“I’ll be your family.”

Jonas Cuaron’s 2023 Chupa is a heartwarming tale of two isolated characters who form a unique bond in pressured circumstances. Alex, grieving from his father’s recent passing, goes to stay with his extended family in Mexico and connects with a misunderstood chupacabra, who is separated from his family as a result of hunters. Together, they embark on a journey to reunite Chupa with his family. Set in the outskirts of San Javier, Alex protects him from the hunters – with help from Grandad Chava’s mountain lion championing wrestling skills (he really did scare off a lion). It is a film that entertains children in its fun and playful depictions of Chupa’s bond with the children, while showcasing the importance of family and its loyalty and protection. Through the bond between Alex and Chupa, Cuaron underlines the film with the theme of grief and subtly portrays how his bond with Chupa inspirits Alex’s healing journey. Heartwarming? Undoubtedly. Grab your popcorn.

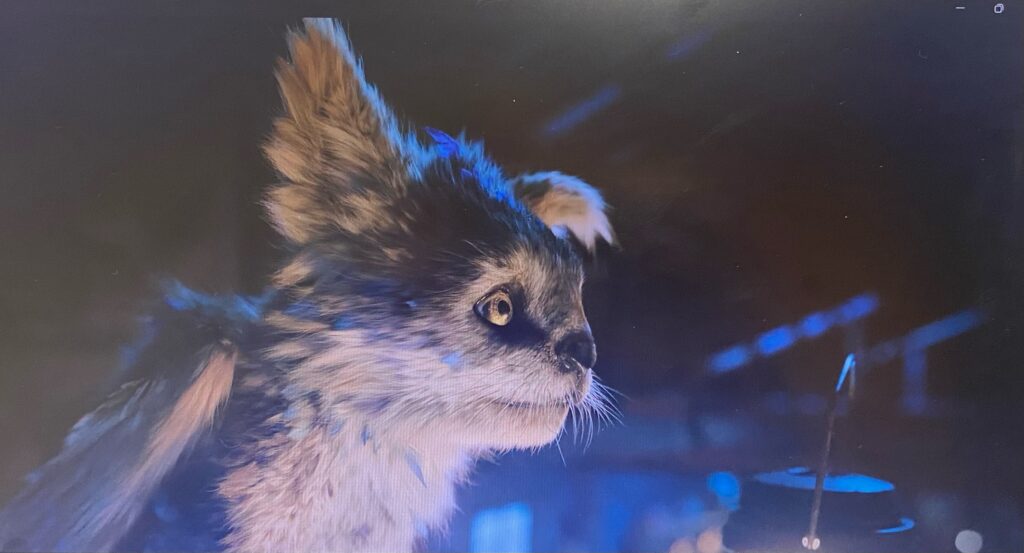

As a fantasy adventure film, director Cuaron redefines the common beliefs surrounding the fantastical chupacabra. The myth of Chupacabras presents them as monstrous and dangerous goat’s blood-sucking animals.1 With their vampirish nature, you might expect to see them in a horror, rather than a family aimed film. Instead Cuaron aimed “to create an incredibly cute creature out of a terrifying legend”.2 Any preconceived terror is banished as soon as you look at Chupa’s adorable CGI complexion. The editing and visual design of Chupa highlights the charming nature of the titular animal. The artists who designed Chupa used various reference material from birds and felines3 so he resembles common and largely domesticated animals that the viewer may care for at home. This creates an easy bond between the animal and the audience which is further emphasised by his doe eyes, cooing and soft appearance portraying an innocent and empathetic nature of appearance. As Chupa is hunted and displaced in the film by humans, there is a link to the global issue of endangered animals as a result of human interference.

