Glen Morgan’s disturbing horror film Willard portrays the life of social misfit Willard Stiles (played by Crispin Glover), and a colony of trained rats who live in the basement of his somewhat derelict mansion. Whilst at first Willard intends to dispose of the rodents, he instead connects with a distinctive white rat whom he names Socrates and later considers to be his “best friend”. Unlike most who would be disgusted by the presence of rats in the home, Willard treats them as allies and seeks revenge using the trained rodents through his almost telepathic connection with them. The film takes a dark turn after his boss shockingly beats Socrates to death at work, leading Willard to brutally instruct the rats to murder him. The driving force of horror in the film is the abnormally large and ‘evil’ rat Ben who turns against Willard and leads the colony in an attack against him, ultimately resulting in Willard killing Ben and being placed in a mental institution.

As a horror film and remake of the original Willard (1971),[1] the film is incredibly gothic in style and features many typical characteristics of the genre such as a decrepit mansion, a doomed romance, and a pale oddball title character who is an obsessive social anomaly. The gothic is illustrated throughout the film using stylised visual effects, with chiaroscuro lighting often used in scenes to exaggerate the horror and dangerous atmosphere which Ben often instigates. These dimly lit scenes in the basement mirror the habitat of the rats who would ordinarily live in dark and dingy sewers and pipes, reminding us as an audience that rodents (particularly wild rats) do not belong in the home. Whilst the film is not particularly frightening, horror is portrayed through the discomfort and unpredictability of the protagonist’s relationship with the rats and the tension that this creates. The scariest character of the film however is the abnormally large rat Ben, whose mere presence creates a sense of trepidation and fear. Ben along with his fellow rat colony create horror within the film both because of their evil desire to fulfil Willard’s violent attacks but mostly because of the later power shift which leaves Willard defenceless in comparison to Ben and his colony of rats.

Within Willard, there are two very opposing representations of rats. Socrates, the sleek white rat whom Willard regards as his favourite is deemed by him to be inherently good with a moral conscience, unlike Ben who is large, brown, and disliked. Although he names and talks to both animals as though they can understand him, Willard treats them differently, both in his handling of them physically and in his attitude towards them. Socrates for example is often held or positioned near to his face on his shoulder or in his breast pocket, whereas Ben is often roughly handled such as being held by his tail or thrown down the stairs into the dark basement. Willard’s handling of Ben portrays the rat as an unwanted wild rodent who is unlikeable, contrasting with Socrates who is anthropomorphised and domesticated who seemingly understands Willard’s thoughts and emotions like a ‘best friend’ would. The differing treatment between the two rats singles Ben out as savage in comparison to Socrates who has the somewhat equivalent of a human relationship with Willard, which influences our perspective of Ben too. Although the animals were both at first equally unwelcome in the basement of the house, Socrates is welcomed due to his resemblance of a pet rat, unlike Ben who represents a wild and dirty rodent commonly associated with rats. The colour of the two character’s furs symbolise the qualities that Willard attributes to them; white equals innocence whereas brown is synonymous to dirt.

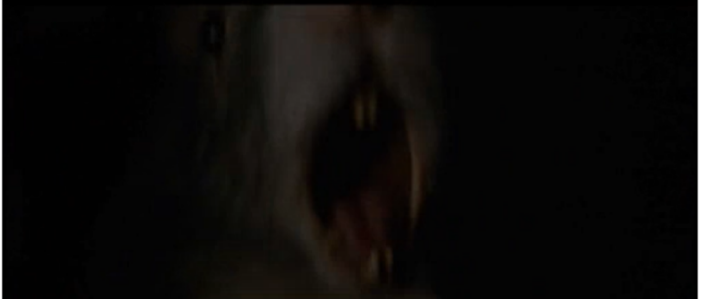

After Ben’s repeated dismissal from Willard his evil side reaches its peak at the end of the film, once Willard flees to the attic of his house to avoid the attacking rats. Despite the difference in strength and size between the human and the animal, Willard is portrayed as weak and defenceless in comparison to Ben’s wrath. The shift from a tracking shot following Willard’s run from the rodents to the abrupt static shot once he meets Ben demonstrates the violence and fear that he radiates and the sense that the rat is in control, both of Willard and over us as an audience viewing through the camera lens. The shot of Ben facing Willard at eye level through the bars at the top of the staircase creates an image of Willard as imprisoned, the cinematography symbolically portraying Ben’s dominance as a rodent over the human; Ben is the prison guard. A short close-up shot of Ben’s blank primal gaze as he watches Willard shows that he has no sympathy or remorse for Willard and highlights that he does not have the moral conscience that was attributed by Willard to Socrates. Willard’s pathetic whisper, “Ben, I thought we were friends” further emphasises the rat’s power due to the absurdity of a human begging a rodent for mercy. Jump cuts showing close-up shots of Willard’s blood-stained hands clinging to the railing whilst Ben attacks him unforgivingly further cements Ben as wild and truly animalistic.

