I suspect humans are the only animals that know the inevitability of their own death. Other animals live in the present. Humans cannot. So they invented hope.

-Young Woman

In its essence, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is a film about the significance of memory and how certain factors can impact how we remember our lives. It is an undoubtedly complex film that purposefully works to isolate and confound the viewer in regard to both its narrative and themes. When viewing the film within the context of Kaufman’s broad range of work however, we can begin to piece together his recurrent themes within the context of analysing animals in film. Doreen Alexander Child writes that Kaufman’s writing typically features characters “isolated in their own existence”: such as Human Nature (2001), a comedy drama that features an ape-like man amidst the concept of civilisation. Kaufman is renowned for characters with an inability to “step out of themselves”, as Alexander Child describes, and this trait often generates their unusual relationships with animals. While Human Nature seems like an obvious choice for analysing human-animal relationships, I am interested in how Kaufman directs animals in a more subdued- yet unconventionally peculiar – display of the possibilities of film and narrative.

The film is an adaption of Iain Reid’s novel of the same name, written for the screen and directed by Kaufman. To recount the narrative as we may attempt to understand it, a Young Woman [as referred in the script] and her recent boyfriend Jake are driving to meet Jake’s parents at their house for dinner. It becomes immediately apparent that the Young Woman is not entirely engaged in her relationship, and she heavily contemplates ending it. This resigned awkwardness leads to the night collapsing into an absurdist inventory of Jake’s memories across time, with the Young Woman’s own identity and existence becoming increasingly tenuous. Interspersed throughout this ordeal, shots of an older man [the Janitor] performing janitorial work at a local high school are implied to be viewed as the present version of Jake. From this it becomes increasingly obvious that this older Jake is composing an imaginary relationship with the Young Woman as an anachronistic, and ultimately failing, attempt to revitalise his dreary life. Animals weave between conversation, television screen, and memory; changing form constantly to match the reality that the Janitor is presenting to us. Each animals’ role in the film is to represent an aspect of Jake’s internal psyche, ventriloquised across form, genre, and chronology.

There is something dreary and sad in here. And it smells. I wonder what it must be like to be a sheep. Spend one’s entire life in this miserable, smelly place doing nothing. Eating, shitting, sleeping over and over…

-Young Woman

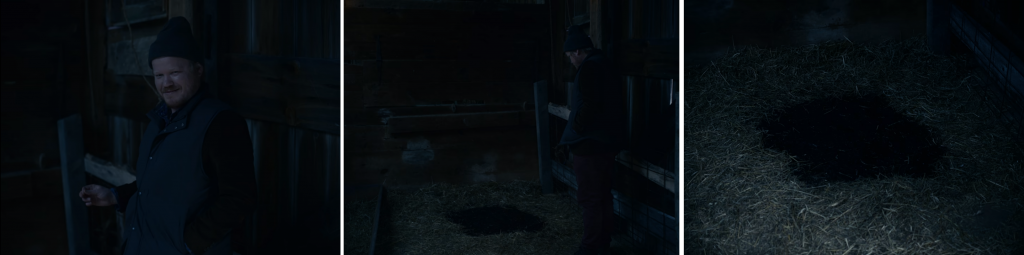

Kaufman takes an existentialist perspective on mortality, posing the question of an animal’s apparent lack of awareness of death in comparison with the burden death places on humanity. The scene consists of Jake and the Young Woman touring the family’s barn after exiting the car. The Young Woman notices a pile of lamb carcasses and asks what will happen to them, confusing Jake who replies that they’re “already dead” and frozen solid. The interaction is slightly awkward to watch, following the uncomfortable conversational style for the entirety of the film, but this time there is an added layer of sinister unease. Jake’s apparent confusion and responding frankness regarding death conflicts heavily with the distressing sight of the lamb’s corpses. The blocking of the conversation is also unconventional: with the Young Women placed to the right in the foreground, turning her back to the viewer to address Jake who restlessly fidgets in the background.

Towards the end of the scene, as the couple brace the dreary winter wind, the Young Woman delves into her internal monologue to fittingly contemplate the nature of death. She interprets the “uniquely human” experience of registering the “inevitability of [our] own deaths,” and concludes that this awareness inherently builds in us a need for optimism and hope in the face of this impending deadline. What is most intriguing is that the Young Woman signifies this experience by singling out humans as unique to animals. We can relate this thought process to what Cary Wolfe defined as the “fundamental repression” of nonhuman subjectivity. Wolfe’s writings on our cultural understanding of animals describes the “embeddedness and entanglement of the ‘human’ […] in all that used to be thought of as its opposites or its others”. The Young Woman describes the sheep’s lives as miserable and smelly, consisting of meeting base functions with little else to occupy them. Though this may seem like a negative description, we follow the Young Woman as she internalises the concept of a life lived entirely in the present. Ironically, as the Young Woman is an image conjured by the Janitor, she herself can exist solely in the present. We see this through her multiple identity changes (name, occupation, outfit) which are not questioned or explained but readily accepted by her. As viewers we then can begin to associate her fleetingly tenuous identity within the context of her musings on animal identity. By separating the humanness from herself, she is able to identify more readily with the barn animals who are free from humanistic labours of life. Kaufman leaves it purposefully unclear as to what she concludes, and as viewers we are forced to reflect on this conundrum in the bleary darkness of our mirrored screen.

