Welcome to Jurassic World – the planet’s most amazing theme park! Take a vehicle tour through Gallimimus Valley and run with the fabulous flocks, or roll around in the gyroscope to get up close to your favourite docile dinos. If you’re looking for a fright, check out the wow-tastic Mosasaurus feeding shows! And new for 2015, introducing the truly terrifying Indominus Rex ™, the park’s first hybrid creation.

It appears that no lessons were learnt from the first Jurassic Park (1993) film. Set 22 years later, we see the theme park open in Jurassic World. When the Indominus escapes its enclosure, it leaves a murderous trail of destruction throughout the park. Through the chaos, the film follows Zach and Gray Mitchell, two brothers who visit the park while their parents deal with divorce, their aunt Claire Dearing, the park operations manager, and hunky raptor trainer Owen Grady, who becomes her love interest.

Just as guests flock to the over commercialised space of the park, guests in 2015 flocked to the cinema to see the latest CGI blockbuster. In both the world of the park and the world of cinema, it is the advancements in technology which bring in the big bucks, and the dinosaurs on screen certainly look the real deal. Despite being a science fiction thriller/ disaster movie, Jurassic World could be seen as a feel-good family film or rom-com, something achieved through Zack and Grey’s brotherly bonding, and the flirty quips made between Claire and Owen as each try to prove their authority. At times, the film seems satirically light hearted considering the amount of bloodshed it depicts, allowing viewers to experience a voyeuristic pleasure in watching people being eaten alive, without feeling guilty or horrified. Amongst the action, the film does however pose ethical questions about animals and science. The malevolent nature of the Indominus is an embodiment of science going too far, the hybrid dinosaur being much more intelligent than originally thought, something which simultaneously criticises the viewing of animals as ‘assets’ rather than emotional and dangerous living beings. [1] The film additionally promotes a compassion and understanding of animals, primarily though Owen’s relationship to ‘his’ raptors, whilst condemning security operator Vic Hoskins, who wants to use the dinosaurs as military weapons. [2]

It is clear from the opening of the film that the dinosaurs in Jurassic World are given a less-than-animal status. When showing potential investors around the science labs Claire describes the creation of dinosaurs through business-like jargon such as ‘asset development’, a phrase which deliberately avoids reference to creation of dinosaurs as living things. [3] Dressed in white with pristine helmet-like hair, Claire’s appearance at the start of the film is suggestive of the cold, clinical approach to the science she is trying to sell. She is, as Richard Dyer states ‘on automatic pilot’, the managers are like ‘perfectly turned-out Stepford people’, simply going through pre-rehearsed procedures. [4] Likewise, when taking to the park’s CEO early in the film, Claire states that ‘guest satisfaction is steady, in the low 90s. We don’t have a way to measure the animal’s emotional experience’, appearing confused as to why the animal’s emotions would be a concern. [5] At this point in the film, Claire’s only interest is profit, even leaving her nephews with her hapless assistant to attend important meetings – her job is about pleasing customers and investors (a trivial concern to the multimillionaire CEO who values experiences over profits), keeping her disconnected from the animalistic nature of the dinosaurs. As Owen tells her, it is easier for Claire to think of these animals as ‘numbers on a speadsheet’, emotionless objects of spectacle which attract large numbers to the park. [6] However, as Claire learns compassion for the dinosaurs through her relationship with Owen, her appearance becomes increasingly wild. By the end of the film, she is covered in sweat and mud, with ripped clothes, losing her clinical scientific approach to the animals in favour of an emotional and passionate response, something enhanced by danger, allowing romance to blossom between the pair.

