Hayao Miyazaki’s 1984 film ‘Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’ follows the adventures of a young princess named Nausicaä who is part of one of the last tribes of humans remaining on Earth. A toxic forest has taken over most of the world as a result of mankind’s pollution; Nausicaä seeks to save the world by studying the forest and the creatures within it, despite the fact that they could kill her at any moment. Nausicaä has a special connection with the forest, particularly with the gigantic insects prone to bouts of blind rage known as the Ohmu, and she is forced to leave her village in order to save both humanity and the Ohmu from the threat of war from neighbouring Tolmekians and Pejites. In the end, Nausicaä sacrifices herself to the Ohmu to prevent further bloodshed and show the humans that they need to work with the forest and not follow the path of destruction set out by the Tolmekian warrior princess Kushana.

As one of the first feature films directed by Miyazaki this production was a key addition to the animé genre ‘Nausicaä was so important in the creation of Studio Ghibli that it is often mistakenly thought of as a Ghibli film, and has subsequently been released under that very label.’ [1] Studio Ghibli films are so stylistically unique that they could even be considered to be their own sub-genre and Nausicaä is where a great number of the recurring Studio Ghibli tropes began. The binary oppositions of humans versus the environment and technology versus nature are very prevalent in Nausicaä and continue to be found in almost every other Studio Ghibli film from the wolves versus the iron workers in Princess Mononoke to broomstick versus airplane in Kiki’s Delivery Service. However, Nausicaä is also a typical adventure film in many ways, for example the narrative follows Todorov’s ‘“punishment evaded”’ [2] theory of narrative structure of ‘equilibrium-disequilibrium-equilibrium’ [3] broken up into smaller sub-plots. Another trope of the adventure genre is the coming of age of the protagonist, through her journey to adulthood Nausicaä is given no choice except growing up for her to be able to deal with serious issues like death, war and greed. However, for the film to retain accessibility for children and its PG rating, these mature topics are combined with the animé genre in order to create the ‘suspension of disbelief’ [4] which allows the text to avoid scaring or boring younger audiences.

Although there are many instances where animals are prevalent in this film, the most significant all involve the Ohmu specifically. The Ohmu are important symbolically in many ways; their name alone is loaded with meaning through its link with the Ohm in physics which is a ‘unit of electrical resistance’[5] as well as its link with Om in Hinduism, which represents ‘all that exists’[6]. The film begins and ends with scenes featuring the Ohmu, symbolising the cycle of nature from birth to death whilst also embodying the opposition between nature and humanity through their emotional extremes of love and hatred. These extremes are evidenced through their connection to technology with Ohms combined with their connection to the universe in Om, suggesting that the Ohmu are a symbol of the unison of humanity and nature. The connection with Om is also significant because of a scene where Nausicaä finds an Ohmu shell and hits it with her sword to make a clear, ringing sound. When this is connected with the fact that she later calms down an Ohmu from a blind rage with an ‘insect charm’ which emits a similar clear, soothing sound, it shows the Ohmu as a representation of the pure and innocent through their connection with sound.

