Set in 1988, Richard Kelly’s popular cult classic Donnie Darko deals with the teenage title character’s battle with diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia, fits of violent behaviour, and cynicism towards established institutions. Unlike other ‘ordinary’ 16 year olds, Donnie (Jake Gyllenhaal) has thoughts that are plagued by a man-sized rabbit (James Duval) that simultaneously saves him from, and then dooms him to, death by a falling jet engine. Frank “the bunny” plays a crucial role in the advancement of the filmic narrative by teaching Donnie about the laws of time travel, and on the way, manipulating him to carry out a series of crimes that circumstantially teach him valuable lessons about himself and other characters around him. Being a human in a sinister rabbit costume, Frank’s mannerisms do not necessarily correlate with the familiar, stereotypical characteristics we typically associate with “bunny rabbits”. His frightful appearance, desire for destruction and un-rabbit-like nature of his behaviours are what single him out from other filmic representations of this species and make him a bewildering human/animal character.

This indie film classic avoids the categorization into one specific genre, and instead adopts the themes of several. With doomsday looming, a haunting 6ft rabbit and a psychologically troubled protagonist, one is not unlikely to mistake Donnie Darko as a psychological thriller, or horror film. However, the teen romance between Donnie and Gretchen, the heavily significant physics-based inclusion of time travel, and hilariously pithy dialogue allow Kelly to weave elements of the romance, science fiction, coming-of-age and comedic genres seamlessly into the film’s main plot structure. This refusal to adhere to typical genre specific conventions is what allows Frank’s character to have so much significance in deciphering the film’s intended meaning or direction – he not only acts as a guide for Donnie, but also for the somewhat disorientated audience also. Whether we decide to view Frank as an imaginary friend, a religious guardian or a manifestation of Donnie’s paranoid schizophrenia, it not only significantly changes the destiny of the title character, but also alters the generic understanding of the entire film. Although Frank is in fact human, and is essentially boyfriend to Donnie’s sister, until the film’s finale, the audience only ever witness Frank as Donnie’s menacing rabbit companion who can only be seen by Donnie himself. With this Frank, as a symbol of the rabbit species, becomes an extremely crucial aspect of the film’s plotline.

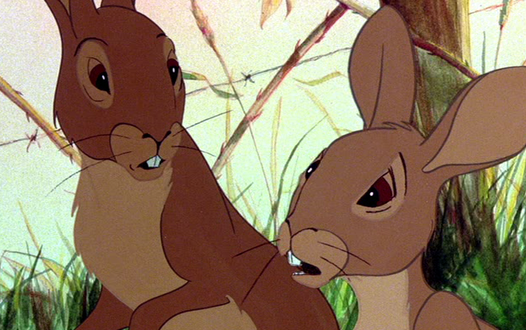

Frank and Watership Down

When researching ‘Frank the rabbit’s’ character, there is an abundance of speculation surrounding the direct significance of his “rabbit-ness”, but not necessarily any fact. The most concrete information I learnt about Kelly’s choice of animal was from a transcribed interview with the director himself who revealed that when deciding the Halloween costume Frank would be wearing he ‘immediately thought of a Rabbit’ as he planned ‘to make a literary reference to the novel “Watership Down”’. Kelly goes on to comment that there is ‘a real irony in a rabbit being this fragile animal, one of natures’ most innocent and harmless creatures’ and to have Frank as ‘a monstrous version of this’ meant that, for him, ‘it came to a point, where due to the irony, it had to be a rabbit’.[1]Understandably, it makes quite a bit of sense for Frank to be based upon Watership Down’s Fiver, as he too can predict destructive forces ahead and warns the others in his warren of the looming danger approaching them, as Frank warns Donnie of the end of the world. However, like Kelly identifies, Frank is a ‘monstrous version’ of these commonly adored, ‘innocent’ animals, so for Donnie, and us as an audience, this is something that separates Frank from the other characters of his species.

Donnie himself brings to light the confused understanding of rabbits in this film when he speaks out in his class about the species in Watership Down. Donnie confirms that he believes ‘the death of one species is more tragic than another’ (human/rabbit), and admits that despite this, ‘he likes rabbits’ because ‘they’re cute and they’re horny’.[2] The irony that Kelly desires to create through Frank’s character is extremely prevalent during this scene. It is obvious to the audience that Donnie’s concern here is not with the problems faced by the rabbit’s in Watership Down, but the singular rabbit that torments his day-to-day thoughts. Donnie directly draws attention to the cultural stereotypes often associated with rabbits, as merely ‘cute’ and ‘horny’, which, as Kelly addresses, is the complete opposite of Frank’s ‘monstrous’ and destructive nature. Donnie also expresses a concern with ‘mourn[ing]’ the species ‘like it was human’, which directly addresses his confusion regarding the legitimacy of Frank’s human/animal species. Why should he trust the word of Frank ‘the rabbit’ over the word of Frank ‘the human’? Does his species make a difference to the value of his life? Should Donnie feel guilty or upset that in the end, he knows he must kill Frank? These are the questions that Kelly himself poses to his audience, ultimately forcing you to decipher your own interpretation of Frank’s mysterious, ‘monstrous’ animal appearance.

