“Wolf! Alright, I’ve decided to be your apprentice and learn to be strong! (…) I’m sick of being a sheep, all we ever do is stand in corners and shake!”

– Chirin from Ringing Bell

Ringing Bell was originally released in Japanese – this article focuses on the English dub.

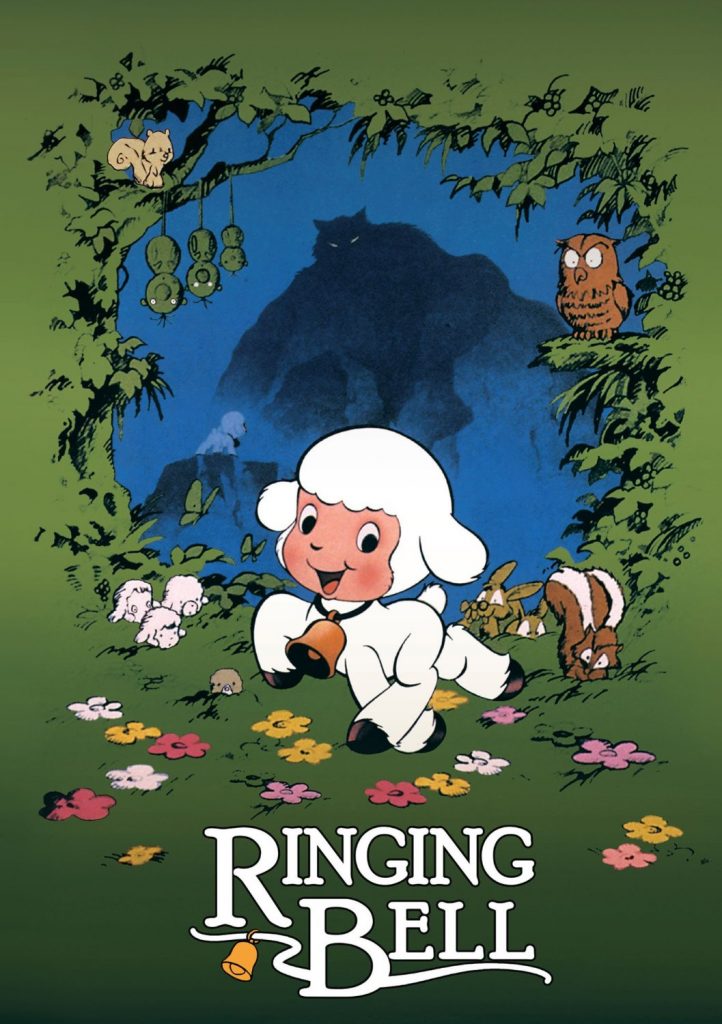

Sanrio, the Japanese entertainment company behind the titan of character merchandising Hello Kitty, produced films for a brief period, from 1977 to 1985. Ringing Bell, the fifth film the label released, is an adaptation of Takashi Yanase’s storybook of the same name and directed by Masami Hata, released as a double-feature in Japan alongside The Mouse and His Child before hitting American television screens in the early 1980’s. The focus of Sanrio’s brand on all things cute complimented Yanase’s success in merchandising one of his cartoons from an earlier storybook aimed at children: Anpanman, a superhero with a sweet roll for a head. Visually, Ringing Bell’s Chirin initially evokes this aesthetic with his floppy ears and frolicking hooves; as Paul Wells points out in his essay on animated literary adaptations, an assumed relationship exists between children’s storybooks and animation because of their shared visual format [1]. During the production process Yanase’s design for Chirin was simplified in accordance with Sanrio’s characteristic style, shrinking his body and smoothing his wool to make him cuter still, but the film’s sudden darkness of tone detracts from Sanrio’s previous animations and the creative direction of its character culture.