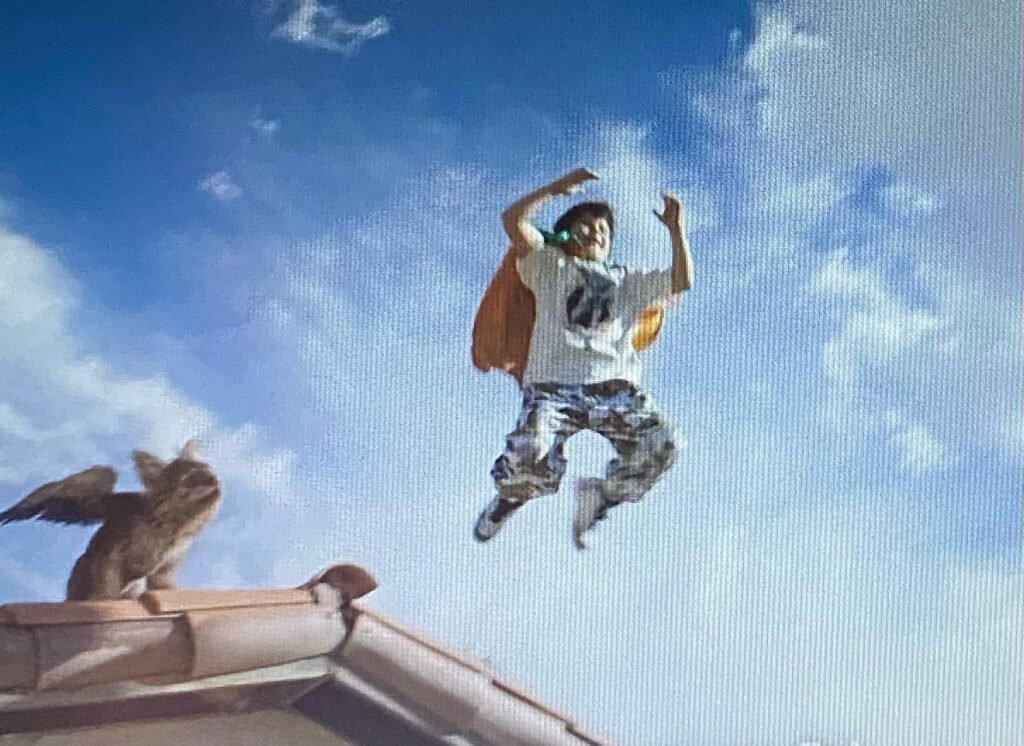

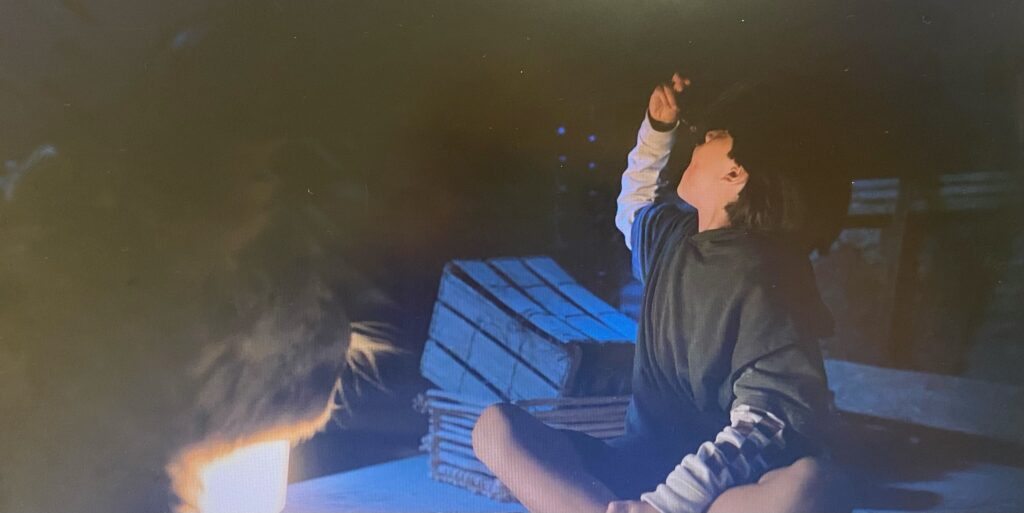

As a fresh change from the violent, nightmare-inducing animals, Chupa is portrayed as endearing, lovable and a little bit clumsy – enough to pull on any watcher’s heartstrings. Cuaron highlights the innocent nature of the chupacabra when youngest cousin Memo teaches him how to fly. The pairing of the dramatic non-diegetic music with the upwards angle in the shot of them on the roof, playfully dramatises the height of the jump into hey. Chupa is visibly nervous but Memo’s dialogue is perpetually supportive: “muy bien, you almost did it!”.4 The continuity of shots and pairing of their POV’s here evoke a fun and genuine connection and exude authenticity from both characters.

Chupa jumps when Memo expressively states that he has to learn to fly “to get away from that bad guy.”5 acting as another brief reminder of the constant threat hunters pose to animals. Chupa bounces to the end of the roof and makes the jump, the camera follows the leap and Chupa’s wobbling and frantic attempt to flap with wings. As Chupa abruptly falls out the sky, the camera stops following him for a short second so he nearly falls out of shot. It then also quickly drops down to be level with Memo and Chupa in the hey for comical effect. This exaggerates the abrupt ending to Chupa’s attempt to fly and induces the light hearted nature of the scene. The supportive and trusting atmosphere in this scene exaggerates the innocence of the animal who needs the support and care from humans.