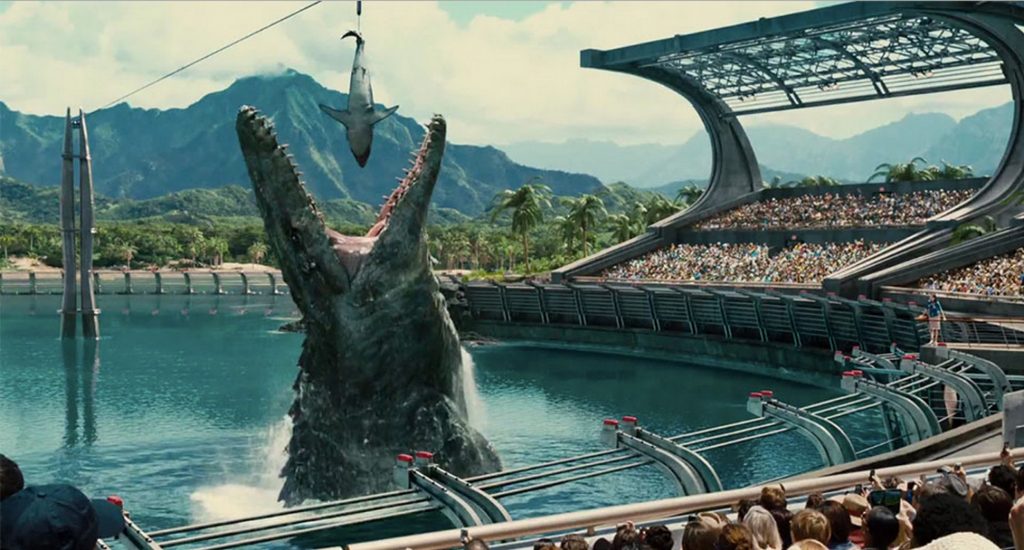

The viewing of animals as spectacle is demonstrated in the scene which depicts the Mosasaurus (a gigantic crocodile-like water dinosaur) feeding show. Park guests, including Zach and Gray, are gathered in a seating arena around a large pool, whilst a commentator/trainer gives information about the animal, before it leaps out of the water to eat a Great White Shark on a hook, soaking the guests. The inclusion of the Shark displays the immensity of the Mosasaurus’s predatory nature, reducing the Shark, an animal highly associated with danger, to prey. This could additionally be a reference to Spielberg’s 1975 thriller Jaws which features a killer Great White, suggesting that the scientific developments in Jurassic World have diminished real animals once deemed scary to objects of food, whilst giving a nod to the first film’s director. This scene also subtly hints at the problems of keeping large, intelligent animals in confined spaces for purposes of spectacle by closely resembling a Sea World show, which feature performing marine animals such as dolphins or orcas. Through documentaries such as Blackfish (2013) these shows have been heavily criticized for their poor treatment of the animals, with Orcas lashing out and killing several trainers. In this way, this scene foreshadows the Indominus’s cunning and seemingly vengeful escape from captivity, as Owen suggests the hybrid dinosaur’s aggression is due to it being poorly raised ‘in isolation’. [7]

While the land of Jurassic World may seem a far flung fantasy to some, there have been real world scientific discussions around de-extinction in recent years. Although dinosaur DNA has been lost to time, there are ongoing debates about the possibility of reviving species which went extinct more recently, such as the Mammoth, Thylacine and Passenger Pigeon. Despite ecological concerns about bringing back species which may disrupt current ecosystems, or not be able to survive the changing climate, many are in favour of resurrecting lost species simply ‘because we think it would be cool to see them’. [8] One of the criteria for de-extinction ‘candidates’ is whether the species is ‘missed’, making de-extinction more about public desire than environmental responsibility. [9] Whilst in Jurassic World ‘no one’s impressed by a dinosaur anymore’, it seems that in reality no one’s impressed by a non-extinct animal anymore. [10] As director Colin Trevorrow states, ‘we live in a cult of the upgrade right now’, ‘We’re surrounded by wonder and yet we want more. And we want it bigger, faster, louder, better’, signifying how scientific development has become about indulgence rather than moral obligation. [11]