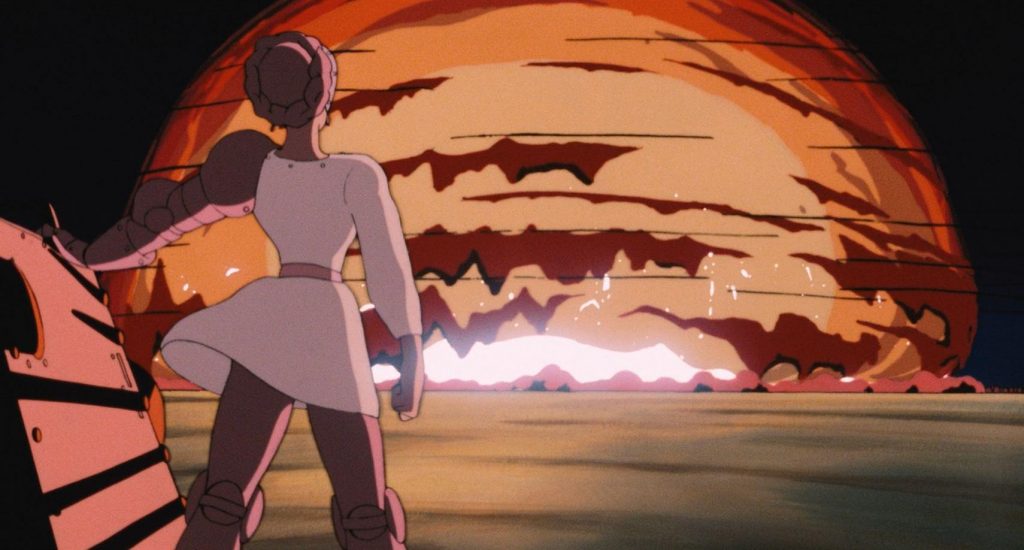

However, only Nausicaä sees this in the Ohmu and the warrior princess Kushana tries to use an ancient monster to destroy the creatures ‘For her, the ends, however terrible, justify the means.’[7] This is a reference to the use of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima as when it is used against the Ohmu a mushroom cloud is formed and Obaba a kind of seer says ‘If humans have to rely on a monster like that then we don’t deserve to survive’ [8]. The use of the monster links back to the human versus environment theme, when one insect is killed it enrages all of them, the insects are trying to protect against the humans who have not learned their lesson which is obvious through the use of the monster against the Ohmu. The use of animé to explore these issues is very important, although overall the humans are depicted as ignorant they are also represented as morally ambiguous because each tribe is trying to save humanity but with different methods. Nausicaä is a film which uses animation to work through the death of a parent, war, ignorance and moral ambiguity to teach younger viewers that not every issue is as black and white as it may seem. This text is ‘an animated fairytale that can play with generic orthodoxies and real world expectations.’ [9] This is because animation provides a disconnect between the viewer and the subject, for example films such as The Pianist which examine WW2 are very distressing because of their direct engagement with the horrors of warfare. However Nausicaä enables the viewer to engage with the theme of war without such distress because ultimately, it is not real for the audience.

The narrative structure of this film is also central to the representation of the Ohmu. Todorov theorised that most narratives follow a similar structure, this begins with the ‘equilibrium’ [10]. At the start of Nausicaä there is equilibrium in the village as a new baby has been born and everything is content, then a Tolmekian airship crashes in the valley causing the start of the ‘disequilibrium’[11] and the film ends with everyone being saved by Nausicaä, thus returning the narrative to Todorov’s final ‘equilibrium’ [12] stage. The Ohmu are an important narrative tool which drive the narrative forward, beginning with their spiritual connection with Nausicaä when her plane crashes in the toxic forest and ending with their influence on the final disequilibrium. The Ohmu are most important symbolically, Nausicaä has a spiritual connection with the creatures which is prevalent in her childhood memory scenes, and this innocent link is shown at the end of the film as the saviour of humanity. Nausicaä tried to save a baby Ohmu in her childhood which is why the Ohmu return the favour at the end when they save her. The Ohmu can be incandescent with rage but they can be equally innocent and pure, these oppositional themes are another representation of the binary oppositions such as humans versus nature found throughout this film.

Generally animals are represented as wild, dangerous and instinctive in this film, all of the humans except Nausicaä hate the insects and want to burn the forest down. The Tolmekians want to use the animé equivalent of an atomic bomb to wipe out the forest because of their blind hatred and the villagers in the valley don’t want to go as far as the Tolmekians but are still afraid of the insects. However, Nausicaä sees the beauty in the toxic forest and seeks to live in harmony with it, she even brings some of the plants into her castle to better comprehend the forest’s ways, but she knows that the villager’s fear would prevent them from understanding her studies. Through the Ohmu protecting their habitat the Tolmekians are shown to be full of hatred, the villagers are revealed as fearful and the Pejites are exposed as ignorant. These three groups show how most people relate to something they don’t understand, and the animals in this film are an analogy for the misunderstood ‘other’. The Ohmu are a representation of animals which allows us to better understand ourselves and therefore the reasons why we used the atomic bomb; but the Ohmu also show us why it shouldn’t be used again. The animals in this film are also represented as an ecological warning to humanity, they represent nature and are inherently morally good because they are preventing the total destruction of the planet. The animals are also presented as having a higher purpose than merely existing, and they have a conscious mind that is on a par with humans. They can actually communicate more effectively than humans, if one insect is killed it enrages the entire forest, but when the humans try to communicate between airships they have to flash lights at each other in Morse code. However, the insects think with a collective conscience and behave in a way that is for the collective good of the planet.

In comparison, Life of Pi presents animals as only having base instincts and as being incapable of any higher feeling or bond. Near the beginning of the film Pi’s father tells him that the tiger can never be his friend and demonstrates this by making him watch the tiger kill a goat. Conversely, Nausicaä has a deep bond with the Ohmu that ultimately saves her life, whereas in Life of Pi trying to take care of the tiger nearly kills him. These two films provide contrasting points at opposing ends of the anthropomorphism spectrum, like many animated films Nausicaä presents animals as being more deeply aware of the environment than humans whilst Life of Pi is at the opposite end; after spending time with a tiger only to come to the conclusion that it has no higher intelligence. Many other Studio Ghibli films also fall at the Nausicaä end of the spectrum, such as Princess Mononoke which shows humans as ignorant of nature’s forces.

[1] Michelle Le Blanc and Colin Odell, Studio Ghibli: The films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, (Harpenden, Herts: Kamera2009), p. 46.

[2] Dorothy J. Hale, The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory 1900-2000, (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford: 2006), p. 191.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Paul Wells, ‘The Animated Bestiary, Animals, Cartoons, and Culture’, (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, February 2009) p. 49

[5] “ohm”. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. 25 Nov. 2015. <Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/ohm>.

[6] Subhamoy Das, “Om or Aum: Hindu Symbol of the Absolute”, Hinduism.about.com, 25 Nov. 2015. http://hinduism.about.com/od/omaum/a/meaningofom.htm

[7] Michelle Le Blanc and Colin Odell, Studio Ghibli: The films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, (Harpenden, Herts: Kamera2009), p. 47.

[8] Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Dir. Hayao Miyazaki. Studio Ghibli. 1984

[9] Paul Wells, ‘The Animated Bestiary, Animals, Cartoons, and Culture’, (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, February 2009) p. 49

[10] Dorothy J. Hale, The Novel: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory 1900-2000, (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford: 2006), p. 191.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.