“Everything about him is human, except that he cannot talk”

The Oscar winning documentary The Elephant Whisperers depicts the unique relationship between a Kattunayakan couple and an orphaned elephant in the Thepakadu Elephant Camp. After the mother of the young elephant is killed by an electric fence, Raghu is assigned to the care of Bellie and Bomman. Following the loss of Bellie’s daughter and Bomman experiencing a career-altering injury, the pair find an unlikely companion in Raghu, whilst simultaneously developing a bond between themselves that results in a marriage ceremony. In discussing wildlife films, Bousé suggests that “the orphan/absent mother device creates the conditions from which the rest of the story flows” (1) and indeed, the film’s narrative stems from the abandonment of Raghu and leads to a healing journey for the trio. Through this human-animal relationship, director Kartiki Gonsalves is able to present an empathetic view of elephants that highlights the need for conservation and protection of these animals and their environments. Over the course of this heart-warming film, we watch Bomman and Bellie care for Raghu like he is their own child and become parents for Ammu, another young elephant, until they lose him when he gets assigned to another handler. Despite the grief in the beginning, the overall tone is not one of suffering, instead Gonsalves is able to orchestrate a feeling of hopefulness as, in caring for these elephants, the couple have created a remarkable blended family.

Despite the breath-taking aerial shots and close-up animal shots, this documentary does not adhere to all typical conventions of an observational wildlife documentary. Instead, vèritè footage is interspersed with voiceovers and interviews from the couple themselves so a familiarity is detectable through the camera work, communicating the closeness of the handlers with Raghu. There is minimal inclusion of scientific facts or statistics which is complemented by the simple narrative, framed by voiceovers from Bomman and Bellie only. The director is able to take advantage of this simplicity to convey the sense that what is happening on screen is in the present and therefore using a version of the observational documentary to identify pressing issues of conservation that are communicated through the human-animal relationship on screen.

In an interview, Gonzales explicitly set outs her goals for making the documentary: “I wanted to be able to understand these beautiful beings on a deeper level and recognise their similar traits… I hoped to get people to want to protect them and their landscape”(2). This aim is beautifully reflected onto the parent-child relationship that emerges between the humans and animals. The film is littered with moments of child-like behaviour from Raghu that is encouraged, and often humorously reprimanded, in the way a parent would a human child. Raghu’s child-like nature is established as his tragic past is retold. Shaky footage depicts an emaciated Raghu lying on the floor followed by him tentatively reaching for the uniformed man’s hand with his trunk (Fig 2), which evokes the image of a child reaching for their parent for reassurance. This moment of connection simultaneously identifies Raghu’s vulnerability and likens him to a child, foreshadowing his presence in the Thepakadu Camp. This establishing sequence concludes with a static shot of Bellie and Bomman’s home, cementing them as safe and stable care for Raghu.

Moments later, Raghu is seen kicking a football around (Fig 3) and his fuller build is a stark contrast to his malnourished state. The mise en scène of this over-the-shoulder shot places Bellie in the foreground observing, Bomman in the background and Raghu, the only figure in complete focus, playing with the football. The centralisation of Raghu whilst Bomman and Bellie watch mirrors the image of human parents cautiously watching a child play. Here, a comical image is presented by playing with a football as the stereotypical roles that Bellie and Bomman fulfil, as a mother watching from afar whilst the father gets involved, foreshadows the successful blended family that develops over the course of the film. Gonsalves also centralises the elephant to subtly reinforce the motivation of the documentary which is to express the need to protect these animals.

