Project X explores the journey of a chimpanzee named Virgil, taking him from the safety of his home with psychologist Teri Macdonald to an Air Force base where he participates in a secret experiment named Project X that trains chimps as pilots.

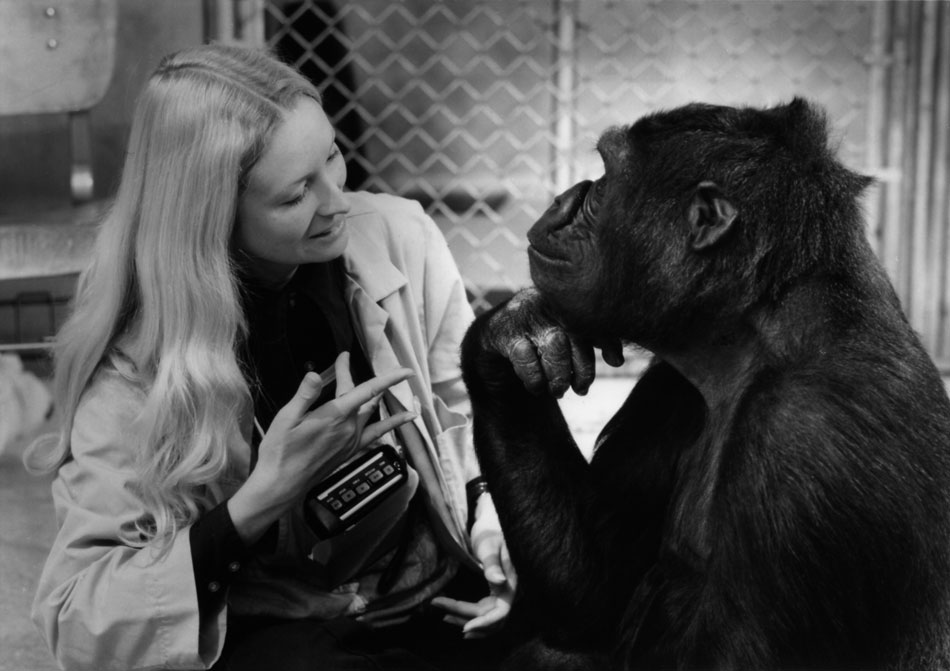

We learn that Teri has taught Virgil to communicate with humans via American Sign Language (ASL), which recalls Francine Patterson’s 1972 attempt to teach Koko the gorilla ASL.[1] Jimmy Garrett, new employee at the base, discovers that he can interact with Virgil through signing, and subsequently the two develop a close bond.

Teacher and Student: Patterson and Koko

Later, Jimmy learns that Project X fatally exposes the chimpanzees to radiation in order to discover how long human pilots could survive after a nuclear exchange. Once Jimmy realises that the chimps will die he enlists Teri’s assistance to rescue Virgil.

Meanwhile, Virgil has warned the chimps of their fate, but their initial escape plan is foiled by the military. Eventually, the chimps hijack a military plane, gaining freedom by crash landing into the Everglades and evading capture.

Project X embodies the science fiction genre by representing a fantastical world where futuristic technology has taught chimps to fly planes. The film portrays chimps operating technology as effectively as humans do in order to evoke the fear that animals could be smarter than we think, intimating that they could eventually surpass mankind and render us obsolete. This subverts generic conventions because most science fiction films use artificial intelligence to unsettle mankind’s claim to dominance on earth, whereas Project X uses chimpanzees in order to urge viewers to challenge animal exploitation.

Science fiction films are typically apprehensive about our misuse of technology, which is exemplified by Project X’s revelation that exploiting animals through technology for mankind’s gain will come back to haunt us. This happens when the chimps escape from the base in a military plane, an outcome that was made possible by the flight simulator that trained the chimps as capable pilots.

Science fiction estranges its audience from the reality that exists beyond the silver screen. Project X does this by estranging us from our assumption that humans are smarter than animals through depicting the chimps outsmarting the military. This is evident when the camera cuts from the chimps building a tower to enable their escape, to the control room where the military are floundering helplessly in their struggle to stop the chimps from running riot. This scene represents the ability of intelligent animals to undermine human authority, exemplifying Project X’s determination to estrange us from our reality by reversing the species hierarchy that elevates humans over animals.

