggles, 2014 <https://hellogiggles.com/reviews-coverage/need-talk-gone-girl-cat/> [Accessed 29 December 2018]

Rogers, Katharine M., ‘Cats as Women/Women as Cats’, in The Cat and the Human Imagination: Feline Images from Bast to Garfield (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2001) pp. 165-185. Google Books

Shell, Marc, ‘The Family Pet’, Representations, 15 (1986), pp. 121-153 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2928394>

Simon, Clea, ‘A Cat of One’s Own’, in The Feline Mystique: On the Mysterious Connection Between Women and Cats (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2003) pp. 1-27. Amazon Book Preview

University Wire, ‘Feminism and Misogyny in Fincher’s Gone Girl’, University Wire, 18 October 2018 <https://search-proquest-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/docview/2124033095?accountid=13828> [Accessed 29 December 2018]

Further Reading

Billson, Anne, Cats on Film <https://catsonfilm.net/>

Burkeman, Oliver, ‘Gillian Flynn on her Bestseller Gone Girl and Accusations of Misogyny’, The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/may/01/gillian-flynn-bestseller-gone-girl-misogyny>

Cox, David, ‘Gone Girl Revamps Gender Stereotypes – For the Worse’, The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2014/oct/06/gone-girl-female-stereotype-women>

Creed, Barbara, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, 1st edn (Abingdon: Routledge, 1993)

Desjarlais, Stevie K. Seibert, ‘Disappearing Wives: Interchangeable Women and Their Radical Escape in Le Bonheur and Gone Girl’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, (2018) <https://doi.org/10.1080/10509208.2018.1465373>

Mayer, Sophie, Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema (London/New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2016) DawsoneraPark, Ae-kyu, ‘The Cat: A Symbol of Femininity’, Journal of Symbols and Sandplay Therapy, 6.1 (2015), pp. 43-61 < http://e-jsst.org/upload/jsst-6-43.pdf>

McDermott, Jim, ‘Marriage, Violence, The Synod and Gone Girl, America Magazine <https://www.americamagazine.org/content/dispatches/marriage-violence-synod-and-gone-girl> Orman, Stephanie, “What a Perfect Monster!” Gone Girl’s Destablization of Feminine Archetypes in Popular Media’, (2016) <http://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/scholar/items/show/41>

Rogers, Katharine M., Cat (London: Reaktion Books, 2006)