Throughout the film, the hunters are portrayed as the antagonists of the film, which contrasted to the innocent depiction of Chupa, ignites anger towards animal hunters and invokes a heightened level of horror in the hunters’ intentions. The director cleverly utilises the image of Chupa’s domesticated appearance to act as a metaphor for animal rights by employing the idea of harming animals, resonating with viewers particularly those with pets or a love for animals. The idea that people deeply value their bonds with companion animals, yet routinely devalue others, considering them as commodities to satisfy humans,6 illustrates a sense of hypocrisy, emphasising the need for universal care. This encourages the audience to make an impact on saving endangered animals, and fight against harming them and displacing them.

A theory behind chupacabras is that they were actually mistaken for Tasmanian tigers; the previous alleged sightings were of the extinct marsupial.7 The fact that the species is now extinct due to human destruction alludes to the critical issue of endangered species. Furthermore, Cuaron’s alteration of the perception of Chupa incites a motivating undercurrent to the film against animal endangerment. This scene particularly, and the film as a whole, emphasises Chupa’s innocence and youth instead of a hunting animal. Chupa’s alteration in appearance and demeanour therefore is ironically flipped to draw attention to the fact that humans are also hunters. As Chupa is a mythical animal, something you cannot see in real life, the CGI creature retains a magical quality which is further enhanced by the strangeness in his appearance. This adds to Chupa’s innocent demeanour and highlights the selfishness behind his intentions and lack of care for animal welfare and ignorance to the potential extinction as a result of his actions.