Coming home is terrible. Whether the dogs lick your face or not.

-Young Woman

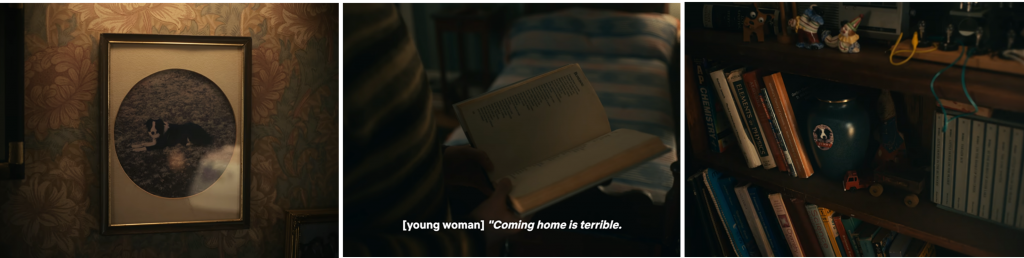

As well as animals signifying specific themes in the film, Kaufman also uses animals to represent a character’s unreliable perspective. Jake’s childhood dog, Jimmy, makes sporadic appearances during the film’s second act and works to symbolise Jake’s distorted memory of his childhood home. Jimmy appears in a constant state of shaking out his fur, making for a series of disturbing shots of his aggressively oscillating head and agitated whimpers. An interaction between Jimmy and the Young Woman has Jimmy placed slightly out of the frame beneath the Young Woman’s grappling arms; the only indication of his presence being the ferocious sounds of him shaking his body. Jake forcefully apologises for Jimmy’s wetness, and we jarringly jump to a pulled out shot of the Young Woman crouched over with no Jimmy present. Jake apologises again for the smell which the Young Woman nonchalantly excuses with, “he’s a dog”.

In a later scene, the Young Woman is inspecting ‘Jake’s childhood bedroom’ and on a bookshelf we see an urn marked with Jimmy’s name and photograph. Browsing the horde of books and films, the Young Woman notices a book open on a page with the Eva H.D. poem, “Bonedog”: a poem that she recited as her own earlier in the car. The strange sequences of Jimmy’s appearance, when combined with the wider context of the narrative, form a valuable insight into the way memories of animals are expressed in film. Jake appears physically uncomfortable by even the mention of Jimmy’s presence, and his insistent apologies disguise a more pressing need for the Young Woman to stop drawing attention to what is clearly upsetting for him to remember. What is particularly intriguing is the specific way that Jake forms his memory of Jimmy. The present-day Jake can most easily recreate still images of Jimmy as his portrait is still hung in the family home where he lives. However, the physical conjuring of Jimmy occurs only when Jake can picture him completing the most physically intense action. Kaufman does this to imply that our recollection of animals is dictated by kinetic and sensory memories. What Jake remembers of Jimmy is his wet-dog smell and his shaking body, and so these are the most prominent actions that he is able to recreate, a fact he is visually ashamed and embarrassed of.

It’s not bad. Once you stop feeling sorry for yourself because you’re just a pig, or, even worse, a pig infested with maggots. Someone has to be a pig infested with maggots, right? It might as well be you. It’s the luck of the draw.

-The Pig

One of the most prominent animal presences in the film is the recurring image of the maggot-infested pig which provides much of the film’s conventional horror motifs. This sequence also takes place in the barn as Jake recounts that “life isn’t always pretty on a farm,” and goads the Young Woman into asking why the family’s pigs had been put down. There is a sinister ambience in the darkness of the barn that is emphasised with whistling wind, creaking wood, and the occasional bleating sheep. Jake is framed staring directly at the viewer as isolated strings blend into the soundscape, building chromatically to punctuate the tension of the scene. When it is revealed that the pigs’ stomachs were being eaten alive by maggots, the strings reach a discordant note, and a shot of the dark stained hay is overlayed with a quiet – but nonetheless nauseating – squelching sound. Jake repeats a grim iteration of his earlier line, stating “life can be brutal on a farm”. The whole sequence is unnerving and draws on elements of horror to generate a tone that moves the film from the awkward philosophising in the car, to something much more unsettling. There is also a strangeness in the indescribable feeling of absence in the scene; instead of pigs we are given a pig shaped hole. Instead of disgust, the Young Woman appears indiscernibly pensive, and Kaufman abruptly stops the strings as Jake announces they should make their way inside.