Ultimately, I am interested in Project X’s use of human-animal relationships to demonstrate that human interference endangers animal welfare, an idea that I will return to throughout my article.

The film opens with an establishing shot of an Edenic landscape where wild animals co-exist harmoniously. Sadly, this peace does not last for long since the scene’s tranquil flute music is interrupted by a gun shot signifying the presence of a poacher threatening to destroy the harmony.

This establishing shot captures animals within their natural environment, imagining a pre-Fall world where animals are uncorrupted by mankind in order to argue that animals should be liberated from human interference. The danger that human interference poses to animals is represented by the poacher whose rifle threatens to devastate the animal community. The bang of this man-made weapon interrupts singing birds, who subsequently fall silent, in order to represent man’s determination to destroy nature through deforestation and poaching.

.

The film opens with a variety of wild animals such as elephants and giraffes frolicking in nature. Amongst these animals are chimpanzees, establishing the subject matter of the film.

Project X ends with an establishing shot of Virgil and his friends enjoying their freedom in the Everglades, mirroring the idyllic landscape in which the film began. The decision to bookend the film with images of animals in their natural environment reveals that Virgil’s journey has returned him to his true home in nature, leaving the viewer with the impression that animals are safer without human interference.

Virgil and his girlfriend in their new home at Floridian National Park, the Everglades.

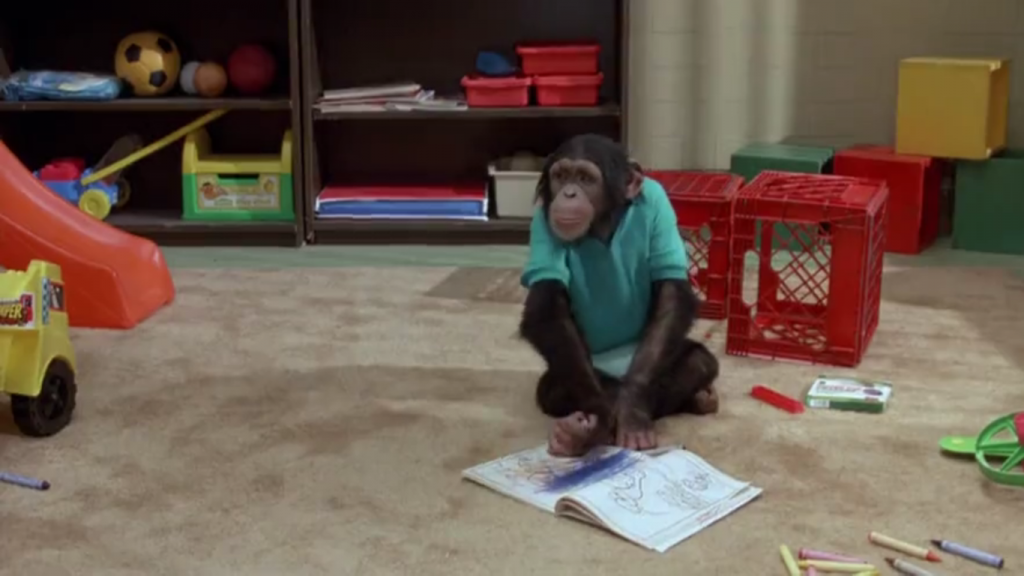

Virgil’s time with Teri has endangered his biological identity since her treatment of him as a human child encourages him to develop infantile behaviours, like playing with toys, that estrange him from his species. The camera employs a long shot that captures Virgil wearing clothes. Since humans are the only species to wear clothes, Virgil’s outfit demonstrates his ability to transgress the boundary between humans and animals as a human-animal hybrid. Virgil’s species hybridity implies that the human-animal boundary is not impenetrable, suggesting that we are not as distinct from animals as we would like to think.

Teri’s ownership of Virgil parodies the custom of pet-keeping to show that even people who treat animals compassionately can endanger them. Virgil is portrayed as a pet through the whimpering noises that he makes to attract Teri’s attention. These noises liken Virgil to a pet dog in order to demonstrate his dependence upon his owner’s indulgence of his needs, rendering him vulnerable if he were ever separated from her. This criticises humans who raise wild animals as domestic pets because this leaves the animals unable to fend for themselves in the wild.