To some degree Gonsalves anthropomorphises the elephants by equating them to the children of Bomman and Bellie, however in no way is this detrimental to the elephants, as doing so is often seen as an unnecessary blurring of species. In fact she makes an effort to show the vulnerability of the young elephants, exhibiting the solace they find in playfulness and their subsequent need for care from humans. As the reason they are orphaned is predominantly the fault of human activity, Gonsalves seems to suggests that its only fair that humans are the ones to help rehabilitate. Alternatively, if this portrayal is seen to be an anthropomorphism of Raghu and Ammu, then Gonsalves presents it in such a way that highlights the need to protect them. Another scene that observes how Bomman and Bellie care for Raghu is when they take turns to give Raghu food. The camera tracks Bomman entering a kitchen with people behind counters preparing food for the elephants. This is not only evocative of a school canteen serving food to its students, but also a subtle indication of the extent of this conservation project and again Gonsalves’ motivation can be seen to promote these places. The score is whimsical, reflecting the playful youth of the elephant which is enhanced by the pair approaching Raghu, teasing him by saying “look how naughty you are today” and touching him affectionately. But Raghu spurns some of the food they have prepared for him, prompting Bellie and Bomman to call him “naughty” again and chastise him for his picky eating habits. The act of feeding a young animal is an extremely maternal act, thus establishing the mother-son relationship embodied by the elephant.

For the first half of the film, breath-taking aerial shots portray the environment as something to be marvelled at, but the change of seasons is reflected in the tone of the film. Tensions rise as the score morphs into mournful strings accompanied by the isolated sound of fire crackling. Suddenly the possibility of another orphaned elephant becomes alarmingly real and, by employing the Kuleshov effect (3), feelings of apprehension come to a climax during a sequence of unnerving images.

The organisation of these shots prompt the audience to fear for the life of an elephant that a single shot of the change of seasons would not depict in the same way. It begins with a close up shot of the forest burning, identifying the danger as heat rises for the summer; an implication of the effects of the damages of climate change. Elephants are centralised by the following mid-shot of a herd, identifying them as the vulnerable animals and the fire crackling can still be heard, alluding to its proximity. Next a close-up shows a young elephant reaching for the leg of presumably its mother; this frame is similar to that of Raghu when he was rescued, thus aligning their vulnerability and mirroring Raghu in this elephant to heighten emotional investment. This vulnerability is exacerbated by the medium close-up of a vulture and finally a mid-shot of an elephant carcass. The slow zoom into this harrowing final image slows the pace of the sequence, giving time for the viewer to acknowledge the implication that this is the inevitable result of the preceding images. The sequence serves to highlight the vulnerability of the elephants, particularly the young, and therefore the way in which Raghu and Ammu benefit from the human-animal relationship presented.

To show the human benefit in this relationship, and why these animals are important, Gonsalves uses the blossoming relationship between Bomman and Bellie. Their partnership reflects what their relationship with Raghu has taught them and how he has brought them together. Their blossoming relationship culminates with their wedding, but again, the event is used to display a harmonious blended family involving the elephants, not exclusively the human relationship. Within the ceremony, they decorate the elephants, painting them in Ganesha’s image (Fig 11 & 12), as Bomman describes, which elevates them to a divine status. Whilst elephants are considered sacred in the Hindu faith, involving them in a wedding also speaks to the affinity that the couple have developed for the animals. Even following their marriage and the societal norms this breaks, with Bellie being a widow, Gonsalves does not engage with this narrative. Instead she focuses on the integration of elephants into their life and decides to foreground their need for protection. In caring for the elephants, Raghu teaches them to care for each other, adding to the mutual benefit of this human-animal relationship.

The confirmation of their unique family unit comes in a heart-warming scene involving Bellie’s granddaughter, Sanjana. At this point an even younger elephant, Ammu, has been placed in their care. Whilst Bellie tells Sanjana a traditional Kattunayakan story, the camera continuously cuts between static close-ups of Sanjana and Ammu, making them synonymous with each other and depicting the image of a family unit. The close-ups of Ammu diminish the presence of the metal bars of his enclosure into the edges of the frame so when a shot of the entire living space is shown, it should be a startling moment to see him behind bars. But instead of suggesting isolation, the warm lighting, comforting fire sounds and close-ups of his eyes, make him seem completely involved in these fire-side stories. The close-ups show him as distinctly animal, yet he does not appear out of place next to Bellie’s granddaughter, thus conveying his contentment in such close proximity with humans. The tale ends with “when you give them love, they give back in the same way” and this speaks to the confirmation of his position as a child, akin to Sanjana, within the family and the mutual affection they hold.

