“A city girl like you? You wouldn’t last five minutes, love. This is a man’s country out here.”

– Mick Dundee (Paul Hogan)

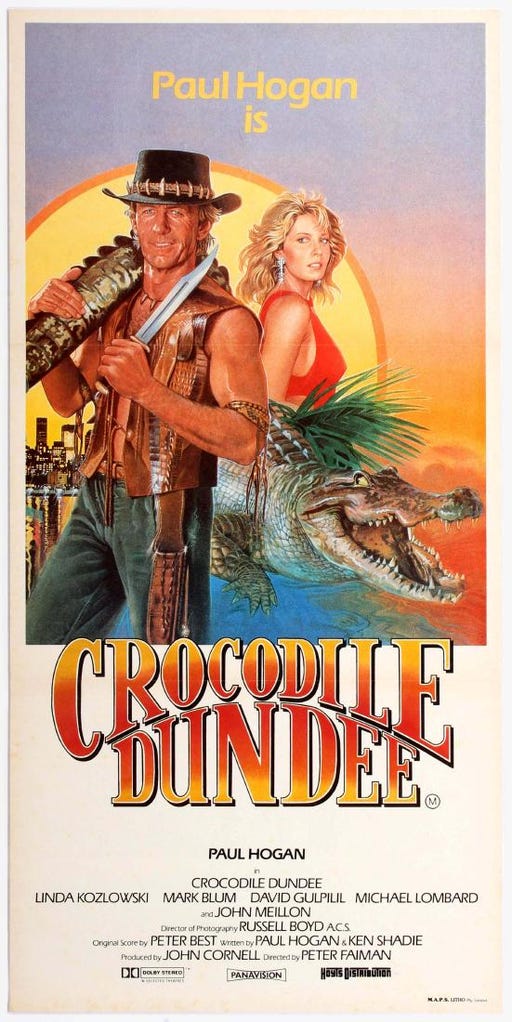

Crocodile Dundee is a 1986 action/comedy film, following the character of Mick Dundee (Paul Hogan), nicknamed “Crocodile” after being mauled by a crocodile, an Australian bushman, as he meets his eventual love interest, New York journalist Sue Charlton (Linda Kozlowski) in the outback. Animals are used to code gender roles and explore masculinity and femininity; throughout the film, Mick frequently exercises dominance in his interactions with animals, aligning his uncouthness and ‘wildness’ with his fierce masculinity and as a figure of strength and power. Sue, as the urban woman, acts as a contrast to his ‘wildness’, coding her refined and passive persona as being something overtly feminine. He returns to New York City in the second act of the film, wherein he attempts to adapt to urban life in America.

Belonging to the action-comedy genre, much of the generic threats within the narrative are generated by the presence of exotic bush wildlife. There is a romantic subplot between Sue and Mick, meaning that the animals in the narrative not only serve to characterise Mick as a feral master of the bush but also as tools to bring the pair together. The incongruence of the urbane Sue wandering the treacherous wilderness, only to be saved by the mythic-man-of-the-land Mick Dundee creates tension but also comedy, as the film encourages laughter at her ill-suitedness to the bush. Mick is also displaced in the second act, however, the self-preserving masculinity that serves him in Australia also allows him to triumph in New York City – Dundee conquers both the animals of the outback and the mean streets of NYC, winning Sue’s affections.

By displaying Mick as masterful of the land around him, Faiman engages with the idea of ‘the one man who stands above the rest — above the natural world…. [and] above the dangers of both the mythologised outback and New York high society’ [1]. Dundee comes from the tradition of the hyper-masculine, croc-wrestling ‘larrikin’ – an Australian stereotype of a boisterous man [2], such as Mick, who in this case, who seeks to express his exuberant masculinity through his dominance of the unforgiving Australian flora and fauna. His rumbustious personality is explored through his relationship with the natural world. Anouk Lang discusses the long history of Australian masculinity being associated with animals as a result of colonisation, resulting in cultural folklore that ‘the mastery of animals is metonymic of the mastery of the land.’ [3] . By proving yourself in control of your challenging surroundings, you prove yourself as being a Herculean figure of optimum masculinity to be revered and desired. The bush is the birthplace of truly authentic Australian males.

The presence of animals – especially those stereotypically associated with the untamed Australian bush such as the eponymous ‘crocodile’ – is key to establishing the gender roles of Mick and Sue.