Frank as a Supernatural Entity

In disagreement with Donnie’s devaluation of a rabbit’s life over a human’s, his love interest, Gretchen, replies ‘you’re wrong. These rabbit’s can talk, they’re a product of the author’s imagination and he cares for them, so we care for them’.[3] Gretchen’s attitude towards these animal characters is based upon the condition that these specific fictitious rabbits ‘can talk’. In this case, Frank also fits this description; yet, dissimilar to the rabbits we hear in the excerpt from Watership Down, Frank’s voice is not one we commonly associate with everyday human speech. Throughout the film, Frank’s vocals are made up of several layers of recorded dialogue that are spoken by James Duval at different volumes and pitches. These layers are then placed on top of one another to create a raspy, unfamiliar and somewhat unnerving voice. Randolph Jordan believes that this ‘aesthetic strategy’ was applied by Kelly to establish Frank’s ‘status as a supernatural entity’ as this method ‘emphasizes the connection between Frank and the divine intelligence as entities distinct from Donnie’.[4] This auditory technique not only sets Frank aside from Donnie, but also from the characters within Watership Down, suggesting that as a kind of rabbit/human hybrid, Frank spiritually and religiously exceeds the cartoon rabbits we observe on the television screen in Donnie’s English class. This also adds to the idea that Donnie must die in order to save Frank, ultimately favouring Frank’s human life over his rabbit one, which he murders outside the home of Roberta Sparrow (Patience Cleveland). Interestingly, the Frank we see getting out of the car at this point of the film does not have this eerie layered voice like the Frank we are used to hearing speak to Donnie throughout the film. This emphasizes the transformation from human to human/animal Frank experiences when entering the alternate reality.

Frank and Childhood

Alternatively, Frank is referred to by several of the other characters in the film as Donnie’s “imaginary friend,” drawing attention to Donnie’s inner child. An “imaginary friend” is something that is usually associated with children, which is why it may be deduced that Kelly’s choice to make Frank a giant bunny rabbit is a means of illustrating Donnie’s desire to transgress back to a simpler, more childlike state. When under hypnosis during therapy sessions, Donnie reverts to using a childlike voice and looks to a stuffed toy dog for comfort when speaking of things that worry him. These actions reveal a childish side to Donnie that may find comfort in an imaginary, human-like animal such as Frank.

Similarly, if Frank is a manifestation of Donnie’s childhood nostalgia, he can also be likened to Lewis Carroll’s White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland. Both rabbits are under very strict time constraints, the White Rabbit to get to the short tempered Queen of Hearts, and Frank to teach Donnie the laws of time travel before the end of the world. Analogously, the rabbit hole in which the White Rabbit leads Alice is somewhat similar to the wormhole Donnie is led to by Frank; both portals take the trusting ‘children’ to an alternate reality, only, one is a rabbit’s home and the other a scientific discovery. Both rabbits can walk on two legs, talk, reason and hold values and natures more comparable to humans than rabbits, however, their non-threatening animal façade is what makes them curious to the protagonists, and it is this curiosity that permits the narrative progression.

Equally, what distinguishes Frank from Alice’s White Rabbit is his gruesome, un-childlike irregularity, which makes him somewhat opposite to Carroll’s cuddly bunny. As a reversal of the White Rabbit, Frank would thus be seen as a visual manifestation of Donnie’s loss of childhood as opposed to a step back into it. The unfamiliarity and contorted representation of Frank’s rabbit form can be interpreted as a transformation from Donnie’s innocence in childhood to a confused and, in Donnie’s case psychologically disturbed, adolescent form. A destruction of childhood is represented in other aspects of the film such as when the well-loved Jim Cunningham is found to have child pornography in his home, and the allusion to Donnie and Gretchen losing their virginity at the Halloween party. A protagonist’s transformation into adulthood is a crucial aspect of the coming-of-age narrative, and thus, it is the destructive behaviours encouraged by Frank, the psychological stress that brings about Frank’s appearance and Donnie’s ultimate ‘suicide’ that occurs before he reaches adulthood that demonstrate the damaging impact childhood can have on a young person’s development.

