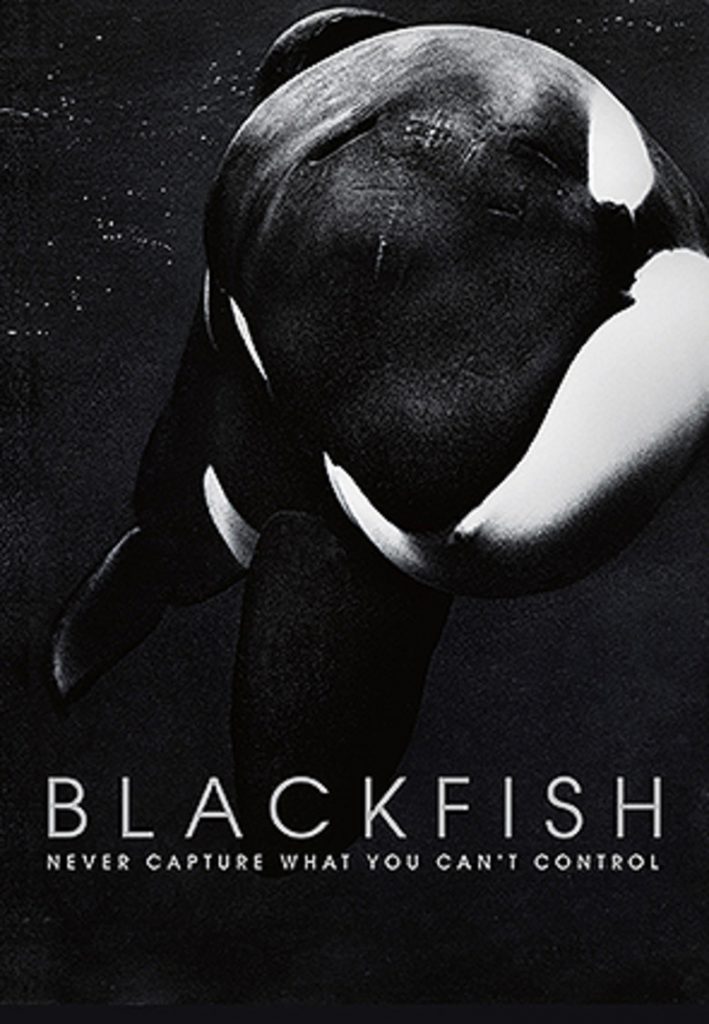

Blackfish is a documentary which focuses on the danger of keeping killer whales in captivity. The documentary film argues that this danger affects, not just the human trainers of these highly intelligent animals, but also the marine creatures themselves. Director Gabriela Cowperthwaite focuses on one whale in particular; Tilikum a 6 ton bull orca, who was captured at a young age and trained by humans. The film uses the history of this single whale, and its implication in the deaths of three people, to form an investigation into the difference between the public image of the marine park, Sea World, and the actuality behind the scenes. Cowperthwaite argues against taking these animals out of their natural environment, as keeping them in captivity can only lead to tragedy.

The film relies heavily on the key stylistic features of the documentary genre. The creative choice to exclude a narrative voiceover suggests that Cowperthwaite is allowing the viewers of Blackfish to reach their own conclusion. However, we must bear in mind that the actuality that is being presented has been edited and manipulated through aesthetic cinematic means. Cowperthwaite’s aesthetic decisions inevitably influence the audience’s perception of the actuality represented in the film, therefore the judgement that the viewer reaches has been shaped and manipulated through the representation of facts. The film incorporates interviews showing the ‘rueful voices of former trainers and whale experts’, which creates ‘a narrative driven by disillusion and regret.’ [1] These interviews with former trainers and scientific professionals act as the narrative voiceover of the film to introduce the argument and to consequently, move it along. Cowperthwaite manipulates the idea of an interview voiceover as she occasionally employs the use of contrasting opinions. Significantly, throughout the film there is a lack of an argument defending Sea World’s actions. The interviews presented in Blackfish articulate the horrors of keeping orcas in captivity, as former trainers recall the tragedy of the lives led by these captive marine creatures. However, the concluding scenes of the film offer an argument to undermine the humanitarian approach to captive wildlife. Two contrasting views are offered as one trainer believes that keeping these intelligent highly evolved animals in captivity is atrocious, yet another trainer argues that he cannot see society valuing orcas and other marine creatures without places like Sea World.

When interviewed, Cowperthwaite mused that she hoped the film ‘has a life of its own’ and that ‘it’s a worthy tool for people that need to inform other people. It starts with us, telling them that what they’re doing is not okay.’ [2] Through the stylistic features typical of documentaries, Cowperthwaite presents a polemical documentary and offers an argument against Sea World’s captivity of orcas.

