Evolutionary Reversal in Planet of the Apes

Planet of the Apes (1968) brilliantly satirizes the process by which humans simultaneously invented the concept of the “animal kingdom” and appointed themselves to its highest position. Adapting Pierre Boulle’s celebrated novel, Monkey Planet (1963), director Franklin J. Schaffner and screenwriters Rod Serling and Michael Wilson use the speculative licence of the science fiction film genre to create a unique heightened “reality” where an alternate form of evolution has favoured apes over humans as the dominant species on Earth. The traditionally recognized qualities of each species have been reversed. This subversion of the natural order gives rise to the subversion of the human social order, as the inherent arbitrariness of human characteristics and values are revealed when projected onto simian entities; the film makes the viewer aware that evolution could just as easily have gone the other way. The desired effect is to humble all human thought, including the idea that humans are at the top of the natural order.

As Richard von Busack notes in his article “Signifying Monkeys: Politics and Story-Telling in the Planet of the Apes Series,” the source novel metaphorically substitutes apes for non-white races. It is well-documented that “[the author] had been a colonialist and an engineer on a Malaysian rubber plantation. He was there when the Japanese invaded in 1941, an experience he parlayed into his celebrated novel, The Bridge on the River Kwai. It’s no secret that many Western colonialists considered the Asians as subhuman” (Busack, 168). Screenwriters Serling and Wilson turned Boulle’s racist colonial allegory into a liberal satire of speciesism concerning astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston) and his time traveling adventure to a planet with a reversed evolutionary ladder.

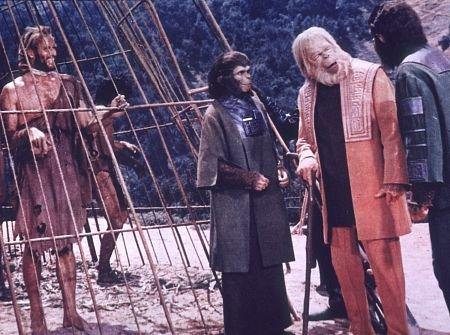

Upon landing his spaceship on what he perceives to be a different planet from the distant future, Taylor is trapped by a battalion of gorillas and taken to a facility where he can be examined by two benevolent chimp scientists, Dr. Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) and Dr. Zira (Kim Hunter). Once it is discovered that Taylor can speak – unlike the other speechless humans on the planet – the fearful gorillas want to kill him in order to prevent any possibility of reproduction. Dr. Cornelius and Dr. Zira, on the other hand, are sympathetic to Taylor’s situation as an anomaly and want to continue their examination of him. Enter Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans), the orangutan bridge between the angry hawkish gorillas and the liberal chimps. Dr. Zaius sympathizes with both the gorilla’s desire to prevent an evolution in intelligent humans by killing Taylor and with the peaceful, science-minded chimps. In the end, Dr. Zaius and the gorillas’ fear of humans is justified by the last standing monument to the warlike age of humanity: the iconic ruined Statue of Liberty, as seen in the film’s unforgettable last shot. The Planet of the Apes is revealed to be a human-destroyed Earth.

Planet of the Apes follows a 1950s science fiction film trend in that it is “often a political allegory, reflecting the Cold War debate in America between the military hard-liners and advocates of containment of the Soviet Union” (Busack 169). However, it subverts the usual outcome of this approach to filmmaking, for the non-human monster variables – which were often symbolic of the Communist menace and came in the form of everything from giant insects to alien vegetables – ultimately turn out to be humans. The apes, with the exception of the liberal chimps, are the monsters in the film until the twist ending, when it is revealed that human hostility – backed by a scientific nuclear arms program that had been spawned from social tensions that included religion – resulted in the reversal of the evolutionary order.

The film exposes the vulgarity of human values through evolutionary reversal in the following ways: the apes keep humans locked up in zoos and museums, highlighting the cruel human treatment of animals outside the world of the film; the apes believe in a religion that prevents them from considering that another species has the potential to be their intellectual equal, deflating the arrogance cultivated by off-screen humans; and the surprise ending argues that humans are the root of all evil in the world, for they caused a nuclear holocaust that wiped out the majority of their own kind, paving the way for the apes to evolve into “superior” beings.

Above: Astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston) is observed by Dr. Zira (Kim Hunter), Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans), and Dr. Cornelius (Roddy McDowall). Planet of the Apes. Dir. Franklin J. Schaffner. Twentieth Century Fox. 1968.

In order to create a cinematic world in which these speculative ideas on evolution can be believably presented to the audience, Franklin J. Schaffner employs the talents of composer Jerry Goldsmith and cinematographer Leon Shamroy. Goldsmith samples from the dissonant sounds in the music of Igor Stravinsky to create a foreboding, otherworldly score. He also particularizes the tension of this ape planet by adding electronic simian noises to the soundtrack. Complementing the music are Shamroy’s distorted, expressionistic camera angles that visually accentuate the warped hierarchy of the ape planet. With the establishment of this heightened “reality,” the filmmakers are able to explore the thematic content in a satiric but believable fashion.