The notion of the bedside story is mirrored in the way that Bomman and Bellie demonstrate their love for Raghu. Quoting Gruen, Calarco asserts that “entangled empathy is an ethical ideal that combines both cognition and emotion to arrive at an understanding of the other’s situation and assist others with their problems” (4) and the empathy between human and animals is exactly that, an “ideal”. Whilst the elephant cannot fully understand the grief that Bellie is feeling, he plays a role in filling a void in her life. He benefits by receiving life-saving care after he being orphaned and Bellie benefits by having a child figure to direct her affection to. Water is a central image to the portrayal of the human-elephant relationship; the need for water unifies humans with animals in terms of a biological requirement, bridging the gap between species, whilst also presenting a harmonious image of familial intimacy. The film is structured by Raghu’s presence in the couple’s life: starting at his rescue, following his rehabilitation, his reassignment to another handler and finally Bomman’s frequent visits to see him. At every point in this structure, there is an image of either natural water or Raghu being washed by humans.

When it starts raining Bomman is shown to cover Raghu with his umbrella; this image encapsulate how Bomman feels about Raghu. The long shot is well-balance with the two focal points at the centre. There is almost an exact middle line between them, but Bomman disrupts this balance by reaching his umbrella to Raghu’s half of the frame. Of course a wild elephant does not need to be shielded from the rain but, in an act of protection that would conventionally be seen in the relationship of a father and son for example, the human-animal relationship on screen is exhibited. Therefore reflecting the selfless care that Bomman feels for the elephant.

The film concludes with Raghu being washed but this time by young boys. Gonsalves “chose to focus on the positivity of that co-existence, rather than the negative aspect of man-animal conflict” (5). The subgenre of conservation documentary is evident through the presentation of an apparent impartial perspective, but with positive co-existence, she subtly reinforces the need for conservation by altering our perception of the human relationship with nature. As the film closes on Bomman and Bellie playfully dressing Ammu, it seems irrelevant of the species, here we see a bond between parents and their surrogate child. The joyful exuberance of the children washing Raghu cements the need for continuous conservation and protection for these animals. By depicting children specifically, the scene is suggestive of the next generation also caring for the elephants, therefore providing a hopeful conclusion to the narrative.

Primary Resources:

The Elephant Whisperers. 2022. dir. by Kartiki Gonsalves (Shikhya Entertainment)

Secondary Resources:

(1) Bousé, Derek. 2000. Wildlife Films (University of Pennsylvania Press) <http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=3441988> [accessed 12 January 2024]

(2) Alpha Universe. 2023. ‘The Making of “the Elephant Whisperers” & the Power of Story to Change Minds’, Sony | Alpha Universe <https://alphauniverse.com/stories/the-making-of-the-elephant-whisperers–and-the-power-of-story-to-change-minds/> [accessed 12 January 2024]

(3) Mobbs, Dean , and Nikolaus Weiskopf. 2006. ‘The Kuleshov Effect: The Influence of Contextual Framing on Emotional Attributions’, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1.2: 95–106 <https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl014> [accessed 12 January 2024]

(4)Calarco, Matthew R. 2020. Animal Studies: The Key Concepts (Taylor and Francis Group) <http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=6310857> [accessed 10 January 2024]

(5) Thiagarajan, Kamala. 2023. ‘An Oscar for “the Elephant Whisperers” – a Love Story about People and Pachyderms’, NPR <https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/03/05/1160659634/the-elephant-whisperers-an-oscar-nominated-love-story-about-people-and-pachyderm> [accessed 12 January 2024]

Doniger, Wendy. 2019. ‘Ganesha | Hindu Deity’, Encyclopædia Britannica <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ganesha> [accessed 11 January 2024]

Sharma, Manik. 2023. ‘“A Beautiful, Natural Bond”: Oscar-Winning Director Kartiki Gonsalves on Her Elephant Short Film’, The Guardian, section Film <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/mar/13/elephant-whisperers-director-kartiki-gonsalves-interview> [accessed 11 January 2024]