People’s fascination with the wild has led to the captivity of many forms of animals in enclosures such as zoos and marines. However, Blackfish suggests that this delight humanity has with wild creatures has now become radically fetishized. The delight has been amplified and has become part of our world of capitalism. Simply having these animals purely on display for the human eye does not satisfy the capitalist delighters’ world, but the animals have now become part of a spectacle in a multi-billion dollar industry. In Blackfish, Cowperthwaite includes footage of past Sea World televised advertisements which portrays the killer whales as elegant creatures that can have playful and harmless interaction with the trainers. It is significant that the quality of these past advertisements contrast to the high quality imagery employed throughout the rest of the film. The advertisements seem grainy and cheap in its quality; and thus makes the viewer see them as tawdry, which ultimately portrays Sea World as a place of defunct technology. The inherent difference in the film stock alludes to the out dated values of Sea World; and argues that they should reassess their moral principles. One particular advert from 1990 depicts a film of one of the female orcas giving birth, whilst the voiceover of the advert narrates that she ‘gave the performance of a lifetime.’ It is significant that the television advertisement of these performing killer whales alludes to the performative nature of their entire existence in captivity. Giving birth, the most natural thing there is, has now been twisted into a performance by the multi-billion industry of performing marine creatures.

Cowperthwaite offers cinematic juxtaposition in the opposition between the Sea World advertisements and the ‘realist’ footage of the orcas in the wild. The beauty of the killer whales portrayed in the advert, and other recordings of the trainers performing with the orcas are accompanied by swelling orchestra music; which at first glance seems to enhance the amazing nature of the human and animal interaction. However, when it is compared to the music that backgrounds the killer whales swimming in the wild ocean; the advertisement music, at second glance seems loud, heavily orchestrated and farce-like.

The aesthetic choice of including footage depicting killer whales in the wild followed by a clip of an orca being heavy-handedly transported using huge man-made machines further emphasises the cinematic craftsmanship Cowperthwaite undertakes in shaping the audience’s perception of Sea World’s treatment of the orcas. In an interview with Dave Duffus, an OSHA expert witness and whale researcher, he states that the orcas are ‘great spiritual beings’, and the music and the mise en scène of the killer whales peacefully swimming in the ocean against a backdrop of majestic cliffs seems to mirror that opinion. In contrast, the next scene begins with a blackout with only the sound of whirring mechanism. The footage then reveals Tilikum being transported with the use of great machines. The juxtaposition of these two clips, in both the visual and audio, foreshadows the destructive and unnatural outcome of humanity attempting to integrate our lives with natural wildlife.

Furthermore, the portrayal of Sea World’s representation of the killer whales is undermined by the scientific knowledge that is incorporated into the film through interviews with a neuroscientist. The interviews allow for professional knowledge to be articulated, and consequently Cowperthwaite is able to establish an argument which scientific knowledge supports. The audience’s trust in the accuracy of the facts presented in the interviews allows for Sea World’s misdemeanours to be revealed. Interestingly, Cowperthwaite employs the use of interviews to link scientific, spiritual and empathic interpretations. The film offers several kinds of expertise views in an attempt to offer the audience a full representation of facts. The inclusion of an interview with the harrowed Spanish girlfriend, whose fiancé died in a tragic accident involving an orca, alludes to the universal problem of marine captivity.

Additionally, interviews with former trainers reveal that in the past, Sea World separated baby orcas from their mothers due to them disrupting performances. Clips of orcas wailing are voiced over the interview, which offers an audio re-enactment and the harrowing separation, allowing for the viewers to sympathise and be emotionally moved. It is significant that Cowperthwaite includes the story of the separation after the interview with Lori Marino, a neuroscientist who offers a scientific theory suggesting that orcas have a part of the brain, which other mammals including humans, do not possess. This part of the brain exemplifies the feeling of self, community and therefore family. With this added knowledge, Sea World’s separation of the family unit becomes additionally harrowing and cruel. Although the film grants the scientist with expertise authority, as a viewer we are encouraged to remain vigilant and to question the reliability and accuracy of such scientific theories.

Emotional manipulation is further demonstrated through the interview with John Crowe, one of the fishermen who hunted the baby orcas for Sea Land. The interview includes genuine footage of these baby whales wailing for their mothers, and the communication received back and forth from the separated family unit. The combination of the harrowing confession of Crowe, the footage of the separation and the audio accompaniment of the mothers howling allows for the viewers to be emotionally influenced by the film’s polemical nature. Although Crowe is presented as being morally dubious, the portrayal of him as being psychologically tormented by his involvement with Sea Land encourages the viewers to not question his lack of action towards the safety and well-being of the orcas.