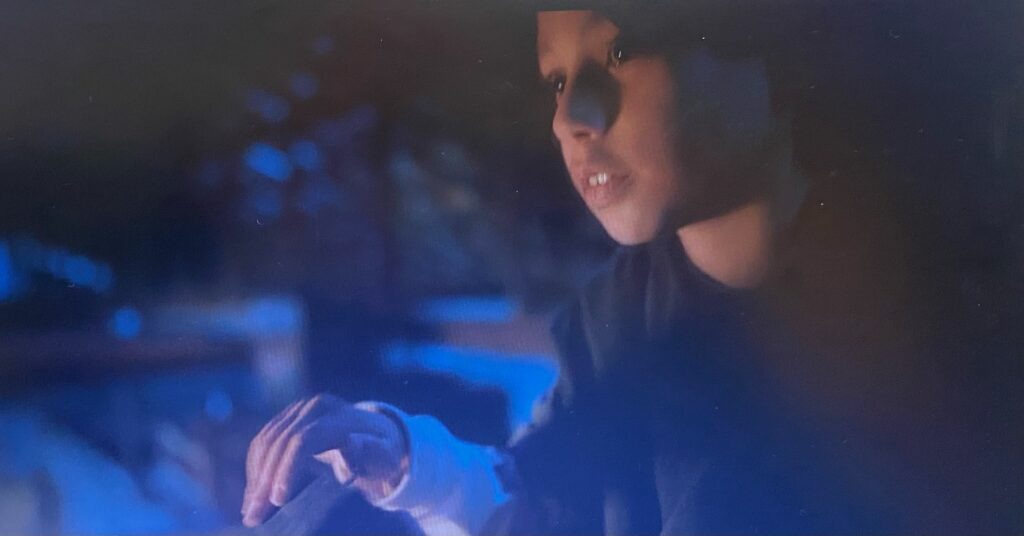

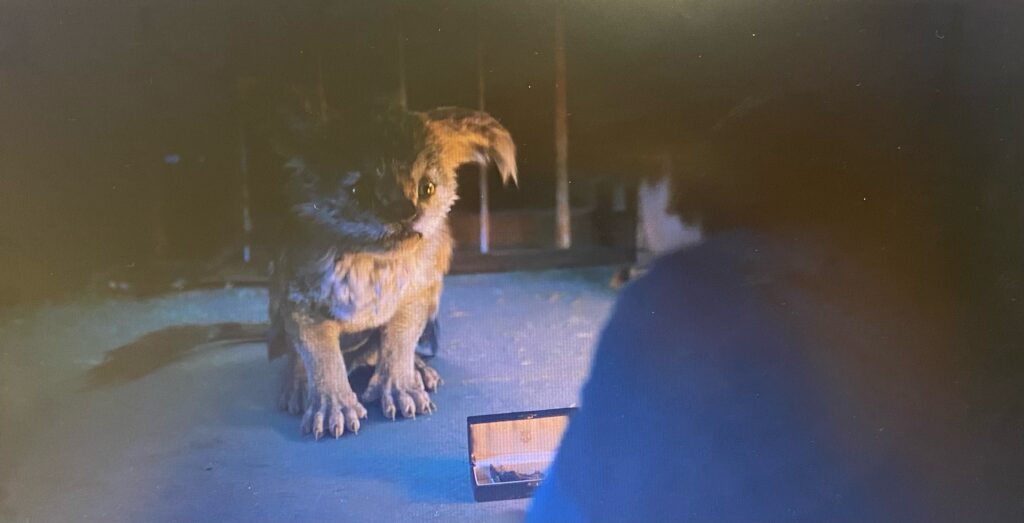

The central human-animal bond speaks to the true nature of friendship and finding in each other what they need. As two misunderstood and isolated characters, their solidarity connects them as they are both in similar situations; displaced and separated from family. In their first proper meeting, they are away from the house in the barn loft which emphasises their isolation. This is also the audience’s first proper meeting of Chupa and by meeting him through Alex, it encourages the audience to reflect on his lonely emotional state as they meet. Cuarón uses mise-en-scene to make the scene feel homely and intimate. It is late at night and dimly lit by a lantern, creating intimacy in the actors’ placement around the lantern to see each other clearly. It further nods to their isolation as it dims the rest of the shot except themselves who are lit up by the light. This connotes the idea that they are isolated yet connected in their loneliness. This also focuses the audience on their facial expressions and stance which are visibly relaxed and comfortable in each other’s company.

Cinematographer Nico Aguilar uses mirrored POV angles to display their exchange. The camera slowly cuts between their POV’s to display the tenderness in their developing connection. The low camera angle as Alex is sat on the floor to be at Chupa’s level further heightens the connection between them, whilst also aligning the viewer with them to engage us closely in their interaction. Their bond is so pure it transcends any animal-human communication barriers. The fact they can only communicate through actions further shows their rapport.

Alex gives Chupa some chorizo and in return he offers Alex a pre-captured mouse. This exchange of gifts symbolises the reciprocal nature of their companionship; Alex protects Chupa and helps him reunite with his family, Chupa acts as a starting point for his healing. Alex initially is unable to process the grief and share his feelings with his family, but he is able to be vulnerable with Chupa, the first step to acknowledging and allowing the feeling of grief. This brings awareness to an animal’s ability to help individuals feel less alone in their grief by providing a source of comfort and companionship.8 By analysing the central human-animal relationship, it reveals new layers to the film’s simple plot. The emotional depth of grief is not explicitly shown, but in Alex’s immediate trust and care as a direct contrast to his reserved nature in all his other relationships, the audience realises how much he appreciates Chupa’s companionship.

The final scene of the film is an uplifting ending that reinforces the symbiotic relationship of humans and animals, shown to have many positive impacts. As Alex boards the aeroplane to leave San Javier, he says an emotional farewell to Chava. In contrast to his shy and reserved greeting at the beginning of the film, he expresses clearly how much he will miss him while giving him a hug. This demonstrates an improvement in his ability to express himself and be vulnerable with others, following his time with Chupa. The use of human actors with CGI animals makes the natural human emotions more compelling. Alex’s journey in addressing the grief of his father’s passing is further symbolised through him holding his father’s old luchador mask given to him by Chava. While he has helped Chupa reunite with his family, he has also opened up to his father’s side of the family as they bonded over luchador and protecting Chupa from the hunters. Alex looks out the window to see Chupa flying alongside the plane. This is representative of how far Chupa has come since his flying lessons with Memo and shows the impact of human help. The camera slowly zooms in on Chupa from Alex’s POV and gradually zooms out on Alex in the aeroplane from Chupa’s POV. This conveys their close bond despite their separation and distance between them. The speed of the camera movement is slow, to give them a moment for goodbye. In Chupa’s reappearance, the audience recognises his growth in acceptance of grief as he realises Chupa will always be with him. This is symbolic of his father, who remains with him in memory.