Despite the want to bring back long lost animals, there are anxieties about the genetic purity of resurrected species. Brian Switek describes the public ‘distaste for what is “tainted”’, with ‘Persistent and unfounded fears about genetically-modified organisms’ such as GM crops. [12] Switek further points out that ‘The fact of the matter is that revived species would be more akin to carefully-assembled replicas that fit our vision of what those lost creatures were like – living odes to our best conception of what that animal was actually like’. [13] These concerns are prevalent in Jurassic World. The fact that it is the Indominus, the park’s first ‘genetically modified hybrid’ (which Owen describes as ‘no dinosaur’), that is the main cause of disaster in the movie suggests that nature should not be tampered with, the “true” dinosaurs seeming reasonably non-aggressive and content in their enclosures.[14]

However, this argument proves ineffective when head geneticist Dr. Henry Wu states, ‘nothing in Jurassic World is natural’, ‘if [the dinosaur’s] genetic code was pure, many of them would look quite different. But you didn’t ask for reality, you asked for more teeth’. [15] Here, it is clear that fidelity to the original species is arbitrary due to preconceived notions of what dinosaurs should be; the animals being fashioned from public demand rather than scientific realism. In this way, the film defends itself from criticisms that it depicts “traditional” ideas of reptile-like dinosaurs despite recent studies showing that many dinosaurs were feathered and more closely resembled birds. Despite the wonders of technological advancement in the film, Jurassic World takes on a highly anti-technology stance. Technology not only creates the ‘highly intelligent’ Indominus, but subsequently fails throughout the film; the Indominus is able to claw out its electronic tracker, the gyroscope ride is easily smashed by larger dinosaurs placing Zach and Gray in danger, the helicopter trying to take down the Indominus crashes when attacked by Pterodactyls. [16] The technology that allows humans to dominate the animal world is proved inadequate, readjusting the human-animal relationship in the film; what were once creatures of spectacle are now creatures of serious threat, hinting at an over-reliance on technology for safety.

Whilst the dinosaurs destroy technology, they are also viewed as technological creations. This is a view captured by head of InGen’s security operations, Vic Hoskins, who wants to use the dinosaurs as military weapons. When viewing Owen training the Raptors, he asserts that ‘nature gave us the most effective killing machines’, Raptors having an ‘instinct that we can program’. [17] What is more disturbing about these statements is that Vic does recognise the dinosaurs as animals, ‘natural’ beings with ‘instinct’. However he simultaneously demonstrates a complete lack of compassion for these creatures, stating that they ‘have no rights’ and describing how he would ‘terminate the rogues’. [18] Vik proves he views the Raptors as emotionless ‘machines’, when inquiring about their speed and asking ‘ever opened one up, see what they can do?’. [19] Here, Vik’s speech is absent of any ethical issues which would arise from ‘opening [a dinosaur] up’ (presumably killing and dissecting the animal to learn about its capacities). By using a phrase usually applied to vehicles, he demonstrates that he perceives this as no different to inspecting the internal mechanics of a car, simply viewing animals as things which can be used, even in spite of the ‘real bond’ he sees between Owen and the Raptors.[20] Unsurprisingly, as the villain of the film, Vik meets his fate at the jaws of a rogue Raptor.

Vik’s vision is realised when, despite Owen’s protests, the team decide to use the Raptors to take down the Indominus. As day transitions to night this scene becomes literally darker in tone, the Raptors being equipped with night-vision camera headsets to help track the Indominus. In this state, the Raptors become more technologized and vehicle-like as they run alongside Owen’s motorbike, their eyes shining like the headlights in night-vision. Technology once again fails in this scene, the Raptors turning on the humans, when the Indominus (here revealed to be part Raptor) becomes their ‘new alpha’. [21] By technologizing these animals, the humans again lose their authority over them, the bond between human and animal becoming broken.

This is resolved when Owen carefully removes the headset of one of the Raptors after the protagonists become surrounded, thus regaining the animal’s trust, something which also establishes the Raptor’s aversion to this technology. Turning back to the role of killing the Indominus, it is the dinosaurs rather than technology that saves the day, as the Raptors, along with the help of the T. Rex and Mosasaurus are able to defeat the Indominus.