Frank’s entire character is based upon the complete reversal of cultural stereotypes we believe universally define rabbits as a species. His character is creepy, not cute, giant, not small, bizarre, not familiar, destructive not reproductive. And as the only animal representation in the film, we as an audience are forced to attempt to comprehend his significance by employing our own understanding of this domesticated species to his demeanor. Yet, our attempts become futile when we learn that Frank is in fact human. With this in mind, Frank’s humanness is what connects him to Donnie, whether he is a figment of his imagination, or a character living amongst the manipulated dead, Frank’s destructive human nature unites him with Donnie and separates him from other rabbit characters used in the development of a filmic narrative, such as Watership Down and Alice in Wonderland. Although both Fiver and the White Rabbit share anthropomorphized qualities with Frank, such as speech, reason, and the concept of time, they are animated creatures that still hold the stereotypical ‘cute’, ‘innocent’ and ‘fragile’ characteristics that Frank, played by a real-life human, does not.

As confusing as Donnie Darko’s may be, one can breathe a sigh of relief that it is the audience’s own interpretation of Frank’s animality that forms the significance of his character. Without a true explanation of his ‘rabbit-ness,’ other than the fact that it’s an ironic twist on the literary inclusion of Watership Down, our individual interpretations of Frank’s bizarre character is what form’s our own understanding of the film’s definitive meaning. Whether you believe the giant rabbit to be a manifestation of Donnie’s schizophrenia, a divine spirit, or a human/rabbit time traveller, the film’s genre, and thus overall significance, is whatever we want it to be.

[1] Nik Higgins, Richard Kelly (Future Movies, 2002), https://www.futuremovies.co.uk/filmmaking/richard-kelly/nik-huggins [accessed 14 January 2017]

[2]Caecus Veritas, Donnie Darko Bunny Discussion (YouTube, 2006) https://youtu.be/NAryr1htkDM[accessed: 12 January 2017]

[3]Caecus Veritas, Donnie Darko Bunny Discussion (YouTube, 2006) https://youtu.be/NAryr1htkDM[accessed: 12 January 2017]

[4]Randolph Jordan, ‘The Visible Acousmêtre: Voice, Body and Space Across the Two Versions of Donnie Darko’, Music, Sound, and the Moving Image, i, 3 (2009), 47–70 http://online.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk.eresources.shef.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.3828/msmi.3.1.3 [accessed 4 January 2017] (p. 53-4)

Suggested Further Reading

Adams, Richard, Watership Down (any edition)

Beck, J. C., ‘The Concept of Narrative: An Analysis of Requiem for a dream(.com) and Donnie Darko(.com’, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, iii, 10 (2004), 55–82 http://journals.sagepub.com.eresources.shef.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1177/135485650401000305

Jordan, Randolph, ‘The Visible Acousmêtre: Voice, Body and Space Across the Two Versions of Donnie Darko’, Music, Sound, and the Moving Image, i, 3 (2009), 47–70 http://online.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk.eresources.shef.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.3828/msmi.3.1.3

Booth, Paul, ‘Intermediality in Film and Internet: Donnie Darko and Issues of Narrative Substantiality’, Journal of Narrative Theory, iii, 38 (2008), 398–415 http://www.jstor.org.eresources.shef.ac.uk/stable/pdf/41304894.pdf

Bibliography

Donnie Darko. Dir. Richard Kelly. Newmarket Films, 2001.

Higgins, Nik, Richard Kelly (Future Movies, 2002), https://www.futuremovies.co.uk/filmmaking/richard-kelly/nik-huggins [accessed 14 January 2017]

Jordan, Randolph, ‘The Visible Acousmêtre: Voice, Body and Space Across the Two Versions of Donnie Darko’, Music, Sound, and the Moving Image, i, 3 (2009), 47–70 http://online.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk.eresources.shef.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.3828/msmi.3.1.3 [accessed 4 January 2017]

Murray, Rebecca, Inside ‘Donnie Darko’ with Writer/Director Richard Kelly (About.com, 2012), http://movies.about.com/cs/donniedarko/a/donniedarkork.htm [accessed 5 January 2017]

Taylor, Trey and Dazed, How Donnie Darko’s Frank Became the Ultimate Outsider Symbol (Dazed, 2016), http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/33431/1/how-donnie-darkos-frank-became-the-ultimate-outsider-symbol [accessed 4 January 2017]