The Little Prince uses the animated medium of a children’s film to reconfigure the representation of the snake. A ‘common trope’ also applied here, is to present snakes as a certain bringer of death. The image of a reptile being posed as ‘cold-hearted aggressor’ is familiar as it goes back to Adam and Eve – the ‘icon’ of the snake is often framed this way, as to many they are exotic and unfamiliar.

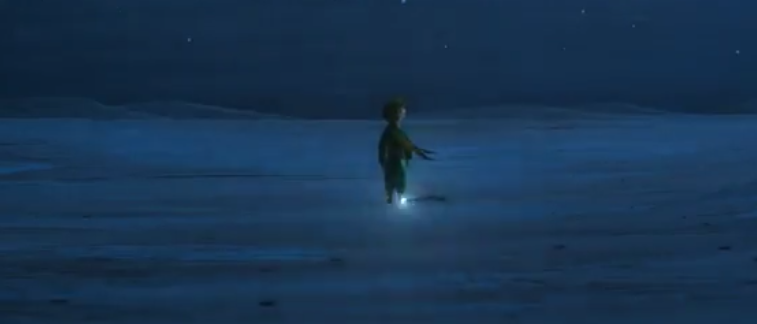

In the Prince’s final scene, the camera angle pans upwards from sandy naked footprints to a star-filled night sky. The Prince is walking away from the viewer, lit only by the moonlight. A small dark line approaches his ankle, moving swiftly through the sand. {Figure 1}The visual ‘suggestion’ of the snake works well to infer danger because of the shared cultural knowledge humans have of snake representation.The flicker of a snake on the path might bring to mind images of the ‘cold-hearted aggressor’ and of being bitten against one’s will. However, the unconventionality is created when there is no evidence of a violent ‘strike’ or recognisable fangs shown on screen.

The snake is portrayed as a single line in the sand, no prominent teeth or winding body to be seen. This works to disrupt our expectations of a traditional snake attack as the child has no graphic reaction to the snake’s presence, and there is no change in tempo of the music, or movement from camera angle to express the moment more objectively. This creates a strange moment for a children’s film, a death shown so closely and clearly but slowed in presentation to create a feeling of serenity and calm.

A twinkle of bells also occurs as the snake meets the ankle of the Prince- shown visually there is a sparkle glowing bright from the impact, that then fades. {Figure 2} The tranquil nature of the moment is reflected in the gentle sound of the bells. The extradiegetic sounds ensure that there is no jolting moment of change- instead a gentle transition. The bells create a further uniqueness as there is no vocal call from the Prince to those viewing, and no yells of pain. There is light violin music throughout the scene that does not vary or come to a crescendo – instead it keeps a steady and gentle pace. Like the music, the angle of the camera position allows the viewer to perceive the moment clearly. This moment re-imagines the classic snake bite scene in a way that is suited to the genre of children’s film- subverting the actual representation to create something that is palatable and emotional rather than an example of bodily horror.

The sublime setting of sand and stars shows the freedom of action from the snake, and how clear his intentions are. All of these elements create a peaceful moment within the film that is powerfully emotional due to the breaking of traditional expectations – the story is able to disrupt the discourse of snakes as unforgiving predators, and re-frame them as a friendly guide through the transition of life to death.

This re-framing is created when the snake and child first meet- The Prince has no fear of him as he has never seen a snake before, and the snake speaks, replying to the Prince coolly- stating ‘Good Evening.’ {Figure 3}The disruption of expectations is furthered when the snake approaches his ankle- as the ‘animal body is reduced to a plot device.’ Now, the icon of the snake is confirmed as a bringer of death- a terrifyingly instantaneous one. However, this ‘strike scene’ is represented in such a way it is not tense or alarming. There is absence of a fast paced predator/prey situation, instead the continuous shot allows us to perceive both the Little Prince and the snake as having agency.Classic snake ‘strike scenes’ paint a clear attacked/ attacker’s binary – which makes this moment feel so visceral. {Figure 4}The actual ‘animal body’ is in fact so far removed from the representation that our understanding of the scene is purely conjured through our cultural knowledge.

Bibliography:

[3] Ratelle, Amy. 2015. Animality and Children’s Literature and Film, Critical Approaches to Children’s Literature, 1st edition (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan)

[1] [2] Wells, Paul. 2009. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press)