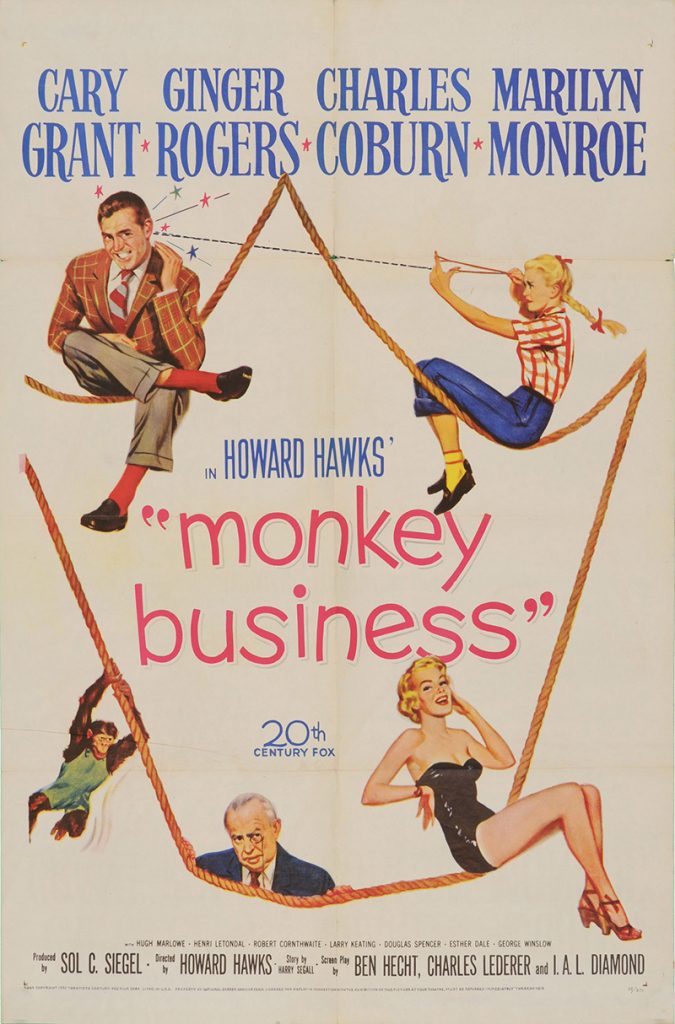

Forever young – what seems to be an unrealistic and silly fantasy to some, is Dr. Barnaby Fulton’s (Cary Grant) everyday life: in Howard Hawk’s screwball comedy Monkey Business (1952), he tries to develop a formula which reverses the ageing process. Even though Barnaby is completely dedicated to his work, he fails. It isn’t until one of the chimpanzees in the laboratory, Esther, mixes her own intensified version and pours it into the water dispenser that the formula finally has a significant rejuvenating effect on whoever drinks it. Not only is contaminated water drunk by Barnaby, but also by his wife and later on his boss and his colleagues. Watching the characters being under the influence of the formula and facing consequential problems between marriage, sexual desire and work turns Hawk’s film into a “druggie-surrealist masterpiece” (Bradshaw 2011).

Monkey Business is one of the older attempts at screwball comedy and often written off as a copy of Howard Hawk’s highly successful film Bringing Up Baby (1938). Not only do both Hawk’s comedies share a genre and lead actor, but both films feature furry cast members: in Bringing Up Baby, Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn tumultuously share joint custody of a somewhat domesticated leopard, whereas 12 years later, Grant’s colleagues are two – uncredited – chimpanzees.

Much like in Bringing Up Baby, Grant plays a scientist, who seems to be spending more time with his work than with his wife (Ginger Rogers). This character trait is actually typical for the genre of the screwball genre: at the centre of these comedies is a couple, whereas the often frustrated male protagonist is usually depicted as someone who loses touch with his private life. This basis functions as a playing board for a genre that focuses “on romantic couples and their conversation about love and sex” (Halbout 2014: 61) by using tools such as “puns, visual metaphors, symbolic objects, recurring editing techniques and use of gags” (ibid.: 68). Just like in other screwball comedies, Edwina and Barnaby are faced with the issue of unifying sexual desire and marriage in order to find their happy ending.