Jurassic World can be seen then as a film with moral intentions. It ultimately teaches us that animals should be seen as animals, rather than attractions or weapons, even when those animals are genetically created, 40ft tall, and full of teeth. Although Owen has a strong connection with the Raptors, he still views them as incredibly dangerous animals. It is his respect and understanding of these creatures which allows him to regain their trust, placing him in the role of the film’s (human) hero, his attitude to animals being presented as the ethical ideal. Furthermore, in light of current discussions around real world de-extinction projects, the film suggests that just because science can bring back these animals, it not necessarily should, especially when the basis for such scientific development is public indulgence. Instead, Jurassic World allows these indulgences to be played out on screen, where we can watch fantasies of man-eating monsters from the safety of a cinema seat.

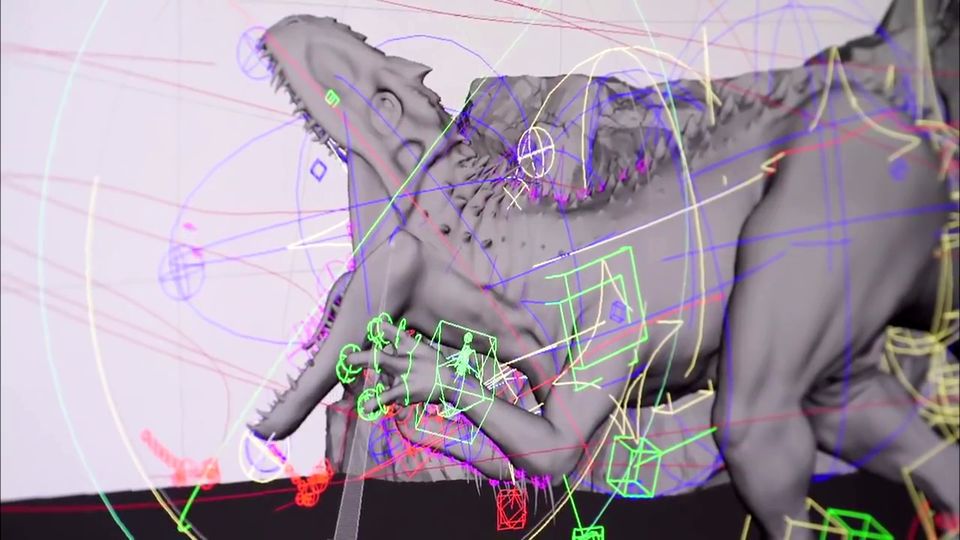

By drawing on motifs from the first Jurassic Park film, part of Jurassic World’s appeal is certainly nostalgic. However Jurassic World is primarily successful because it brings real-world desires and anxieties to light through the medium of cinema and realistic CGI. Despite opposing the use of animals for spectacle or technological purposes, the film can present animals being treated in this way for the pleasure of audiences without becoming complicit in the views it stands against. By relying purely on fantastical CGI animals, the audience is comfortable knowing that “no animals were harmed in the making of this film”.

Bibliography

CG Meetup, ‘JURASSIC WORLD Vfx Breakdown – Dinosaurs’, CG Meetup (2015) <http://www.cgmeetup.net/home/jurassic-world-vfx-breakdown-dinosaurs/> [accessed 21 December 2016]

Dyer, Richard, ‘Jurassic World and Procreation Anxiety’, Film Quarterly, 69.2 (2015) <http://fq.ucpress.edu.eresources.shef.ac.uk/content/ucpfq/69/2/19.full.pdf> [accessed 21 December 2016]

Grates, Sara, ‘SeaWorld-Owned IP Address Linked To Majority Of Votes In Newspaper’s ‘Blackfish’ Poll: Report’, The Huffington Post (2014) <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/01/03/seaworld-blackfish-poll-rigged-ip-address_n_4537254.html> [accessed 21 December 2016]