As a young lamb, Chirin lives on a farm in a lush meadow amongst other sheep. Because of his carefree, scatterbrained nature he is fitted with a bell to allow his mother to find him when he wanders from her. She warns him against straying past the fence, for that is where the Wolf King lurks and, as expected, his ‘favourite food is baby lambs’. However, when the Wolf King comes down from the mountain and kills Chirin’s mother, Chirin pursues him and demands the Wolf King teach him to ‘become a wolf’, thus beginning an uneasy mentor-student relationship grounded in the prey-predator dynamic. This is further individualised by the traumatic circumstances of this apprenticeship, one that comes to a fatal conclusion when Chirin, now a ram, gores the Wolf King to death after he is unable to bring himself to stage an attack on the flock he was born into. Rejected by his former family, Chirin returns to the mountain and laments the Wolf King’s death, caused because he ‘wasn’t able to become a wolf’. The narrative voiceover employed frequently throughout the film explains that Chirin disappears, forgotten about, although the ringing of his bell is heard during a terrible blizzard.

“But the wolf still came, and the sheep still died. Helpless at the fangs of their enemy, nature had been unfair to Chirin…and to his mother.”

– The Narrator from Ringing Bell

Judged on the aesthetic approach of its promotional material, Ringing Bell’s genre appears unambiguous: an anime adventure-drama aimed at children. Upon watching, however, both the thematic direction and the filmmaking decisions involved in its creation reflect elements of additional genres, designed to sensitise the exaggerated cartoon style of Ringing Bell. The score begins with an acoustic melody that serves as a leitmotif, introducing and ending the film, but soon becomes orchestral and reminiscent of the drama Western, filled with the heroic sounds of brass and percussive instruments. Much of it includes lyrics that narrate the events of Chirin’s life as they unfold on screen which, alongside the commentary made by a non-diegetic storyteller, draws attention to the fact that, as David Bordwell explains, these storytelling techniques are part of ‘a long-standing convention (…) whereby every tale has a teller and receiver’ [2]. As Chirin dedicates himself to living a ‘wolf’s life’; demonstrated through frozen shots of him fighting predators, but never engaging in predation himself; the mode of sonic storytelling changes with him, transforming in tonic note and turning wrathful.

Indeed, the film seems to speak directly to its audience of children, and its messaging is uncomfortable: mother doesn’t know best, because the wolf can get you anyways. This notion echoes Disney’s Bambi, released nearly three decades earlier, in 1942, but Ringing Bell takes the warning further: sometimes, you can become the wolf too.

Or can you? Significant to Ringing Bell’s engagement with the prey-predator dynamic is the representation of the Wolf King as having an increased awareness of his drive to predate, in contrast to Chirin who rejects a ‘sheep’s life’, which, the film explains, might as well be synonymous with a ‘wolf’s dinner.’ Importantly, however, is the film’s explicitness in referring specifically to the ecology of the wolf and a sheep, a perception already established in the mind of the child through children’s literature that much of the animated format emerges from, such as in the case of Ringing Bell and mirrored in the instance of Bambi too [3]. Chirin is not just any prey animal. Rather, he is the weakest of them all; a lamb reliant on a barn for shelter, a human-animal relation the film does not mention, unable to conceive of his own vulnerability nor the savageness of others and, crucially, without any means of defence. A slapstick compilation demonstrates the extent of Chirin’s ignorance, each cut following the dynamic bounce of his body as it is blown, kicked, and farted out of frame, all because he tells them to ‘start running in terror.’

‘Nature’ is mentioned as the arbiter of Chirin’s fate, surrendering him, the sheep, as the analogous prey to the predatory wolf, but Ringing Bell asserts that Chirin can never become a wolf, only a predatory sheep. Indeed, he can pretend to be a wolf, but the consequences are dire. Paul Well’s writings on ‘paradigms of the naturalcultural’ examines the animated animal as meaning in flux, capable of navigating the ‘contested views of ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ [4]. Ringing Bell makes an example of this at the offset; the opening monologue that discusses the temporality of youth’s blissful evidence, using an undefined ‘we’ that, given its placement at the film’s beginning, seems to extend itself to the child viewer as a voice with knowledge to share, reflected in Chirin’s story. In doing this, Ringing Bell suggests that there is a commonality between children and baby lambs, seeking to embody a human idea about worldliness, and an animal idea about the prey-predator dynamic. This has strange consequences.

“Chirin was neither wolf nor sheep. He was an animal which caused only fear and terror.”