We are not free from this torment just yet, however, as images of pigs appear garishly through the next scene as Jake and the Young Woman enter the house. Each shelf is stacked with antique trinkets, pigs standing out as the most common porcelain effigy. It is as if Kaufman is forcing us to remember the disgust of the previous scene as the Young Woman cautiously eyes the collection of items and furniture around the room. As the family settle down to eat, Jake’s mother comments that all of the food is home made. A slow pan down reveals the joint on the table is ham, accompanied by charming salt and pepper pot pigs. The Young Woman sends a look of slight confusion to Jake which is met with his ignorant stare. In the chronology of the film, this marks one of the most explicit disorientations of time. The pig exists both as an absent mass of remembered carrion and as a mound of succulent flesh upon a dinning table.

Despite its grisly association, this moment – this pig – signifies the film’s shift from conventional horror to a more stylised surrealism. The pig is reprised again in the third act’s dreamlike sequence as the Janitor’s memories and formations merge into a surreal expression of his internal disintegration. Anat Pick describes a pattern in animal films of “alternating between a poetic surrealism and a violent realism”, we see this expressed explicitly in the image of the pig which Kaufman elevates from gruesomely mundane to artistic abstraction. Faced with the extent of his delusion, the Janitor descends into a state of delirium and begins paradoxically undressing in his snowed-in truck. Appearing before him through the windshield, an animated pig emerges from the snow. As the pig stands, maggots and blood falling from its undercarriage, the Janitor exists his car and follows it into the high school, fully nude. The scene is backed by a mixture of non-diegetic music; the classic sinister strings from earlier accompanied by a garbled 1950s television jingle. The combination of sounds creates a hallucinatory disjoint of tone and adds to the oddity of the scene. Although inherently strange, this is not a moment of absurdist horror. Walking the school corridors, the pig and the Janitor converse as if old friends. The pig itself is charmingly cordial and acts as a kind of ghostly guide; disregarding the film’s previous existentialist commentary on mortality to instead offer a more adaptably optimistic nihilism. Kaufman offers a bizarrely outlandish voice of reason that anchors the film before the final scene, and the Janitor’s assumed death. Finding our voice of reason in this animated re-animated pig corpse encourages us to identify with the pig in a film that purposefully isolates us from its narrative, characters, and message.

Eh. I’m just evolving. Even now, even as a ghost, as a memory, as dust. As you will. Everything is the same. When you look close enough. You, me, ideas. We’re all one thing.

– The Pig

Kaufman’s use of animals appears subconsciously pivotal to our dissecting of the narrative and its themes. Through the frozen lamb corpses, Kaufman offers a chance to identify ourselves and our mortality with the mortality of others. This generates questions about animal sentience regarding death and we can begin to develop an understanding of how animals will be considered in the film. The fragmented appearance of Jimmy, Jake’s dog, presents an idea as to how our memories of animals are depicted in film and how the emotional association of the animal affects its depiction. Blending media and genre, Kaufman’s pig enables us to analyse our perception of animals across form. Taking the form of story, advertisement, food, and animated guide, the pig’s image transcends the boundaries of its physical body and adapts its own significations of theme and narrative. Through film, animals are given opportunities outside of their usual barrier of agency and Kaufman encourages us to embrace these possibilities.

Figures 1-28 are stills taken from Kaufman, Charlie, dir., I’m Thinking of Ending Things (Netflix, 2020)

Bibliography

- Alexander Child, Doreen, Charlie Kaufman: Confessions of an Original Mind, (ABC-CLIO, 2010) Proquest Ebook Central eBook

- Kaufman, Charlie, dir., I’m Thinking of Ending Things (Netflix 2020)

- McNeal, Fiona, bonedog peom from i’m thinking of ending things, online video recording, Youtube, 6 September 2020 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjdhgyLxkJo&t=3s> [accessed 11/01/23]

- Pick, Anat, Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011) EBSCOhost eBook

- Wolfe, Cary, Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) Proquest Ebook Central eBook

Further Reading and Viewing

- Gondry, Michel, dir., Human Nature (Fine Line Features, 2001)

- Gondry, Michel, dir., Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Focus Features, 2004)

- Jonze, Spike, dir., Being John Malkovich (Universal Pictures International, 1999)

- Moine, Raphaelle, ‘From Surrealist Cinema to Surrealism in Cinema: Does a Surrealist Genre Exist in Film?’, Yale French Studies, 109 (2006) 98-114 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4149288> [accessed 11/01/23]

- Romney, Jonathan, ‘”That’s Always My Goal, To Put People Off”: An Interview with Charlie Kaufman’, Sight and Sound, 40.8 (2020) 34-39 <https://www.proquest.com/magazines/thats-always-my-goal-put-people-off-interview/docview/2684653263/se-2?accountid=13828> [accessed 11/01/23]