Jurassic World, ‘Jurassic World Owen and Blue/The Raptors Attack The Irex’, Movies2You (2016) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SOnJnKXavyQ> [accessed 21 December 2016]

MacPhee, Ross, ‘The Science Behind De-extinction’, American Museum of Natural History (2013) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pkc_WodJxsk> [accessed 21 December 2016]

McGovern, Joe, ‘Colin Trevorrow on ‘Jurassic World’s monster star Indominus Rex’, Entertainment Weekly (2015) <http://ew.com/article/2015/05/25/meet-new/> [accessed 21 December 2016]

Phillips, Ian, ‘The velociraptors in the ‘Jurassic Park’ movies are nothing like their real-life counterparts’, Business Insider UK (2015) < http://uk.businessinsider.com/what-velociraptors-look-like-2015-5?r=US&IR=T> [accessed 21 December 2016]

Brian Switek, ‘The Promise and Pitfalls of Resurrection Ecology’, National Geographic (2013) <http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2013/03/12/the-promise-and-pitfalls-of-resurrection-ecology/> [accessed 21 December 2016]

Switek, Brian, ‘Reinventing the Mammoth’, National Geographic (2013) http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2013/03/19/reinventing-the-mammoth/ [accessed 21 December 2016]

Filmography

Blackfish. Dir. Gabriela Cowperthwaite. Magnolia Pictures, 2013

Jaws. Dir. Steven Spielberg. Universal Pictures, 1975

Jurassic Park. Dir. Steven Spielberg. Universal Pictures, 1993

Jurassic World. Dir. Colin Trevorrow. Universal Pictures, 2015

Further Reading

Crichton, Michael, Jurassic Park (London: Arrow Books, 1991)

De Semlyen, Nick, ‘Safety Not Guaranteed’, Empire (2015) <http://www.jurassicworlduniverse.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/20150601-empire.pdf>

Edwards, Richard, ‘Jurassic World: Chris Pratt Goes Walking With Dinosaurs’, SFX, Vol.262 (2015) <http://www.jurassicworlduniverse.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/2015summer-sfx.pdf>

Shapiro, Beth, How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016)

[1] Jurassic World. Dir. Colin Trevorrow. Universal Pictures, 2015.

[2] Jurassic World.

[3] Jurassic World.

[4] Richard Dyer, ‘Jurassic World and Procreation Anxiety’, Film Quarterly, 69.2 (2015) http://fq.ucpress.edu.eresources.shef.ac.uk/content/ucpfq/69/2/19.full.pdf [accessed 21 December 2016] (p.20).

[5] Jurassic World.

[6] Jurassic World.

[7] Jurassic World.

[8] Brian Switek, ‘The Promise and Pitfalls of Resurrection Ecology’, National Geographic (2013) http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2013/03/12/the-promise-and-pitfalls-of-resurrection-ecology/ [accessed 21 December 2016] (para.9 of 17).

[9] Switek, ‘The Promise and Pitfalls of Resurrection Ecology’ (para.4 of 17).

[10] Jurassic World.

[11] Joe McGovern, ‘Colin Trevorrow on ‘Jurassic World’s monster star Indominus Rex’, Entertainment Weekly (2015) http://ew.com/article/2015/05/25/meet-new/ [accessed 21 December 2016] (para.2-5 of 11).

[12] Brian Switek, ‘Reinventing the Mammoth’, National Geographic (2013) http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2013/03/19/reinventing-the-mammoth/ [accessed 21 December 2016] (para.5 of 16).

[13] Switek, ‘Reinventing the Mammoth’ (para.4 of 16).

[14] Jurassic World.

[15] Jurassic World.

[16] Jurassic World.

[17] Jurassic World.

[18] Jurassic World.

[19] Jurassic World.

[20] Jurassic World.

[21] Jurassic World.