The Elephant Whisperers. 2022. dir. by Kartiki Gonsalves (Shikhya Entertainment)

‘The Elephant Whisperers (Short 2022)’. 2022. IMDB <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt23628262/> [accessed 12 January 2024]

Figures:

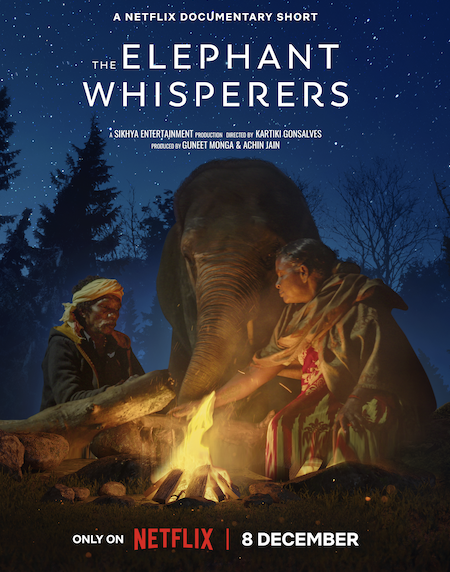

- Film Poster – ‘The Elephant Whisperers (Short 2022)’. 2022. IMDB <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt23628262/> [accessed 12 January 2024]

- Raghu being rescued – The Elephant Whisperers. 2022. dir. by Kartiki Gonsalves (Shikhya Entertainment)

- Raghu playing football – ibid

- Bellie feeding Raghu – ibid

- The forest burning – ibid

- An elephant herd – ibid

- A young elephant beside an older elephant – ibid

- An abandoned elephant – ibid

- A bird of prey – ibid

- An elephant carcass – ibid

- Image of a statue of Ganesha – Doniger, Wendy. 2019. ‘Ganesha | Hindu Deity’, Encyclopædia Britannica <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ganesha> [accessed 11 January 2024]

- The elephants decorated for a marriage ceremony – The Elephant Whisperers. 2022. dir. by Kartiki Gonsalves

- Bellie tells a fireside story – Youtube link

- Bomman washes Raghu – The Elephant Whisperers. 2022. dir. by Kartiki Gonsalves

- Bomman washes Raghu – ibid

- Young boys wash Raghu – ibid

- Bomman shields Raghu from the rain – ibid

- A child washes Raghu – ibid

Further Reading:

Bousé, Derek . 2009. ‘Are Wildlife Films Really “Nature Documentaries”?’, Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 15.2: 116–40 <https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039809367038> [accessed 14 January 2024]

Pandaya, Sonal . 2023. ‘Kartiki Gonsalves on the Elephant Whisperers: “Bonds I Will Have for Life”’, Hindustan Times <https://www.hindustantimes.com/entertainment/others/interview-kartiki-gonsalves-on-the-elephant-whisperers-oscars-nom-and-more-101675162431777.html> [accessed 15 January 2024]

Prince, Stephen , and Wayne E. Hensley. 1992. ‘The Kuleshov Effect: Recreating the Classic Experiment’, Cinema Journal, 31.2: 59–75 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1225144> [accessed 9 January 2024]

Rajan, Babu. 2023. ‘Poetics of Fostering the Animal: The Elephant Whisperers’, India Art Review <https://indiaartreview.com/stories/the-elephant-whisperers-oscar-human-animal-co-existence/> [accessed 12 January 2024]

Siddiqui, Aisha. 2023. ‘Elephants in Films: A Cinematic Journey through Conservation’, Wildlife SOS <https://wildlifesos.org/elephant/elephants-in-films-a-cinematic-journey-through-conservation/> [accessed 11 January 2024]

Further Viewing:

Love and Bananas. 2018. dir. by Ashley Bell (Abramorama)

The Elephant Queen. 2018. dir. by Victoria Stone and Mark Deeble (A24)

The Urban Elephant. 2011. dir. by Allison Argo (National Geographic)