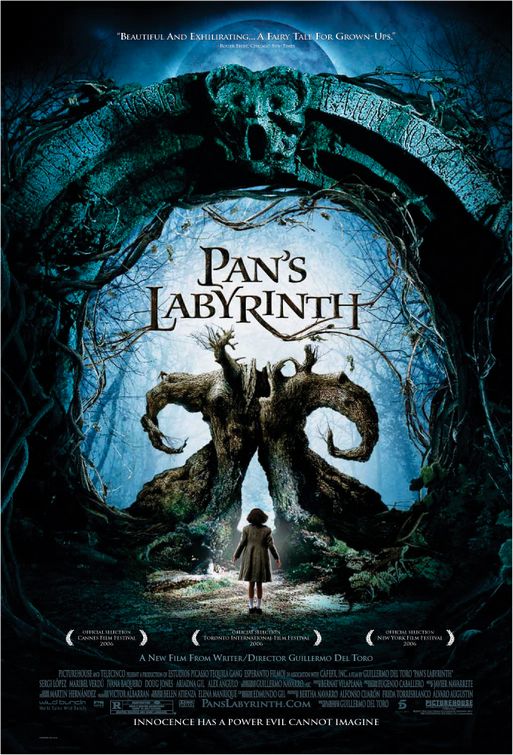

Pan’s Labyrinth (Original Title: El laberinto del fauno)

Guillermo del Toro’s visually arresting Pan’s Labyrinth is set in 1944 against the backdrop of post civil-war Spain. It follows the story of the young Ofelia, whose heavily pregnant mother has transported her across the country to live with her fascist stepfather, Captain Vidal, as he carries out Franco’s orders to quell enduring resistance to the regime. Once there, and faced with the bleak reality of life under her mother’s authoritarian husband, Ofelia discovers an enigmatic faun dwelling at the centre of a mysterious labyrinth. The creature informs her that she is in fact the long-lost princess Moanna of an underworld kingdom for whom he has been lying in wait, hoping to guide her back to her rightful home. However, she must first complete a series of tasks to prove that her soul is yet uncorrupted by the human world. Subsequently, Ofelia’s narrative is split between the dismal world of Francoist Spain that sees animals used with indifferent utilitarianism for the upkeep of the community, and a parallel fairytale world in which she encounters a range of fantastical creatures that shape her fate. By the conclusion of the film, the two worlds have seeped into one another, leaving the viewer uncertain as to the implications of Ofelia’s tragic death at the hands of Vidal.

Del Toro’s internationally acclaimed masterpiece adheres to motifs and themes of war film, horror, and fairytale, hybridising the three genres, but as Jennifer Orme notes, it refuses to ‘ satisfy […] conventional generic expectations’[i] of any one. Falling initially within the bracket of war genre, the film calls into question the morality of the senseless killing and brutality of Franco’s regime, embodied in the character of the bellicose Vidal. To effectively articulate the callous barbarity experienced by Spain’s people, del Toro looks to the genre of horror to supply an excess of extravagantly gory violence. The film ultimately turns to the tropes and motifs of fairytale as a vehicle for its message. It is here that animal presences feature most notably, in the form of del Toro’s nightmarish creations; forces of ambiguous morality that Ofelia must navigate. The fantastical realm of the underworld kingdom conjures forth fairy guides, a grotesque toad that resides at the base of a fig tree, a monstrous figure dubbed the Pale Man, a mandrake root, and of course, the titular faun. Where Vidal’s realist world presents animals as passive tools, the fantastical equivalent privileges creatures of autonomous agency. Indeed, animals in the ‘real’ world of the film appear as visual components, rarely the focus of the shot, in dull surroundings that draw little or no attention to their presence. In stark contrast to this, the fantasy creatures are visually emphasised with a colour palette of warm amber tones and placed firmly in command of the shots they feature in. The filmoperates around a central theme of obedience and disobedience[ii] intrinsic to the moral teachings of many fairytales. As Orme observes, it is the very same disobedience that bleeds in to the generic structure, denying the audience the satisfaction of adherence to a set of rules.[iii] The animals within the film’s realist sphere, being deprived of agency, do not support this. However, looking to the fairytale creatures, there are multiple instances of generic transgression that they reinforce; not least the faun’s repeated appearance in Vidal’s world, a domain he has no business frequenting.

