How are human-animal relationships redefined when the lines dividing their respective humanity and animality are warped for scientific advancements? Director Jon Hess explores these altered dynamics within the 1988 science fiction horror film Watchers. When a devastating fire rips through the Banodyne Research Laboratories, the ongoing chaos is manipulated into an escape by two genetically-engineered rival creatures; one, the OXCOM, a grotesque, humanoid combat animal with violent impulses, and the other, a golden retriever with human intelligence. After running to a nearby suburban area, the dog, in an effort to flee the OXCOM’s attempts to kill him, hides in teenager Travis Cornell’s truck. Once discovered, the dog’s uncanny human-like awareness impresses Travis enough to keep him. Affectionately dubbed as ‘Furface’, the dog and Travis, as well as his mother Nora, grow closer through their understanding and compassion for one another. While this new family is being forged, however, the OXCOM – with its equal human mentality – has been stalking the town, brutally murdering anyone that comes between it and its goal of destroying the dog. This leads to a climax where the Cornells, having been chased from their home, are forced to a remote cabin where they must protect Furface from his monstrous counterpart in order to preserve their peculiar family unit.

Figure 1: Trailer for Watchers

By prioritising the bond between the dog and Travis, the film grounds its innovative science fiction and horror elements within a traditional canine companionship narrative. The hybridisation of these genres – reflecting the natures of Furface and the OXCOM – allows the human-dog relationship to surpass mere mutual alliance and pet ownership, and instead evolve to a stage where both species cultivate a true understanding of the other’s interiority. This is reinforced through the framing, angles, and shot composition, with these techniques not only emphasising Furface and Travis’s extraordinary dynamic, but also signifying the dog’s transition from Man’s Best Friend to Man’s Intellectual Equal.

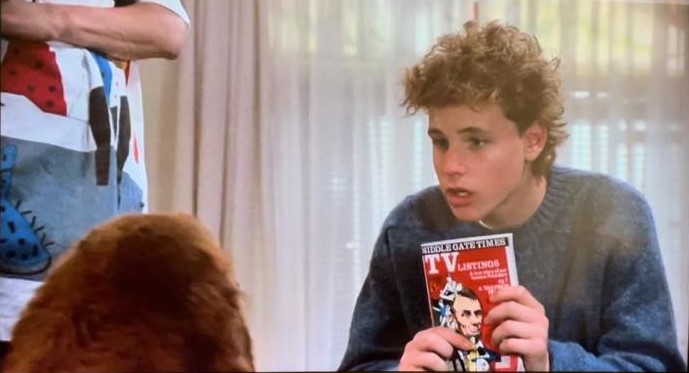

The playful interplay between Furface’s canine qualities and his human consciousness assists in the film’s consideration of a broader concept of Otherness within humanity. Although dogs have been regarded throughout history as a companion species to humans, it is only through Furface’s engineered nature that opposing aspects of ‘human’ and ‘non-human’ are reconciled. The film’s focus on his amalgamated animal exterior and human interior allows him to function as an extension of humanity, whilst also not sacrificing his biological identity as a dog. This is demonstrated when, in an effort to convince Nora that Furface can truly understand “everything we’re saying”, Travis prompts his mother to test the dog; initially through asking him to physically associate a word with the correct picture on a choice of two magazine covers, and then by barking either once for “yes” or twice for “no” in response to questions. Throughout the quizzing, the camera alternates between close up shots of the characters whilst they are speaking. Though Furface does not always bark during these moments of singular focus, he is still afforded lingering shots that both emphasise his canine appearance and capture his answering facial expressions.

By doing this, the camera signals that he is as much an active participant in the conversation as the human characters, though a ‘silent’ one. This form of ‘dialogue’ entices the audience to imagine his responses, consequently developing their own intellectual connection with the dog. Through these elements, while his bond with his newfound family can be deemed an interspecies relationship, it is ultimately through Travis and Nora’s – as well the camera’s – conscious acknowledgment of his similarities and differences that Furface is transcended into a position of human Otherness. This categorisation empowers the dog, enabling him to be perceived as a true intellectual equal. The correlation between his Otherness and mental abilities is reinforced through the positioning of the characters within the shot.