The shot on the left depicts Virgil pouting like a petulant child, revealing that Teri has spoilt him.

On the right, the shot of the circus chimp puffing out smoke whilst gazing into the distance portrays him as more mature than Virgil. Essentially, it shows how circus life has corrupted his innocence by making him jaded.

Unfortunately, Teri is forced to give Virgil up when her funding is cut, meaning that Virgil must learn to cope on his own. Virgil’s vulnerability is revealed through a close-up of him clutching a toy crocodile which indicates his dependence upon a toy to comfort him in Teri’s absence. The camera cuts from Virgil and his toy to “an old circus chimp” smoking a cigar that employee Robertson gave him, juxtaposing the two chimps in order to contrast Virgil’s innocence with the circus chimp’s corruption. [1] This close-up of an animal smoking makes for a comical image that entertains the surrounding employees, which was Robertson’s intention when he provided the cigar. Fundamentally, this reveals that the chimp’s exploitation in the circus has reduced him to an object of human spectacle.

The props of cigar and toy demonstrate that human interference has estranged both chimps from their species by teaching them human behaviours. Teri’s nurturing of Virgil has resulted in his reliance on a child’s toy, while the corruption of the circus trade has developed a smoking habit in the circus chimp; both of which are unnatural behaviours for wild animals.

Clearly, human interference in animal lives is dangerous and exploitative, but what gives us the right to interfere with animals in the first place?

Essentially, we feel entitled to exert control over animals because we, as humans, have access to the spoken word while animals do not. Our unique claim to language gives us the power to name animals that cannot name themselves, and since this makes us ultimately responsible for moulding their identities, we use our ability to name animals as a claim to authority over them.

Each chimp in Project X is differentiated by a name chosen by the employees, indicating that the employees have constructed the chimps’ identities. In the employees’ eyes, this makes the chimps their property, which encourages them to grant themselves authority over the chimps. However, the employees exploit this authority, believing that it entitles them to endanger the chimps’ welfare by exposing them to radiation in an experiment that promotes mankind’s survival. This embodies the way that we endanger animals through animal testing that is for the gain of our species, but at the expense of others .

Jimmy demands to know what gives these employees the right to interfere with the chimps’ welfare, angrily asking his superior “who made you lord of the apes?” [2] “Lord” alludes to God’s supremacy, reminding us of his decision to grant Adam power over the animals by allowing him to name them. [3] Ultimately, our claim to authority over animals originates from God, which explains why the belief that we are superior to animals is so deeply ingrained in our culture.

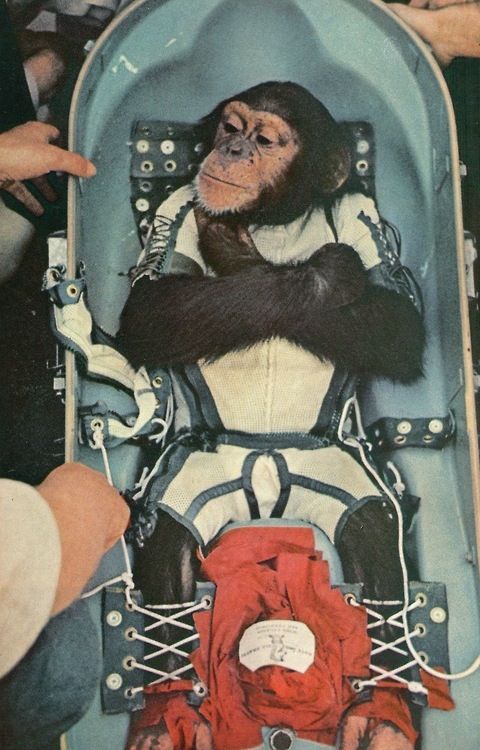

Going back to the chimps’ names, one is called Goofy, which is anthropomorphic since it alludes to foolishness, a characteristic not naturally located in animals. Ironically, humans tend not to allocate personal names to animals that they have effectively sentenced to death in, say, a slaughterhouse as it may cause them to become attached to the animal. By this logic, HAM, the chimp launched into space in 1961, was known only as no. 65 prior to his flight due to the possibility of a public outrage if he died with an anthropomorphic name. [4]