The scene is highly reminiscent of The Lion King,[2] where Scar forces Mufasa off a cliff into a running herd, captured through a slow-motion fall which is very similar to the shot of Willard’s fall from the staircase. This similarity between lion and rat suggests that despite Ben’s species and size, he is as vicious and dangerous as a predator from the top of the food chain. This is particularly symbolic as the rat is positioned at the top of the staircase in the attic, so he is literally superior to Willard within the house. Another interesting point to note is the difference in the two character’s falls, as Mufasa falls to the sound of his son’s scream, whereas Willard is completely alone with nobody to mourn him. The sound shift from a suspenseful non-diegetic string instrument score alongside the unnerving sound of scuttling of rats, to sudden silence with only an audible gasp whilst Willard falls creates a really jarring moment in the film which exaggerates his loneliness and the finality of Ben’s dominance.

An argument which is applicable to Ben’s character is a comment from Animal Horror Cinema, ‘the shark in Jaws is not portrayed as more dangerous because it behaves in a way that is not natural for its species, but because it also becomes more like a human. It has a reason to kill and seems to be driven by a desire for revenge’. [3] This notion that the horrific behaviour of an animal is due to human-like qualities can be easily compared to Ben, who despite having no dialogue or anthropomorphic characteristics (excluding his human name), is portrayed as inherently evil because of his ‘plotting’ for revenge. Although rats are known to occasionally attack humans, Ben undoubtedly has a human ability to plan ways to make Willard suffer, portrayed through filmic techniques such as close-up shots of his head in dark settings which exaggerate his ‘evil’ thoughts. Despite our inability to truly understand his character due to his lack of dialogue, his intentions are made obvious through shots of his watchful eyes and his refusal to follow Willard’s orders unlike the rest of the colony.

This portrayal of Ben’s desire for revenge is conveyed through the significant positioning of camera angles and lighting throughout the film as the cinematography captures the rat’s capabilities and deceptiveness. Jonathan Burt’s statement, ‘Communication by the look […] has a different set of implications because it can be seen to be more primal and perhaps also telepathic’, [4] demonstrates the reason we perceive Ben as thinking ‘evilly’ in these shots. The close-up shots of his eyes/face appearing to be watching scenes around him whilst cast in dark lighting creates the sense that the animal is imagining dark thoughts. Even though it is us as an audience who attributes the rat as able to think evil thoughts, the eerie tone of the score, gothic lighting, and focus upon Ben’s eyes creates the sense that he is wicked with a higher intelligence than the other rodents in the house.

This technique is used during the death of the cat scene, where Ben watches the cat struggle from above as it looks for a way to escape the colony of rats attempting to catch it. A zoom shot shows the cat and then cuts to a zoom shot of the hole, visually creating a sense of time pressure for the animal to decide whether to jump which builds tension. Once the cat attempts to escape, Ben appears from the darkness and attacks the cat forcing it to fall to its death in a sea of rats. The quick succession of close-up jump cut shots from Ben’s teeth bared, to the cat screeching back, to Ben attacking the cat and to its fall occur so quickly that Ben’s violence is particularly shocking and unexpected. The final shot of the sequence is

another zoom shot taken from a low angle of Ben licking his lips as he watches the cat disappear under rats, cementing his character as evil, bloodthirsty, and especially menacing as he watches the carnage from above. This low angle shot creates a visual sense that he is an untouchable power, not only over the rat colony but also foreshadowing his later dominance over Willard.

Ben’s dominance over the household of rats and especially over Willard cements him as calculating and intelligent. Although Willard attributes Socrates as being the rat with human-like understanding, it is Ben who is observant and formidable with an ability to over-rule a human. The quote from the New York Times, ‘Willard teases you before each rodent invasion with squeaking and scuttling sound effects from the unseen hordes’ describes the film perfectly.[8] The close-up shots of Ben’s face tease us as an audience to try to understand what he is thinking or plotting, which paired with the non-diegetic sound of rats acts as both a tool to build suspense as well as to further emphasise the power he has within the household. He is often shot in dark settings adding to the gothic and tense nature of the film which is regularly seen in other portrayals of ‘bad guy’ animals in cinema, such as Rat from Fantastic

Mr. Fox[9] and Ratigan from Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective,[10] both of whom are similarly large and brown with distinctive eyes. It is important to note that as a society we identify dark tones as bad, which is why antagonists are commonly presented in this way in film and literature. This highlights the reason that the colour of Ben’s fur is so significant in the film as it is what dubs him as a wild rodent, contrasting with the white rat Socrates who is almost worshiped and adored by Willard perhaps due to his pet-like appearance. It is the darkness that Ben represents and is often portrayed in which makes him so frightening.