Furthermore, the film incorporates various footages of the violent incidents involving the killer whales and their trainers. These shocking clips consist of the viewer having to watch people get seriously hurt by the orcas. From getting crushed by a killer whale to having an arm bent into a U-shape; this footage allows the audience to comprehend the danger that the animals present in human-animal interaction. Additionally, keeping them in captivity is revealed as being dangerous to the orcas themselves. Tilikum, from a young age, is shown to have been endlessly raked (with other whales’ teeth) in an act of dominance from the female orcas. The audience is shown filmic clips where Tilikum is visibly bleeding during performances. These disturbing images combined with narrative interviews which articulate the psychological effect of keeping orcas in captivity allow for the audience to shift the judgement of blame away from the animal, and onto the people who are meant to be responsible for them.

Cowperthwaite’s artistic decision allows the interviews to compose an argument. Ultimately, the various depictions of orcas lead to one outcome; it provokes feelings of sympathy and pathos. The representations of Tilikum as a playful intelligent animal, yet also a dangerous, destructive and aggressive animal, combined with the scientific knowledge, allows for the audience to shift the blame of animal aggression away from the animal itself to the people responsible for him. Although the aesthetic choices, such as the lack of a voice over, suggests the audiences’ active participation in reaching their own conclusion, the form of the cultural text ultimately shapes how the audience reacts as the documentary does not strive for complete fairness and objectivity, but offers a polemic message. Erik Barnouw comments on directors’ ‘compelling need to document some phenomenon or action’ [3]. Although Cowperthwaite does document the tragedy of captive orcas, the word ‘document’ suggests the passive role of the film. Blackfish is not merely a documentary intended to inform and portray a certain event; it portrays captivity in a certain manner to argue against it, and thus is becomes a polemic documentary.

In 2005, director Werner Herzog released the documentary film, Grizzly Man, which chronicled the life and death of a bear enthusiast and activist, Timothy Treadwell. When compared, it is easy to see the similarities between Blackfish and Grizzly Man. Both films engage in the argument of whether humanity can interact with the wild without it ending in destruction and tragedy. Herzog argues that humanity cannot interact with the wild without tragedy, and uses the story of Treadwell and his death to illustrate this. Herzog argues that the ultimate tragedy of Grizzly Man is human involvement. Similarly, Cowperthwaite also engages in a contemporary cultural argument to demonstrate the danger of the captivity of marine creatures. Both films discuss the danger of humans involving their lives with wildlife; the films articulate the unfairness of the unethical cruel treatment of animals, and ultimately question the human-animal interaction valued by contemporary society.

Further Reading References

IMDB link for the film: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2545118/

Trailer for the film:

Interview with Gabriela Cowperthwaite explaining why she chose to make the film:

Elizabeth Batt on the public reaction to Blackfish, Op-Ed: Bombed by Blackfish, fallout continues for SeaWorld, The Digital Journal, 31st October 2013 https://digitaljournal.com/article/361261

Lori Marino, the neuroscientist interviewed in Blackfish investigates the psychology of marine animals:

Lori Marino, Humans, Dolphins and Moral Inclusivity, Edited by R. Corbey and A. Lanjouw, The Politics of Species, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2013) pp. 95-105.

Werner Herzog, Grizzly Man, Lions Gate Films, 2005.

Louie Psihoyos, The Cove, Lionsgate, 2009.

Bibliography

Barnouw, Erik, Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983).

Catsoulis, Jeanette, ‘Do Six-Ton Captives Dream of Freedom?’, The New York Times, 18th July 2013 https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/19/movies/blackfish-a-documentary-looks-critically-at-seaworld.html?_r=0 [accessed 12th November 2013].

Chris, Cynthia, Watching Wildlife (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

Cowperthwaite, Gabriela, Blackfish, Magnolia Pictures, 2013.

Cowperthwaite, Gabriela, ‘’Blackfish’: The Documentary That Exposes SeaWorld’, SeaWorldofHurt, 15th July 2013 https://www.seaworldofhurt.com/blackfish.aspx [accessed 14th November 2013].

Warren, Charles, Beyond Document: Essays on Nonfiction Film (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1996).

Winston, Brian, Claiming the Real 2 (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

[1] Jeanette Catsoulis, ‘Do Six-Ton Captives Dream of Freedom?’, The New York Times, 18th July 2013 https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/19/movies/blackfish-a-documentary-looks-critically-at-seaworld.html?_r=0 [accessed 12th November 2013].

[2] Gabriela Cowperthwaite, ‘’Blackfish’: The Documentary That Exposes SeaWorld’, SeaWorldofHurt, 15th July 2013 https://www.seaworldofhurt.com/blackfish.aspx [accessed 14th November 2013].

[3] Erik Barnouw, Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 3.