The objective decision to conceal HAM’s identity in order to avoid a scandal is reflected by the unemotional way that Bluebeard’s death is acknowledged by binning his name sticker. Both instances reveal that we neglect the identities of animals used in scientific research. The camera employs a static shot of the bin into which Bluebeard’s name is thrown, encouraging the viewer to contemplate the way that the chimps’ identities are discarded because they are defined only by their value to human knowledge. Once they die they are of no further use, and so they are forgotten immediately. Contrast this with the years that some people mourn a pet’s death and it becomes clear that we invest more value in a pet than in a group of research animals that have no meaning to us outside of their scientific function.

This shot reinforces the unemotional way in which we disregard the deaths of research animals since, moments after Bluebeard’s death, this employee is cleaning out his cage ready for its next inhabitant.

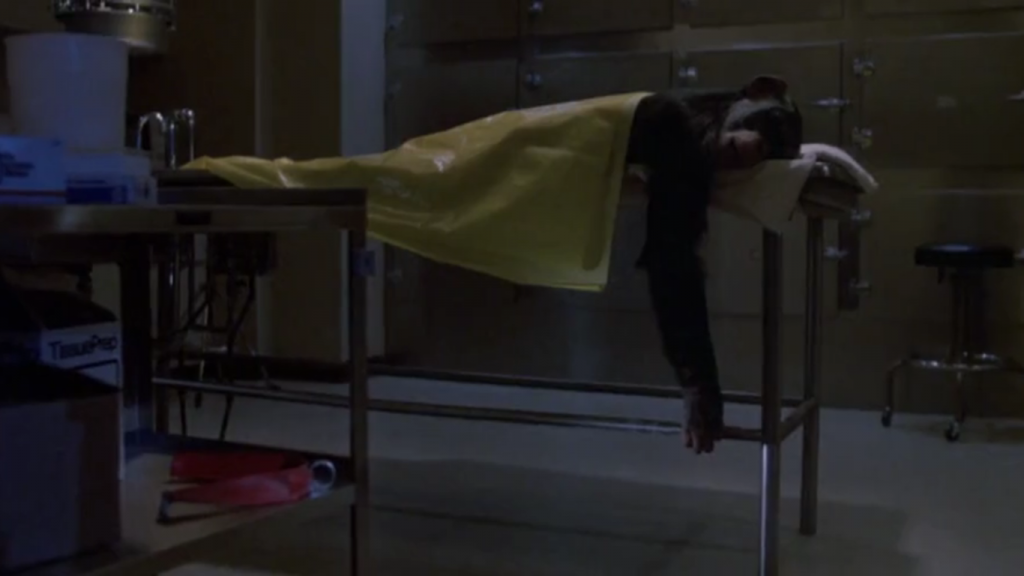

Bluebeard’s corpse is shown to us through the camera’s low angle and shaky motion that indicate we are observing the dead chimp through Virgil’s perspective. This point-of-view shot helps us empathise with Virgil’s pain, zooming into his forlorn expression to reveal that he has been scarred by the military’s neglect for animal lives.