Mick is seen to wear animal products on himself to signify his physical strength and his triumphs over the animal world. For much of the film he wears a crocodile skin vest and animal teeth adorn his necklace and hat (fig. 1). The use of decorative animal products becomes totemistic, symbolizing the beasts that Mick has conquered through his own masculinity; though the animal is not physically present, its estranged body parts signal the brute force and deadly human-animal relationship that exists between Mick and the creatures of the outback – by being reduced to skin and teeth, the image of human triumph over dangerous animals has an implicit presence in every scene he appears in. The animal parts become fused with his own identity, and he takes on the symbolic characteristics associated with fierce outback creatures – physically threatening. The looming figure of the slaughtered crocodile that follows Mick throughout the film serves as a reminder of the true wildness that inhabits him.

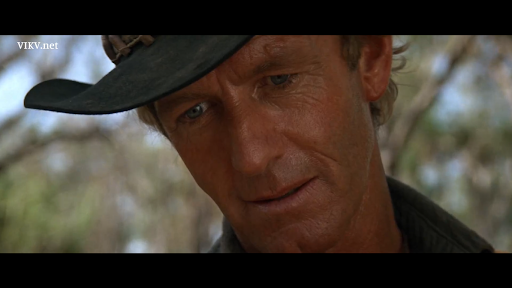

Fig. 2

Fig, 3

The animals surrounding him become tools for the film to demonstrate Mick’s alignment with the animal world; At 14:20, Mick engages with a water buffalo that is blocking their path and successfully hypnotizes it, subduing the creature without using brute force. In these two images (figs 2 and 3), we see a tender side of Mick in his relationship with animals, as he tames the creature through human touch and soothing noises, with Faiman using the idea of the ‘animal gaze’. Several shot reverse shots swap between the head of the buffalo and a slow zoom into Mick’s own eyes, emphasising the power of his gaze.

Jonathan Burt discusses the concept of the animal gaze in Animals in film, arguing that ‘the exchange of the look is, in the absence of the possibility of language, the basis of a social contract.’ [4] and so with Mick and the water buffalo, unable to communicate through words, they share a non-verbal connection through eye contact and appear to successfully understand each other; the water buffalo does as Mick wishes and ceases to be a threat. Burt also says of the gaze, ‘communication by the look… can be seen to be more primal and perhaps also telepathic’ [5] which we can apply to Crocodile Dundee as being a moment of mutuality between Mick and the buffalo. Their wordless understanding codes Mick as belonging to the outback and his ability to communicate with animals on a higher level demonstrates their shared primal instincts. He is part of this world, and it respects him. This further inscribes his status as a domineering man with control over the wilderness of the Australian bush and distances him from the refined, misplaced Sue.

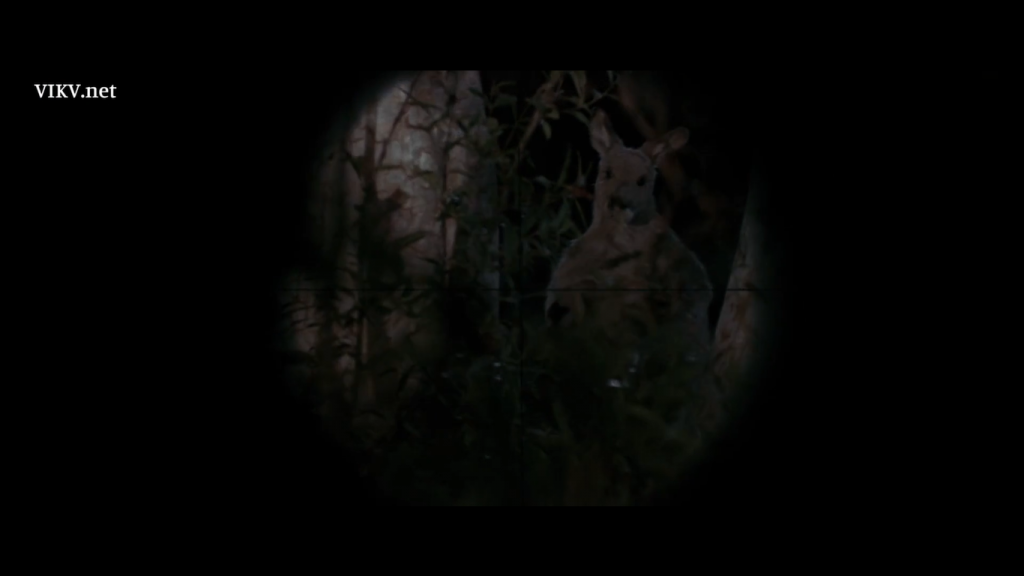

The animals of the film also become tools to further romantic interactions within the narrative, thereby reinforcing stereotypical gender roles. At 31:24, Sue mistakenly bathes in a crocodile inhabited pool and is attacked. She is inherently sexualised, (fig. 4) placed in a revealing bathing suit, and is watched through the bushes in animalistic voyeurism by Mick, shown through a POV shot, once again aligning her naivety in the bush as being tied to her status as a domestic woman. The crocodile attack acts as a character-defining moment for Mick to show off his heroic prowess and swoop in to save Sue, spotlighting how out of place she is.