– The Narrator from Ringing Bell

As a ram that has divested himself of the weaknesses of the prey animal by suffering the life of a predator; an existence portrayed as solitary, competitive, and pitiless; Chirin is still, nonetheless, devoid of the carnivorous ‘need’ to eat other animals that motivates the Wolf King. This is reflected when comparing the mise-en-scène of the Wolf King on the mountain; a low shot showing him as part of the towering structure, form blended with the rock; with the film’s final scenes where a long shot shows a mourning Chirin in comparative conflict with the white palette of his environment. Chirin does not need to leave the mountain but neither is it a place he belongs. Sprung from his inability to accept the way of ‘nature’, his refusal to mature in the ‘right way’, and because Chirin cannot transform into a wolf, eating sheep, he becomes the set of ideas children view a wolf to be without being a predator.

To further frame its engagement with the heroic and the villainous in dialogue with sheep-wolf, prey-predator, relations, Ringing Bell also includes an example of a slow-motion sacrifice sequence, when Chirin’s mother becomes the Wolf King’s prey, an illustration of martyrdom popularised by the action film, and the Wolf King’s scar, a pink contrast against his black fur, jaws agape, is a recognisable shorthand for villainy across much of cinema. These conventions do not assemble to produce a Disneyfied storyline, however. Chirin, despite appearances, has ‘wolf feelings’; he understands the Wolf King when he tells him, upon accepting Chirin as an apprentice, that ‘life deals out few things besides pain.’ Ringing Bell conceives of the prey-predator dynamic around the ‘law of nature’, such that ‘in order for some to live, others must die’. Ringing Bell centres on the imagined fear this poses in the mind of the prey animal, the sheep, and, consequently, their relationship constitutes itself because of the prey-predator dynamic, not as an aberration of it. The film says that it is only natural that a sheep does not want to be eaten, and, as proven, it does not have to be. It can become predatorial itself, aided with more visual signalling, black wool and red eyes, but a sheep can never become a wolf.

Chirin makes this false equivalence when he accidentally crushes a bluebird’s nest of eggs, attempting to protect her from a snake. In seeing his own circumstances traumatically reflected back at him, between the snake and the bird, analogous to the lamb and the wolf, he is confronted by his own bodily condition and resists it. The film’s tendency to depict the Wolf King as within the film’s background, part of the black relief of the rock, makes the darkness of his ‘nature’s truth’ seem unavoidable. The Wolf King is this way because he has to be. Chirin is not, and thus he is punished for it.

Chirin’s innocence prior to the Wolf King’s attack on his mother is hyperbolic, boosted by the film’s animated format with its capacity for a certain kind of play referenced in Well’s writings. As Chirin scampers through a vibrant meadow; a bright, painted background that echoes Ringing Bell’s storybook origins; the way he flaps his legs to fly, digs a hole, and rolls into a fluffy ball around the meadow, indicate the ‘profound attention to detail that animators have paid in reproducing animal anatomy and motion’ [5], an attentiveness ‘aided and abetted by the malleability and liminal nature of animation as vehicle of expression’ [6]. In creating a coherence with this wolf-sheep ecology, it is imperative that the animator dispense with any sense of Chirin’s cartoonish whimsy, represented in excess as a lamb, when he is a ram. Prior to this, however, the development of the Wolf King and Chirin’s ecological relationship is not explored on screen at the expense of restraining Chirin’s animated stylisation. Parallel to how he behaved in the meadow, Chirin’s woe is dynamic. In his hysterics, weeping furiously, he falls from his mother’s corpse, and clambers back up it to resume his frantic crying.

In this, Ringing Bell does not necessarily shy away from the ‘long-established tradition of ‘funny’ animals in animated cartoons’ that Wells identifies, undeterred by the darkness of its theme [8]. When considered in association with Colin Odell’s book on anime, declaring it a genre that sustains character culture, the deconstruction of Chirin as an iconographic image, a figure comparable to Sanrio’s other properties, such as Hello Kitty, Gudetama, and Rillakuma, asks the viewer, child or otherwise, to find his pain comedic, yet significant [9]. His antics call attention to his animated form, but the way he is regularly positioned in frame is a reminder of his diminutiveness. The way in which his encounter with the Wolf King on the mountain is shot, wide and long, stresses his small scale, against the black emptiness of the space surrounding him. Ringing Bell demonstrates that if bad decisions can be made by children, then bad decisions can be made by the characters that children come to recognise. The moment of realism, the death of Chirin’s mother, for all its animated play, endures past the initial scene. It follows the canon of violence in children’s films in which the scene avoids being graphic by diverting the action from the camera, censoring the moment of predation. Instead, it offers a ‘zip ribbon’ graphic to show the moment the Wolf King kills Chirin’s mother, and maintains discretion by using a flurry of shadows on the barn wall.