Screwball comedies present somewhat modern gender roles: in the battle of the sexes, that is between the two partners at centre, the female protagonists are usually depicted as confident, energetic, headstrong and sometimes eccentric characters. It is upon the ladies of the genre to actively forward the story by trying to achieve their personal goals. One of these goals is to turn the couple’s normal romantic relationship into a sexual one.

This applies to Edwina Fulton, Barnaby’s wife. However, there are two sides to Edwina: on the one hand, she is depicted as a stereotypical housewife who seems to enjoy nothing more than cooking for her husband. On the other hand, she is constantly reminiscing about their honeymoon and therefore presenting herself as a somewhat sexual being. However, this representation of women was not welcome by the American society of the 1950s and therefore needed to be cleverly concealed. Therefore, the screwball comedy mastered the art of innuendo, and the narrative techniques in Monkey Business are a perfect example for this “double entendre” (Halbout 2014: 66). Here, not answering the telephone e.g. becomes a metaphor for having sex. In one scene (6:24-6:40), Edwina, Barnaby and one of their friends are in their kitchen and the couple is flirting while ignoring the ringing phone. Here, the couple’s friend actually helps the audience to understand the subtext by saying “The language is confusing, but the actions are unmistakable” (Hawks 1952, mins. 11:13-11:17). In another scene, Barnaby and Lois, the laboratory boss’ charming, yet ditzy secretary, played by Marilyn Monroe, are about to take Barnaby’s new flashy car for a spin. While getting in the car, she asks him if the motor is running, whereupon he asks Lois if her motor is running. He then tells her that “it takes a while to warm up” to which she cheekily replies “does me too” (ibid., mins. 32:08-32:20).

However, it isn’t actually Edwina, who solves the problem and establishes sexual contentment in the marriage. It isn’t even Loise. The female character who is actually responsible for the couple’s happy ending is an entirely different woman: it is Esther, the chimpanzee.

Oppositions are the heart of every screwball comedy: not only the battle of the sexes, that is male versus female. Esther’s first scene (Hawks 1952, mins. 15:27-18:42), in which she has escaped her cage and the scientists try to capture her, also depicts other kinds of oppositions: natural behaviour versus artificial behaviour and wild versus order. When the chimpanzee, a subject of animal testing, is first introduced, the scientists think that she is under the influence of the formula and therefore acting very lively and wildly. The scientists, including Barnaby, keep saying how “strange” the animal’s behaviour is, that is they cannot imagine the formula having this kind of effect on her. However, since Esther has not actually taken any of the formula, she is acting uninfluenced and therefore instinctively and natural. Nothing should be strange about an animal acting naturally, that is being lively and moving around. Based on the humans’ reaction to the animal’s natural behaviour, one could ask how chimpanzees normally act in the laboratory: are they being tranquillised in order to be easier to handle and work with? Barnaby even asks his colleagues if they have given the monkey stimulants, which supports this suggestion.

Another opposition introduced by this scene and subsequently depicted in the film is the one of human versus animal: this theme is especially visible in the relationship of Barnaby and the chimpanzees. But these two opposites do not only confront each other, but actually merge by anthropomorphising the monkey. The humanisation of the animal is particularly realised in the following two scenes, which function as mirror scenes. The first one shows Barnaby working on the formula and experimenting. The second one shows Esther doing the same thing. As for the mirroring, there are certain differences in the way both individuals perform the experiments. Barnaby works highly professional: he changes into a white coat, he names the ingredients in Latin, he double-checks their specific measurements, which he has neatly listed, and uses tools in order to do so. In contrast, Esther doesn’t measure any of the ingredients, she makes mistakes and most significantly, she licks the lids and finally drinks the formula herself before pouring it into the water supply. Even though this scene humanises her, this depiction is quickly dissolved by the janitor: he puts Esther back in her cage while saying “whichever one you are”. He doesn’t only deprive her of her identity, but reminds the audience that even though she just performed a highly intelligent task, she is still just an animal (Hawks 1952, mins. 18:43-24:15). Also, by drinking the formula herself, Esther breaks the rules, which have been established and explained by the film before (“Self-experimentation is against the rule of all research”). Again, this represents her as wild and unruly and also further differentiates her from Barnaby, that is from humans.