This stark contrast in appearance between the two rats also further differentiates the good versus evil which they represent as characters, despite both animals being initially unwanted rodents who broke into the same home. Whilst Socrates is placed on a pedestal by Willard for his so-called intelligence, Ben is the animal who reflects the gothic mansion and the reality of Willard’s life as a social misfit. Ben as a character is portrayed as truly evil through his watchful eye over the violence which he conducts, with close-up shots often capturing his primal gaze. Despite his violent animalistic qualities, he is still portrayed as having a human-like intelligence due to his ability to plot and seek revenge. His character is truly evil and is what makes the film so unsettling for viewers to witness, especially with a pre-existing dislike of rodents.

Further reading:

Stephen Prince, The Horror Film (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2004)

Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002)

ScreamFactoryTV, Willard (2003) – Clip: Chewing And Entering, online video recording, Youtube, 11 February 2019, <https://youtu.be/6VJCf0r0W_A> [accessed 14 January 2021]

References:

[1] Willard, dir. by. Daniel Mann, (Cinerama Releasing Corporation, 1971).

[2] The Lion King, dir. by. Roger Allers, Rob Minkoff, (Buena Vista Pictures, 1994).

[3] Katarina Gregersdotter, et al (eds), Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, history, criticism, (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015), p. 213. ProQuest Ebook Central.

[4] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion, 2002), p.41. ProQuest Ebook Central.

[5] Stephen Holden, ‘FILM REVIEW; Rats, Rats Everywhere, and Nary a One That Won’t Gnaw Your Horrified Heart’, New York Times, 14 March 2003, <https://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/14/movies/film-review-rats-rats-everywhere-nary-one-that-won-t-gnaw-your-horrified-heart.html> [accessed 12 January 2021].

[6] Fantastic Mr. Fox, dir. by. Wes Anderson (20th Century Fox, 2009).

[7] The Great Mouse Detective, dir. by. John Musker, Dave Michener, et al. (Buena Vista Distribution, 1986).

[8] Stephen Holden, ‘FILM REVIEW; Rats, Rats Everywhere, and Nary a One That Won’t Gnaw Your Horrified Heart’, New York Times, 14 March 2003, <https://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/14/movies/film-review-rats-rats-everywhere-nary-one-that-won-t-gnaw-your-horrified-heart.html> [accessed 12 January 2021].

[9] Fantastic Mr. Fox, dir. by. Wes Anderson (20th Century Fox, 2009).

[10] The Great Mouse Detective, dir. by. John Musker, Dave Michener, et al. (Buena Vista Distribution, 1986).

Bibliography:

Allers, Roger, Minkoff, Rob, dir., The Lion King, (Buena Vista Pictures, 1994)

Altman, Rick, Film/Genre, (London: BFI, 1999), Bloomsbury Collections All Titles

Anderson, Wes,dir., Fantastic Mr. Fox, (20th Century Fox, 2009)

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion, 2002), ProQuest Ebook Central

Ebert, Roger, ‘Willard’, rogerebert.com, <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/willard-2003> [accessed 12 January 2021]

Gregersdotter, Katarina, et al (eds), Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, history, criticism, (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015), ProQuest Ebook Central

Holden, Stephen, ‘FILM REVIEW; Rats, Rats Everywhere, and Nary a One That Won’t Gnaw Your Horrified Heart’, New York Times, 14 March 2003, <https://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/14/movies/film-review-rats-rats-everywhere-nary-one-that-won-t-gnaw-your-horrified-heart.html> [accessed 12 January 2021]

Mann, Daniel, dir., Willard, (Cinerama Releasing Corporation, 1971)

Michener, Dave, Musker,John, et al. dir., The Great Mouse Detective, (Buena Vista Distribution, 1986)

Morgan, Glen, dir., Willard, (New Line Cinema, 2003)

ScreamFactoryTV, Willard (2003) – Clip: Packed Kitchen, online video recording, Youtube, 11 February 2019, <https://youtu.be/dNFv93uxHek?t=90> [accessed: 15 January 2021]