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

There are several shot-reverse-shots of Sue’s terrified expression on the left and the jaws of the crocodile clutching her water bottle on the right (figs 5 & 6); the human fear and animal danger mirror each other, visually encompassing themes of wildness vs. domesticity. Once again, Burt’s animal gaze appears, as the two grapple and are forced to look into each other’s faces. However, the feminine ‘damsel in distress’ cannot communicate or exert power over the crocodile from a point of mutual understanding, unlike the hyper-masculine Mick, and so she must struggle until he arrives to save her. Because Sue is our heroine, we celebrate the death of the crocodile as the defeat of a threat and view Mick in a positive light for exercising his control over the bush, as following the conventions of the action-adventure genre. It is an opportunity to glorify Mick as a protective, attractive figure and elevates his masculinity, instilling his power over animals as being indicative of his empowered male identity. Sue flinches as the animal is slaughtered, coding her as far more sympathetic to the crocodile, seeing its death as her mistake rather than a necessary defense. Rose Lucas discusses gender politics that play into Mick and Sue’s reactions to the animal world, suggesting that Mick’s rampant masculinity is associated with ‘rationality, transcendence, activity, taming and colonisation’ [6], hence his role as a combater of the bush and protector of the ‘clueless’ female. This plays in opposition to the ‘feminized attributes of emotion, corporeality, passivity’ [7] that Sue possesses, wherein her sympathy and emotional responses to the outback render her both more sensitive to her surroundings but ultimately at its mercy and in need of a dominating figure to protect her.

When his status as a desirable male in the eyes of Sue becomes threatened by her empathy with the creatures, Mick moves further into the realm of animalism by defending a group of kangaroos. At 24:00, Mick and Sue come across poachers who are shooting at the animals, and Sue is horrified by the body of a kangaroo at their feet. Initially, he claims ‘Well, there’s no law against that.’, refusing to get involved. When Sue stares him down and essentially emasculates him, he runs to their aid, utilising the body of the fallen kangaroo as a front (fig. 7). Mick becomes the kangaroo, using it as a mask to and shoots back and reaffirming Sue’s affections for him. This incident further asserts the idea that much of Mick’s affinity with the animal world is based on his identity as a strong, Australian male. When his masculinity is questioned by a desirable female, Mick embraces animality physically, taking on the corporeal form of the kangaroo and turning against humans, in order to reconfirm it.

Animals are symbolically used throughout Crocodile Dundee to drive both human characterisations and human relationships. It is the crocodile in the role of predator that allows for the blossoming romance of Sue and Mick to begin and it, along with the water buffalo, are both used by Faiman to communicate Mick’s conspicuous masculinity and rugged, boisterous personality. The haunting presence of a crocodile through Mick means the audience is constantly reminded of the physical capabilities of the hero and the defeat of animals – both violent and nonviolent – becomes totemistic of desirable virility. The film argues that remaining true to wildness means you will be successful, not only in yourself, but in all societal contexts. Mick triumphs over Australia and New York, achieving the conventional heterosexual romance and public adoration by his refusal to abandon his barbarity.

In the closing of the film, Mick and Sue are reunited in the ritual coupling attained through animalism. ‘We’re jammed in like sheep’, a subway user tells him referring to New Yorkers as seemingly domesticated animals; Mick uses this analogy to combat the urbane world; he walks atop the subway users as if they were a flock of sheep and he was a sheepdog, once again aligning him as thinking ‘like an animal’ and using his domination of animals to be successfully masculine, and he falls into the arms of the desirable woman Sue (figs. 8, 9 & 10).

Fig. 8 An Australian sheepdog walking over sheep

Fig. 9 Mick walks over the subway users

Fig. 10 Mick and Sue are reunited

The key message of the film seeks to encourage the audience to never sacrifice their values of true self despite being incongruent to one’s surroundings – as Mick remains true, he ends the film as the ultimate hero. Faiman reaffirms the myth of the virile Australian bushman. Conservative gender roles are through the charismatic action man and the threatened damsel; however ‘wild’ the narrative encourages you to be, it does not stray away from the domestically acceptable heterosexual romance. It is a strangely paradoxical message, asking you to never fully sacrifice yourself to the ‘sheep’ mindset of corporate American society, but to always adhere enough to societal rules to ensure you receive a conservative, conventional prize of an attractive partner.