Ultimately, it is Esther’s wild nature that helps the couple to achieve their happy ending. She is the catalyst, and kind of passes her wildness on to the humans. By experimenting in a disorderly fashion, the chimpanzee’s formula is actually successful and by consuming it, the married couple rediscovers their young and wild side, that is their sexual desire. Therefore, they move away from the boring bourgeois life (which is frowned upon by screwball comedies), and after a loud, chaotic and silly adventure sparked by a monkey, the battle of the sexes ends in unity.

Esther seems to be one of the leading ladies in the film. However, her representation is definite: Esther isn’t a pet, she isn’t a companion, she is a test subject in a laboratory, where she is used to the humans’ benefit. At the same time, the chimpanzee are highly humanised, which presents them in a very positive way: first, the monkeys are dressed in peoples’ clothes. Due to a conversation Barnaby has with the janitor, which almost seems like an interaction between a father and the nanny of his children, the viewer also learns that they are having baths regularly. Second, Barnaby talks to Esther as if she were a human: when trying to recapture her after she escaped her cage, he reasons with her in a human way and calms her down with words, rather than just trying to physically capture her. Also, while working on the formula, the scientist isn’t only being watched by the chimpanzee from her cage, but he also interacts with her, e.g. by asking her questions about the way he is working, which she then actually answers by shaking her head (ibid., mins. 18:59-20:46). Like before, it seems as if they are able to comprehend each other and communicate successfully. In addition, whenever Edwina and Barnaby consume the formula, their behaviour is presented similar to Esther, that is unruly, loud and wild, and therefore the boundaries between human and animal blur. It is only due to this stark humanisation that Esther is able to take the place of a female character that forwards the plot of the film.

At the heart of every screwball comedy is a couple: a man and a woman, whose different character traits start a battle of the sexes, when all that they want is a healthy, successful romantic relationship encompassing sexual contentment. Director Howard Hawk mastered Hollywood’s tools to cleverly conceal this plot and he has also learned that an animal is a perfect catalyst, but also concealer for the typical screwball comedy plot: in Bringing Up Baby, Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn had to take care of a leopard. In Monkey Business, it is a chimpanzee that supports the couple in achieving their goal, whereas it doesn’t get much care. Being an animal testing subject and not leaving this position, Esther seems to be a means to an end. Nowadays, a film like Monkey Business might not be as successful, because there seems to be more awareness about animal testing and the viewer would not be content with the fact that there is no happy ending for Esther, who remains in the laboratory. Often, films that do address the issue of animal testing follow a plot in which the animals are freed or escape, e.g. in Rise of the Plant of the Apes or The Plague Dogs. Still, Monkey Business is a funny, fast-paced, loud comedy and “an amazing kind of Darwinian level playing field between apes and humans” (Bradshaw 2011).

List of Works Cited

Bradshaw, Peter. “Monkey Business – it’s an Ace Ape Jape”

The Guardian. 17 Feb 2011. Web. 23 Jan. 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2011/feb/17/howard-hawks-monkey-business.

Halbout, Grégoire. “The Impossible Sex Life of Couples in the Screwball Comedy.” Intimacy in Cinema: Critical Essays on English Language Films. David Roche and Isabelle Schmitt-Pitiot,

Jefferson: Mac Farland, 2014. 61-72. Print.

Hawks, Howard, dir. Monkey Business. 20th Century Fox, 1952. DVD.

Wulff, Hans J. “Screwball Comedies: Ein enzyklopädischer Artikel”

Medienwissenschaft Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 003.2003. 44. Web. 25 Jan. 2016. http://publikationen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/frontdoor/index/index/docId/13701.

List of Films mentioned

Hawks, Howard, dir. Bringing Up Baby. RKO Radio Pictures, 1938. Film.

Rosen, Martin, dir. The Plague Dogs. United Artists, 1982. Film.

Wyatt, Rupert, dir. Rise of the Planet of the Apes. 20th Century Fox, 2011. Film.

Further Reading

The Monkey Business IMDb Page: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0044916/?ref_=nv_sr_4

A New York Times film review of the film from its release year: http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9A0DE5DC133AE23BBC4E53DFBF668389649EDE

Monkey Business on Rotten Tomatoes: http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1014138-monkey_business/