The two narrative spheres of the film engage animal presence in entirely different ways, although primarily both use animals to examine the morality of humankind. Captain Vidal is a man transfixed by controlling his environment to the point of obsession, a trait that creeps into every aspect of his character, from his meticulously kept appearance to the rigid structure of his torture tactics. He is the overriding dictatorial presence, as del Toro aptly remarks, he devoutly adheres to fascism and the ‘institutional lack of choice’[iv] that it represents. It is therefore fitting that the animals operating within his world are deprived of autonomous action.

Indeed, the first definitively real animals we see are two young rabbits, killed by the town’s folk to supplement their pitiful ration allowance. On a literal level, the rabbits’ presence provides contextual information about the living conditions of Spanish citizens. On a figurative level, however, the rabbits embody the extreme passivity demanded by fascist figures; their will is so unimportant that they are of equal value when robbed of any capacity to act within their own right. This is represented in the film by introducing them via discussion rather than visually. As a consequence, their initial presence is weak in that it is only verbal. When they finally do appear on screen, they are relegated to the edge, out of focus, and present only fleetingly. In this way the cinematography reflects their passivity. Their presence in the film also carries the implication that Vidal’s activity goes against nature; he is stationed in the heart of a forest, intruding upon the rabbit’s native habitat, and yet, the influence he exerts results in the death of these animals.

Another animal whose presence features in the ‘real’ narrative is that of the horse. Horses in Pan’s Labyrinth appear in the passivity of a herd, deprived of individual character development and used for the benefit of the fascist militants. Their presence is unremarkable, and intentionally so; they are never in the frame without their human overseers, and the audience is never given any information from their perspective. In Vidal’s world, and to the logic that inhabits it, animals are merely tools. Indeed, they are very rarely captured in the shot in their entirety. They appear only marginally, framing the human riders who deprive them of agency. Their capacity to choose is removed as they too are forced into a passive obedience.

In stark contrast to this stands the active presence of the creatures in Ofelia’s fairytale world. In an interview with the British Film Institute, del Toro asserts that he ‘wanted to represent political power within the creatures’[v]. In order for this to be plausible, they operate within an environment that attributes narrative attention and power to them.

The first fantastical creature we encounter as viewers is the insect/fairy, who appears within the establishing scene of the film. During a halt on the opening journey to Vidal’s stronghold, Ofelia finds a stone engraved with the image of an eye, which she returns to its rightful place in the face carved on a monolith by the edge of the road. Instantaneously, a praying-mantis-type insect vivaciously pops out of the monolith’s mouth in a close up shot that centralises focus on it. Subsequently, the camera follows the insect as it observes Ofelia’s return to the cars and her journey towards her new home, literally looking over its shoulder in a gesture that attributes influence and purpose to the creature. Later, and in the same cinematic style, it is the insect that leads Ofelia to the labyrinth for the first time. Unlike the horses, this creature is given narrative agency. Furthermore, the heroic protagonist Ofelia also gives it her attention. Since our loyalties are aligned with Ofelia, we can deduce that her willingness to heed the guidance of even the smallest of creatures is esteemed as an admirable attribute.

Enshrined in the title, the faun is perhaps the most important mythical creature in the film. Vaguely unnerving in appearance, he seems to be hewn from the very wood of the forest he inhabits. This, as del Toro notes, is a product of expert character design[vi]; classically speaking, fauns are morally ambiguous figures that personify nature[vii], so for del Toro, it was vital that the faun should visually represent this. His moral ambiguity is reiterated throughout the film, as we see him oscillate between comforting and chastising Ofelia. If he does not provide a safe retreat from the bitter reality of Ofelia’s life, what then is his purpose in the film? Fundamentally, he is the source of Ofelia’s trials; the set tasks that require her to act obey or disobey established rules. True, forces of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ exist, although as Ofelia discovers, it is only through the power of choice (one that does not consistently adhere to the moral binary) that one can truly fulfil one’s potential.