During the more generalised queries, Travis and Nora stand above the dog, occupying the upper portion of the frame while Furface remains in the lower third. Once the dog has demonstrated his “genius”, Travis changes to a much more specific line of questioning by requesting Furface identify, by barking in response to a name, which president is pictured on the magazine. While doing this, Travis sits down, lowering himself in the frame till he is equal level with Furface. Through this arrangement, the film not only indicates the similar mentalities between Travis and Furface, but also, as evident through the dog’s knowledge of US presidents, that they are capable of sharing a human culture with each other. Furface therefore, unlike other dogs, does not just exist within human spaces, but is capable of fully participating in them in a way that harmonises with established humanity. As a result, his Other mentality and behaviours allows him to assume the role of a true intellectual equal to not just the Cornells, but all humans.

Figure 7: Furface Typing on a Computer

It is through some of Furface’s unusual methods of communication that the film is able to not only illustrate his and the human characters’ shared intellect, but also connect it with his inclusion into the Cornell family – and by extension, humanity. Although he often relies on barking in response to questions, there are several instances where he adopts exclusively human practices in order to convey more complicated messages. In Jonathan Burt’s Animals in Film, he stresses that “the degree to which humans and animals are alienated from each other is sometimes gauged by the extent to which some form of natural communication is or is not possible”.[1] By ‘performing’ his human identity in these ways, Furface is able to foster a more mutual means of interaction that bridges the gap between his and Travis’s species, resulting in the development of a genuine understanding and familial bond between the two.

This is evident during two scenes where, after being forced to take refuge in the cabin, the dog uses tiles from the boardgame Scrabble to initiate two different yet related conversations with the teenager. During the first instance, Travis returns to the cabin to find Furface waiting for him in front of the open boardgame. As the teenager lowers himself to the dog’s eye level to read the tiles, the camera tilts downwards, framing both them and the Scrabble board from a high angle as Travis recites Furface’s warning; “I STAY U DIE”. This shot is further unbalanced by the positioning of Travis during his close ups, with the extreme leaning of his head to one side contrasting against Furface’s centralised placement. These elements of disorientation accentuates the dog’s tragic choice between either endangering Travis’s life or sacrificing all connection to him. As the dissolution of their familial bond would alienate Furface from humanity, this would consequently threaten his position as an intellectual equal. It is only through the teenager’s assertion that they are “in this together”, combined with him bringing his head back up to a neutral eye level, that both their relationship’s equilibrium and the dog’s humanity is once again restored.

This reconciliation is later reinforced in the second Scrabble scene, with Furface and Travis now using the game as a shared means of communicating their bond. While their initial interaction served as a means of questioning the dog’s parallel status, it is through their playing a round of Scrabble that the film firmly characterises Furface as a legitimate member of the Cornell family. As Furface and Travis play, they are seated symmetrically within the frame. In doing this, the film not only demonstrates their similarity to one another, but also the equality between Furface’s exterior and interior identities. Although the dog is once again using the tiles, this time he instead supplements his communication with barking, allowing his animality and humanity to be simultaneously displayed. This is coupled with the familial tone of the conversation, with the two bickering over the rules of Scrabble and who “beat” who as if they are siblings. Through these two hybridised and synergistic exchanges, Furface is therefore presented as not only an authentic addition to the family, but also as a true intellectual counterpart to humanity as a whole.

By representing Furface as an intellectual equal to the human characters, this enables the film to elevate humanity to a more virtuous and wholesome standing. Throughout the social evolution of the human-canine relationship, dogs were considered to inherently carry the best qualities of humanity within their nature, such as loyalty, courage, and compassion. Over time, the concept that these moral characteristics would translate across to humans through their canine associations would eventually, as Kennan Ferguson asserts, advance to the point where “loving a dog began to be seen as an intrinsic good”[2] by society.

Furface adheres to this idea of moral superiority, with him, despite his shared intellect, staying true to the ‘dog hero’ archetype whilst inspiring Travis to express similarly honourable traits. Through this, the film utilises their close bond, as well as their balanced interiorities, as a symbolic display of humanity’s overall goodness. This is particularly noticeable when, in an effort to flee from the OXCOM, the family escape through an upstairs window. Although Travis and Nora are aware that the OXCOM only “wants the dog”, they still adamantly preserve their new family unit by calling out for Furface as they race up the stairs. As Furface joins them, the camera switches from a high angle to a low one, concurrently conveying the danger that follows the characters whilst also emphasising the heroic dynamic that the dog’s presence provides. By willingly aligning themselves with Furface, Travis and Nora can therefore emulate his ‘canine attributes’ by associating them as part of both their equivalent intellects and familial responsibility to one another. In doing this, they are uplifted to a shared position of human goodness.