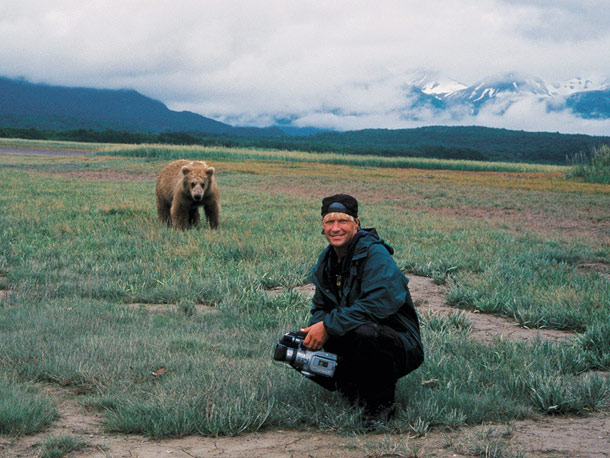

Mick Dundee appears to be a fictional predecessor to Steve Irwin, another beloved ‘real Aussie larrikin’ [8] whose fascination with the animal world sadly led to his early demise in 2006. Similarly, the figure of the tragic, and perhaps overzealous animal obsessive is mirrored in Timothy Treadwell, star of Grizzly Man [8], who was mauled by the bears he desperately sought to connect with in 2003. Mick’s mythic presence is what saves him from an early death – his status as a fictional Hollywood hero allows him to be a larrikin without tragedy – he is beyond death.

Animals ultimately serve to reinforce masculinity as totems used to define identity and create opportunities to drive heterosexual romance, taking on the role of a ‘threat’ for a hero to defend against, signifying attractive masculinity which translates to victorious, mythic and elevated heroism.

References

[1] Rose Lucas, (1998) ‘Dragging it out: Tales of Masculinity in Australian cinema, from Crocodile Dundee to Priscilla, queen of the desert’, Journal of Australian Studies, 22:56, 138-146 p.141 <https://www-tandfonline-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/doi/abs/10.1080/14443059809387368>

[2] Entry for ‘Larrikin’, Cambridge Dictionary Online, <https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/larrikin >

[3] Anouk Lang, (2010) ‘Troping the Masculine: Australian Animals, the Nation, and the Popular Imagination, Antipodes, 24:1, Brooklyn: Wayne State University Press 5-10 p. 6

[4] Jonathan Burt, (2002) Animals in film, London: Reaktion, p. 39

[5] Burt, p. 41

[6] Lucas, p139

[7] Lucas, p. 319

[8] The Guardian, ‘’Crocodile hunter’ Steve Irwin killed by a stingray’, 4th September 2006, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/sep/04/australia.media> [Accessed 19/1/2021]

[9] Grizzly Man, dir. Werner Herzog, (Discovery Docs, 2005)

Bibliography

Burt, J., (2002), Animals in film, Chapter 1, ‘Film and the History of the Visual Animal’, London: Reaktion, 17-83

Cambridge Dictionary Online, ‘Larrikin’, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/larrikin [Accessed 19/1/2021]

The Guardian, ‘’Crocodile hunter’ Steve Irwin killed by a stingray’, 4th September 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/sep/04/australia.media [Accessed 19/1/2021]

Lang, A., (2010), ‘ ‘Troping the Masculine: Australian Animals, the Nation, and the Popular Imagination’, Antipodes, 24:1, Brooklyn: Wayne State University Press 5-10

Lucas, R., (1998), ‘Dragging it out: Tales of masculinity in Australian cinema, from Crocodile Dundee to Priscilla,queen of the desert’, Journal of Australian Studies, 22:56, 138-146

Media

Crocodile Dundee, dir. Peter Faiman, (Rimfire Films: 1986)

Grizzly Man, dir. Werner Herzog, (Discovery Doc: 2005)

Further Reading

Bellanta, M., (2012), Larrikins: A History, Brisbane: University of Queensland Press

Greer, G., ‘That sort of self-delusion is what it takes to be a real Aussie larrikin’, 5th of September 2006, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/sep/05/australia

Raynor, J., (2017), Contemporary Australian Cinema: an introduction, Chapter 4, ‘The Male Ensemble Film’, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 94-128

Grizzly Man, dir. Werner Herzog, (Discovery Doc: 2005)

The Crocodile Hunter, creators John Stainton and Steve Irwin, (Animal Planet: 1997 – 2004)