Clearly then, the presence of animals in the film is important on two levels; initially, the level of attention granted to creatures, be they real or fantastical, is an indication of a character’s morality. However, in their physical embodiment of nature, they enable a deeper examination of an entity’s worth, one that transcends the moral binary. In the face of fascist dogma, the film privileges an individual’s capacity to choose, that is, to obey or disobey established rules according to one’s inner essence. The presence of fantastical creatures is vital to achieve this, as they bring forth a natural environment in which this can happen. However, they do not solely conjure an environment in which choice can take place, they also function as agents of plot progression, provoking characters into acting. In an environment where passivity is expected in the face of fascism, the fantastical creatures are key in dissolving Ofelia’s hesitation to act. Where the ‘real’ human world is corrupt and twisted, the fantasy world inhabits a more neutral, natural space necessary for true choice, and provides occasion for the characters to do so.

Pan’s Labyrinth is thematically remarkably similar to Ken Loach’s Kes. In both films, animal presence is used as an escape for a young protagonist whose reality is too bleak to face. For them, animals come to symbolise alternative possibilities, either in the form of betterment or liberation. Where Loach explores this through social realism, del Toro uses magical realism. Notably, animals cannot be classified as pets in either film; the possibilities they embody warrant greater respect than a relationship that operates on a binary of owner and owned. Furthermore, the animals in both Kes and Pan’s Labyrinth encourage transgression on the part of the protagonist; Billy must steal the bird in order to engage with it, and Ofelia must disobey the orders of her human guardians to complete the tasks set to her by the faun.

[i]Jennifer Orme, ‘Narrative Desire and Disobedience in “Pan’s Labyrinth”’, Marvels & Tales, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010), <https://www.jstor.org/stable/41388953> [accessed 12/11/14], pp.219-234 p.219

[ii]Director’s commentary, Pan’s Labyrinth, Dir. Guillermo del Toro. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2006.

[iii]Jennifer Orme, ‘Narrative Desire and Disobedience in “Pan’s Labyrinth”’, Marvels & Tales, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010), <https://www.jstor.org/stable/41388953> [accessed 12/11/14], pp.219-234 p.219

[iv]Author not specified, ‘Girl Interrupted’, BFI, https://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/49337, (accessed 12 November 2014)

[v]‘Girl Interrupted’, BFI.

[vi]‘The Power of the Myth’, DVD extras, Pan’s Labyrinth, Dir. Guillermo del Toro. Warner Bros. Pictures, 2006.

[vii]‘Fauns and Satyrs’, TV tropes, https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/FaunsAndSatyrs (accessed 12 November 2014)

Suggestions for further reading:

Kotecki, Kristine, ‘Approximating the Hypertextual, Replicating the Metafictional: Textual and Sociopolitical Authority in Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth’

Marvels & Tales, (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010) Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 235-254, 192, 369.

Smith, Paul Julian, ‘Pan’s Labyrinth (El laberinto del fauno)’, Film Quarterly, (Berkeley: The University of California press, 2007). Vol 60, No. 4, pp. 4-9.

Ebert, Roger, Pan’s Labyrinth, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-pans-labyrinth-2006

Film: Pan’s Labyrinth, TV Tropes, https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Film/PansLabyrinth

Bibliography:

Del Toro, Guillermo, Pan’s Labyrinth, Warner Bros. Pictures, 2006.

Orme, Jennifer, ‘Narrative Desire and Disobedience in “Pan’s Labyrinth”’, Marvels & Tales, Vol. 24, No. 2, (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010), <https://www.jstor.org/stable/41388953> [accessed 12/11/14], pp.219-234

Author not specified, ‘Girl Interrupted’, BFI, https://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/49337, [accessed 12 November 2014]

‘Fauns and Satyrs’, TV tropes, https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/FaunsAndSatyrs [accessed 12 November 2014]