Because of this, Chirin’s reaction is made all the more important. Instead of launching into song, or engaging in a heroic struggle with his morals, he renounces them, fearing death. Ringing Bell generates questions about the struggle to know the animal in relation to the ‘law of nature’, that prey must be eaten by predator. Additionally, Sanrio’s connection to character culture warns of the impermanence of youth in a metacommentary that attempts to stretch beyond the film, owing to its bright, animated format, that safety is not assured, spiritual, physical, or otherwise.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bordwell, David, Poetics of Cinema, (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2007)

Hata, Masami, dir., Ringing Bell (Crunchyroll, 1978)

Odell, Colin and Michelle Le Blanc, Anime, (Herts: Kamera Books, 2013)

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2008)

Wells, Paul, ”Stop Writing or Write Like a Rat’: Becoming Animal in Animated Literary Adaptations’, in Adaptation in Contemporary Culture: Textual Infidelities, ed. by Rachel Carroll (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), pp.96-197

Michi, ‘Chirin no Suzu’, (Tumblr post, @makyun, 21 January 2017)

Yanase, Takashi, Chirin no Suzu, (Tokyo: Froebel-Kan Co, 1978)

[1] Wells, Paul, ”Stop Writing or Write Like a Rat’: Becoming Animal in Animated Literary Adaptations’, in Adaptation in Contemporary Culture: Textual Infidelities, ed. by Rachel Carroll (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), pp.96-197 (p.96)

[2] Bordwell, David, Poetics of Cinema, (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2007) (p.15)

[3] Wells, Paul, ”Stop Writing or Write Like a Rat’: Becoming Animal in Animated Literary Adaptations’, in Adaptation in Contemporary Culture: Textual Infidelities, ed. by Rachel Carroll (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), pp.96-197 (p.98)

[4] Wells, Paul, ”Stop Writing or Write Like a Rat’: Becoming Animal in Animated Literary Adaptations’, in Adaptation in Contemporary Culture: Textual Infidelities, ed. by Rachel Carroll (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), pp.96-197 (pp.97 – 98)

[5] Wells, Paul, ”Stop Writing or Write Like a Rat’: Becoming Animal in Animated Literary Adaptations’, in Adaptation in Contemporary Culture: Textual Infidelities, ed. by Rachel Carroll (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), pp.96-197 (p.98)

[6] Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2008) (p.23)

[7] Wells, Paul, ”Stop Writing or Write Like a Rat’: Becoming Animal in Animated Literary Adaptations’, in Adaptation in Contemporary Culture: Textual Infidelities, ed. by Rachel Carroll (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009), pp.96-197 (p.105)

[8] Odell, Colin and Michelle Le Blanc, Anime, (Herts: Kamera Books, 2013) (p.13)

[FIGURES 3 – 4] Michi, ‘Chirin no Suzu’, (Tumblr post, @makyun, 21 January 2017)

[FIGURES 1 – 2, 5 – 24] Hata, Masami, dir., Ringing Bell (Crunchyroll, 1978)

FURTHER READING:

Patten, Fred, ‘”Ringing Bell” (1978) and “One Stormy Night” (2005)’, Cartoon Research, (2016) < https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/ringing-bell-1978-and-one-stormy-night-2005/ > [accessed 24 January 2023]

Toadette, ‘The Sanrio Films/Takashi Yanase Trilogy (1975-1978) – A Very, Very Special Cartoon Discussion of the Month!’, The Internet Animation Database (2016) < https://www.intanibase.com/forum/Posts/t2604-The-Sanrio-Films-Takashi-Yanase-Trilogy–1975-1978 > [accessed 22 January 2023]

Yano, Christine R., Pink Globalization: Hello Kitty’s Trek Across the Pacific (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013)

Sun, Vivian., ‘Bambi. Dir. David Hand. RKO Radio Pictures. 1942.’ (2018) shef.ac.uk<https://zooscope.group.shef.ac.uk/bambi/> [Accessed 20th January 2023]