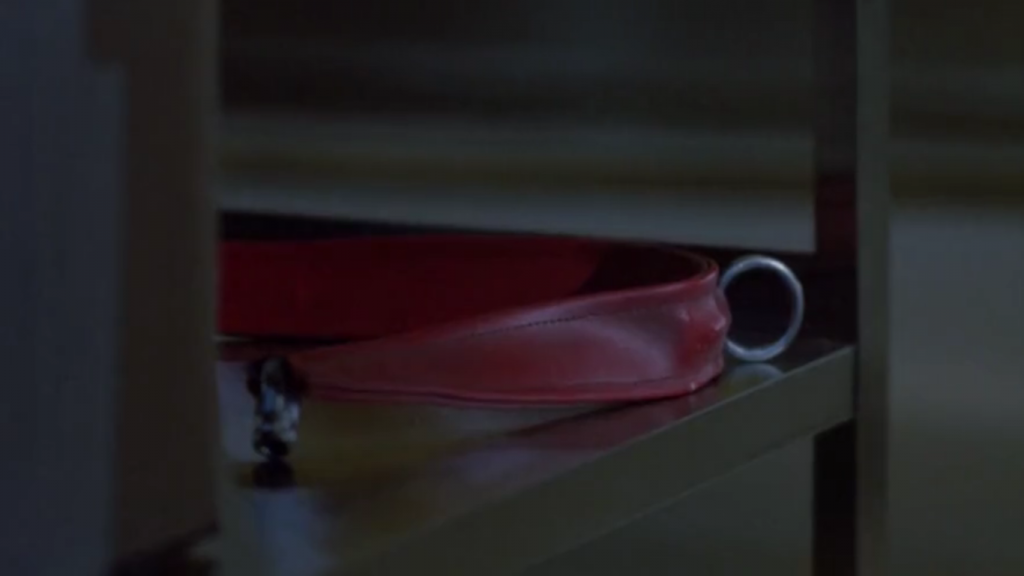

From Virgil’s perspective, the camera cuts from Bluebeard to the red collar that is put on chimps who have graduated from the programme, and are thus ready to be exposed to radiation. This shot transition represents animals’ ability to reason, showing Virgil making a logical connection between Bluebeard’s death and the collar as he learns that the project culminates in the chimps’ deaths. Virgil’s realisation that he will die soon reveals that Project X has corrupted his innocence by giving him a preternatural awareness of his mortality.

First, Virgil sees Bluebeard’s corpse. His dead hand hanging carelessly off the edge of the gurney shows how little care the Project X employees have for animals even in death. Next, the camera cuts to this red collar, revealing that Virgil has automatically noticed a connection between it and Bluebeard’s death.

Project X intends us to sympathise with Virgil by making him a likable and vulnerable character. The aim of this is to encourage us to react with rage when we learn that he and the other chimps are being raised for the slaughter. The film fundamentally expresses an animal rights message that urges us to condemn all forms of animal murder, including the very real slaughter of animals for meat, as wholeheartedly as we condemn the deaths of anthropomorphised animals in a dramatized Hollywood film. The film uses chimpanzees to convey this message because primates are the closest species to humans, and with this in mind, we are more likely to sympathise with chimps than we would with any other animal. Consequently, our intimate connection with the chimps makes it all the more likely that the film will change our attitudes towards animal murder.

Secondly, Project X demonstrates that human exploitation of animals is not always cruel and calculated, and that sometimes we can inadvertently mistreat animals despite our good intentions. In this sense, Teri’s mollycoddling treatment of Virgil as a pet exemplifies the way in which we can, in a manner of speaking, kill animals with kindness. Teri’s devoted attention to Virgil and her indulgence of his every need may be well-intentioned but it results in his unnatural dependence upon human support, leaving him unable to cope alone when he is separated from Teri at the military base. Virgil’s vulnerability is further demonstrated through his close attachment with Jimmy, the first human that he meets at the base, whose arms he immediately leaps into. This reveals the potential for Virgil’s safety to be jeopardised by his overly trusting nature since Project X reveals that not all humans are equally concerned about animal welfare.

My analysis of Project X reveals that it aims to criticise the human exploitation of animals; be it their use in dangerous military experiments, or the degradation of wild animals to pets or circus freaks. Ultimately, Project X shows that human authority over animals endangers animal welfare through the pet ownership that makes Virgil so vulnerable; the circus industry that reduces chimps to caricatures, and the military experiment that murders chimps. Being influenced by the science fiction genre, Project X naturally lends itself to comparison with the 1968 Planet of the Apes. Both films subvert the species hierarchy that elevates humans over animals since Planet of the Apes constructs a world where apes are superior to humans; while Project X shows the chimpanzees outwitting the clownish military at every turn, and ultimately triumphing over them by escaping from the base.

[1] Donna Haraway, Primate Visions : Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989), p. 141

[1] Haraway, Primate Visions, p. 138

[2] Project X. Dir. Jonathan Kaplan. 20th Century Fox. 1987

[3] Project X. 1987

[4] Project X. 1987

Suggestions for further reading:

Haraway, Donna, Primate Visions : Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989)

Hearne, Vicki, Adam’s Task: Calling Animals by Name (New York: Knopf, 1986)

Bibliography

Haraway, Donna, Primate Visions : Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989)

Project X. Dir. Jonathan Kaplan. 20th Century Fox. 1987