In Henry Kosta’s film Harvey (1950), the simple power of the imagination, entwined with the light-hearted childish nature of the protagonist Elwood P. Dowd (James Stewart) acts as a tool to undermine and distinguish the evident psychological disturbances that lie beneath the surface of the plot. Harvey, a six-foot three-and – a – half – inch tall hare, is only visible to his ‘companion’ Elwood, who regularly dines with and introduces Harvey to friends and family. Despite its comic genre and slapstick nature, there is one scene that stands out to show the somewhat disturbing nature of Elwood’s deranged mind. In the ‘Two Martinis’ scene, Elwood guides Harvey into a bar, a space which is regularly associated with the over consumption of alcohol, a probable cause of the protagonist’s projections, and continues to converse with him and the other members of the bar. Although it being a seemingly harmless moment, it leads us to question why might background characters, such as the barman, entertain Elwood’s obvious psychological deterioration. During the scene, the camera pans across the bar, and switches to Elwood’s point of view (POV), giving the allusion that we, and everyone else, can see Harvey. This use of camera angle almost transforms Harvey into a part of the mis-en-scene, drawing our attention into his character, and his relationships with Elwood. The Camera angles force us as the audience to become very aware of Harvey’s physical space in the scene and character.

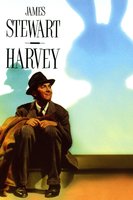

Fig 1 – Harvey being guided across the busy road

As seen in the picture, Elwood physically rushes back to guide Harvey across the road. The opening to this scene functions to enhance the over exaggerated relationship between the pair, thus furthering our empathy for Elwood, whilst at the same time concealing the perturbing nature of the ‘friendship’. Elwood considers Harvey as if he were a child, notably telling Harvey, subsequent to escorting him across the road, that he ‘must be more careful’, as if he were instructing an infant. In this moment, due to the paternal forces of expression that Elwood evokes, we experience the birth of the heart warming union between man and his imagination. This union thus prompts a certain pathos towards protagonists delusion.

Fig 2 & 3 – Elwood speaking to Harvey, and public reaction

When Harvey and Elwood are in the bar, he converses with Harvey as if he were any other physical being. He asks him where he would like to sit, and if he is comfortable. As the camera pans round, it begins to zoom into where Harvey would be sitting, on the bar stool next to Mr Dowd, and then cuts straight to a shot of a man sitting at the bar, with a confused and surprised face. Here, Kosta’s cinematic skills actually produce a somewhat comic effect, rather than the expected unnerving reaction that one might experience the same situation in real life. These reactions continue to lead us to question why is there such a difference in social standards in terms of mental illness in film and reality? Whilst at the same time, emphasizing the need for an appreciation for the imagination and the preservation of childishness. This conflict between childishness and mental health acts as a paradox which seemingly cannot be resolved, which only strengthens the emotive pathos we feel towards Elwood more.

Fig 4 – Comic juxtaposition between Elwood and the Gentleman at the bar