This leads to the later role reversal between Furface and Travis after they jump out the window. After remaining behind to distract the OXCOM long enough for Travis and Nora to escape onto the opposite roof, the dog is unable to make the leap towards them, with the camera tracking his slow motion descent as he falls to the ground. Travis, through both his newly elevated position above Furface and the transference of the camera’s low angles to him, is consequently encouraged to exhibit the dog’s honourable qualities by taking over as protector and firing at the OXCOM with his shotgun. These exchanged duties signify Furface’s role as a mentor-like figure, with his animal exterior and human interior’s unique perspective qualifying him as a genuine source of moral guidance to not only the teenager, but also the rest of humanity. Since Travis’s development and application of these virtuous characteristics enables him to become more like Furface, their intellectual equality with one another indicates an overall intrinsic betterment of human nature. This sentiment is reinforced when Travis rushes to help the injured dog. As he runs to the truck with Furface in his arms, the two are centralised in the frame, becoming a joint focal point in the shot. In doing this, the film merges them together, indicating their shared intellectual and moral standings. By being entwined with Furface, humans are therefore capable of growing into the same inherently virtuous beings as their canine companions.

By converting Furface from Man’s Best Friend to Man’s Intellectual Equal, the human perspective and ability to empathise is expanded far beyond the limited confines of cultivated civilisation. While the film directs the audience to recognise Furface primarily as an animal, the subtle camera techniques employed throughout challenges them to perceive his interiority in relation to their own. This allows him to simultaneously remain a dog, whilst also growing into something more.

Watchers utilises the relationship between Travis and Furface as an exploration of the lack of true understanding between humans and other species. It is only through the dog’s extraordinary nature, coupled with his addition to the Cornell family, that humans are once again granted the capacity to see the world outside of themselves. Furface therefore represents not only the animality humans have evolved from, but also what humanity can aspire to become.

Footnotes:

[1] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion, 2002), p. 41. ProQuest Ebook Central ebook.

[2] Kennan Ferguson, “I ♥ My Dog”, Political Theory, 32.3 (2004), 373-395 (pp. 377) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4148159>

Bibliography

Primary Source:

Hess, Jon, dir., Watchers (Universal Pictures, Alliance Releasing, 1988)

Secondary Sources:

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion, 2002) ProQuest Ebook Central ebook

Ferguson, Kennan, “I ♥ My Dog”, Political Theory, 32.3 (2004), 373-395 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4148159>

Image Bibliography:

Figure 1: thisisvhshell, Watchers (1998) – Trailer, Online Trailer, YouTube, 24 July 2013, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K8qNKxYG6mg> [accessed 3 January 2024]

Figure 2: Helcermanas-Benge, Chris, Watchers, Portrait Still of Corey Haim and Sandy the Dog, StudioCanal, 1988 <https://www.studiocanal.com/title/watchers-1988/> [Accessed 3 January 2024]

Figure 7: Dead Last Podcast, Watchers (1988) – Dog Uses Computer, Film Clip, YouTube, 31 July 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5cJQIUpt89I> [Accessed 3 January 2024]

Figure: 8: Devine, Alexis, Bunny the Dog Lounges with her Buttons, Photograph of Bunny the ‘Talking’ Dog, The Verge, 11 November 2020 <https://www.theverge.com/21557375/bunny-the-dog-talks-researchers-animal-cognition-language-tiktok> [Accessed 3 January 2024]

Figure 13: Rubens, Peter Paul, Saint Roch Fed by a Dog, c. 1623, Oil Painting, 68 x 97cm <https://research.rkd.nl/en/detail/https%3A%2F%2Fdata.rkd.nl%2Fimages%2F254398> [Accessed 3 January 2024]

Figure 14: Landseer, Edwin Henry, The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner, 1837, Oil Painting, 45.7 x 61cm <https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-old-shepherds-chief-mourner-30946> [Accessed 3 January 2024]

Further Reading:

Hanks, Robert, ‘Fall of the Wild: A Brief History of Dogs on Film’, British Film Institute, 2015 <https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/fall-wild-brief-history-dogs-film> [accessed 2 January 2024]

McLean, Adrienne L. and others, Cinematic Canines: Dogs and Their Work in the Fiction Film (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2014) ProQuest Ebook Central ebook

Seegert, Natasha, “Dogme Productions, with an Emphasis on the Dog: Revealing Animal Perspectives”, Film Criticism, 40.2 (2016), 1-15 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/48731242>