Exhibiting live humans in zoos and dead ones in museums, the apes give humanity a taste of its own medicine. By showing the humiliation that these on-screen humans have to endure, off-screen human viewers are supposed to feel guilty about how they treat apes and other “lesser” animals. This violation of the natural order dismantles the social order, both of which are dictated by humans. It is also a microcosmic example of the film’s subversion of the “continuum of integrity, or respect, that audiences and cultural creators accord to animals in visual culture” (Malamud 4). The humans are not eager participants in the apes’ entertainment spectacles; the apes abuse them in a variety of sadistic ways that exist at the bottom end of the aforementioned continuum: “There are dancing bears, piano-playing chickens, rabbits being pulled out of hats, chimps in human clothing on parade, ‘stupid pet tricks,’ elephants with paintbrushes taped to their trunks in ecotourist camps, and so forth. That is: animals doing silly things for the audience’s amusement—things they don’t usually do, and have no reason to do” (Malamud 4).

Serling and Wilson are essentially pleading with the audience to apply the Golden Rule to animals outside their species. This conservationist mandate is born from the film’s larger subversive mandate, which is to expose the arbitrary nature of human supremacy through the reversal of the evolutionary process. Humans are prone to engage with other animals “in ways that hurt their spirits and impinge upon their welfare. The consequence of most human-animal encounters is the expression of harm via pathways of power” (Malamud 2). Humans are not the ultimate power in the world; they are capable of helping themselves navigate through existence, but they are incapable of understanding the most fundamental inner-workings of any part of it. In the film, the apes mistreat the humans. The apes look like apes but behave and dress like humans. The adaptation of the façade of human superiority gives the apes the moral “right” to abuse the humans. Of course, the very act of dramatizing this behaviour reveals its inherent ugliness.

Above: Astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston) encounters a stuffed human in the apes’ museum.

Planet of the Apes. Dir. Franklin J. Schaffner. Twentieth Century Fox. 1968

By humanizing the apes and dehumanizing the humans, the apes are mainly portrayed in a pejorative manner. The evolutionary reversal that attributes human values to apes forces the human audience to see the errors of their species’ ways (if they have not done so already). Planet of the Apes’ ultimate subversive coup is that it reveals human supremacy to be an idea rather than a “reality.” This allows human viewers to see themselves and their place in the world through a new humbling lens. It can also help them navigate through similar human-animal reversal films. The Creature from the Black Lagoon series, for example, tells the story of a human-fish hybrid that is captured in the Amazon River, brought back to the United States, displayed in an amusement park, and eventually operated on to become fully human. Unfortunately, the operation leaves the creature literally and figuratively unable to live on either the land or the sea.

The tragedy of the Gill-Man is that humans are the more inhuman species. But Planet of the Apes pushes the moral further by arguing that all human powers of consciousness are the result of an arbitrary evolutionary process, reminding viewers to be less precious about their thoughts. Humans may have evolved to the point where they believe to be superior to other animals, but they are not evolved enough to understand themselves or anything else at the most fundamental level. Nevertheless, curiosity is an insatiable parasite of the human mind. The power of the human imagination not only allowed the film’s fictional apes to become ciphers for humanity, but determined the need for the evolutionary reversal lesson to be taught in the first place.

Further Reading:

Boulle, Pierre. Planet of the Apes. 1963. New York: Del Ray, 2001. Print.

Greene, Eric. Planet of the Apes as American Myth. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University of New England Press, 2000. Print.

Hofstede, David. Planet of the Apes: An Unofficial Companion. Toronto: ECW Press, 2001. Print.

Bibliography:

Buckle, Andy. “Scene Analysis: Planet of the Apes (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1968).” 2011. JPEG.

Busack, Richard von. “Signifying Monkeys: Politics and Story-Telling in the Planet of the Apes Series.” The Science Fiction Film Reader. Ed. Gregg Rickman. New York: Limelight Editions, 2004. 165 – 178. Print.

Gorbie. “PLANET OF THE APES (1968) Soundtrack Score Suite (Jerry Goldsmith).” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, May 26, 2012. Web. April 5, 2014.

Malamud, Randy. “Animals on Film: The Ethics of the Human Gaze.” Spring, Vol. 83, Minding the Animal Psyche (2010): 1 – 26. Print.

Planet of the Apes. Dir. Franklin J. Schaffner. Twentieth Century Fox. 1968. Film.

Vintage Film Trailers. “Planet of the apes 1 (1968) – Trailer.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, May 8, 2010. Web. April 5, 2014.

Winward, Andy. “Planet of the Apes.” August 20, 2011. JPEG.

Keywords: apes; gorillas; chimpanzees; monkeys; orangutans; humans; science fiction; satire; subversion; speciesism; evolution; evolutionary reversal; film adaptations.