The final tracking shot follows Chupa as he rejoins his family flying over the rocky landscapes of Mexico. They feel congruent with this setting, as they are free in their natural habitat, not in the hands of the hunters who have left them as an endangered species. Cuaron pairs this final image with a triumphant soundtrack to emphasise Chupa’s freedom, which is further mirrored in his final shot in flight. The use of a tracking shot immerses the audience in a moment of rejoice. As Chupa soars towards and over the camera, the shot cuts and he is allowed freedom without any human interference. This short sequence is representative of the central symbiotic relationship and leaves the audience uplifted with Alex succeeding in reuniting Chupa with his family combined with Alex’s healing.

To conclude, Chupa at its heart is a story of an unlikely companionship that saves the other. Cuaron uses Chupa to be a friend to Alex at his moment of need and show the inspiring effects of his presence to demonstrate the brilliance of animals. Chupa acts as a catalyst for Alex’s personal growth showing the human-animal relationship is equally balanced in the way they both help each other. Their bond is a vitally significant part of the film and through a deeper analysis of this, it reveals layers to what is fundamentally a simple family film. The film utilises human-animal relations to acknowledge and criticise the grave nature of animal endangerment. Chupa’s storyline is similar to that of Paddington. In his unavoidably lovable clumsiness, both of these creatures are often seen as scarier than they are portrayed in their respective films. Both animals are adopted and protected by eccentric families who value loyalty first and foremost. Importantly, bears are also endangered. Therefore, in looking closely at films like Paddington and Chupa, it can bring awareness to, and begin discussions of, endangered animals.

Footnotes

- Lewis, R. Chupacabra. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/chupacabra. [Accessed 14th January 2024].

Lewis, R. Chupacabra. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/chupacabra. [Accessed 14th January 2024]. ↩︎ - Dilill, J. Everything You Need To Know About Chupa. (2023). What Is ‘Chupa’ About? New Jonás Cuarón Movie Release Date – Netflix Tudum [Accessed: 7th January 2024] ↩︎

- Chupa. MPC Film. (2023). https://www.mpcfilm.com/en/filmography/chupa/ [Accessed: 10th January 2024] ↩︎

- Chupa. dir, by, Jonas Cuaron, (26th Street Pictures, 2023) ↩︎

- Chupa. dir, by, Jonas Cuaron, (26th Street Pictures, 2023) ↩︎

- Dhont, K., Hodson, G., Loughnan, S., & Amiot, C. E. (2019). Rethinking Human-Animal Relations: The Critical Role of Social Psychology. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(6), 769-784 https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430219864455 [12th January 2024] ↩︎

- Logan, D. Exemplore. (2023). According to This Theory, It’s Possible that Chupacabra Sightings Are Actually the Supposedly Extinct Thylacine – Exemplore News [Accessed: 10th January] ↩︎

- Andrus, B. Grief and Support Animals: The Comforting Presence of Pets. (n.d). Grief and Support Animals: The Comforting Presence of Pets (myfarewelling.com) [Accessed: 12th January 2024] ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Chupa. dir, by, Jonas Cuaron, (26th Street Pictures, 2023)

Secondary sources

- Andrus, Becky. Grief and Support Animals: The Comforting Presence of Pets. (n.d). Grief and Support Animals: The Comforting Presence of Pets (myfarewelling.com) [Accessed: 12th January 2024].

- Chupa. MPC Film. (2023). https://www.mpcfilm.com/en/filmography/chupa/ [Accessed: 10th January 2024].

- Dilill, John. Everything You Need To Know About Chupa. (2023). What Is ‘Chupa’ About? New Jonás Cuarón Movie Release Date – Netflix Tudum [Accessed: 7th January 2024].

- Dhont, Kristof., Hodson, Gordon., Loughnan, Steve., & Amiot, Catherine. E. (2019). Rethinking Human-Animal Relations: The Critical Role of Social Psychology. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(6), 769-784 https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430219864455 [12th January 2024].

- Lewis, Robert. Chupacabra. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/chupacabra. [Accessed 14th January 2024].

- Logan, Diana. Exemplore. (2023). According to This Theory, It’s Possible that Chupacabra Sightings Are Actually the Supposedly Extinct Thylacine – Exemplore News [Accessed: 10th January].

Further reading

- Martinez, Kiko. Interview: Director Jonás Cuarón Talks Netflix’s ‘Chupa’ & the Real Animal Used for Filming. (2023). INTERVIEW: Director Jonás Cuarón Talks Netflix’s ‘Chupa’ & the Real Animal Used for Filming (remezcla.com) [Accessed: 7th January 2024].

- Fair, James. Mongabay News & Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline. (2021). Study suggests the Tasmanian tiger survived into the 21st century (mongabay.com) [Accessed: 10th January 2024].