“It’s not destroying. It’s creating something new”.

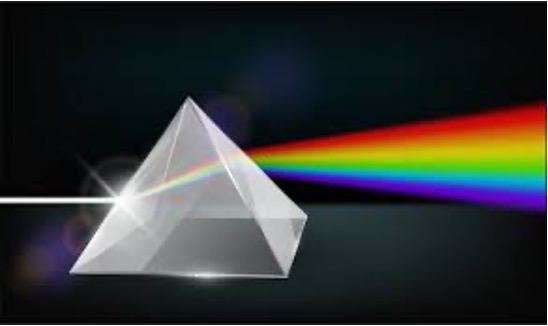

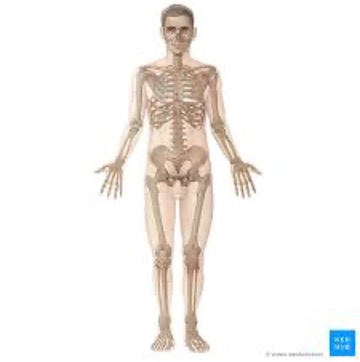

Annihilation, by definition, is something “Completely destroyed; nothingness, non-existence”, Yet Alex Garland’s 2018 film entirely rethinks what it really means to be obliterated. Annihilation follows the perilous journey of Lena (Natalie Portman) and four other female scientists into a mysterious, expanding biome named ‘The Shimmer’, as an attempt to discover its source. This phenomenon is a scientific mystery, creating multiple inexplainable circumstances such as all five women losing their memory of their first three days inside, and all the radio signals becoming distorted despite the satellites being right above them. As their mission continues, they encounter multiple horrifically altered and mutated animals, including an albino alligator with shark’s teeth, a huge worm-like parasite, and a decaying bear which morphs with its victims. It eventually becomes clear that ‘The Shimmer’ is a prism, refracting the radio signals, and more shockingly, all DNA – plant, animal, and even human DNA, threatening what it means to be human or animal.

These mysterious changes and mutations created within ‘The Shimmer’ place this film into a rare subgenre of horror which deals with the unknown, the incomprehensible and the (in)significance of human existence: cosmic horror. This genre is extremely psychological, forcing the viewer to ask questions about their own life and purpose. Annihilation therefore not only focuses on what it is that makes us human but also epitomising the disparity been life and death – Garland explores the unavoidable, terrifying inevitability of death and inexistence, but also pairs this fear with the beauty of life, represented in the sublimity of ‘The Shimmer’. The human-animal relationship illustrates this exploration of life and death with a hunter/hunted narrative, where the humans are constantly persecuted by the imminence of death in the form of these deadly animals. This focus on death evolves into an underlying tone of destruction – a physical, bodily destruction echoing the human destruction of nature and animals. Yet, this theme of annihilation is also mirrored by a disturbing creation of life. These animals not only take lives, but they also represent a creation of life, creating a unique contortion between the moment of life and death.

ALLIGATOR

The first scene in which the scientists encounter a mutated animal is, aesthetically, one of the most beautiful and relaxing scenes of the entire movie. There are birds chirping in the background, and the house they find is covered in flowers as if decorated for a wedding. The mise en scene therefore enhances the idea of sublimity and new creation, stemming from Lena’s discovery that multiple different species of plant are impossibly growing from the same branch. This serenity of scene removes any tension, allowing the alligator to emerge as a ‘jump-scare’, initially snatching Josie (Tessa Thompson) and dragging her into the murky depths without revealing itself. This horrifying scene casts back to the cosmic unknown – the fear of the unexplored, what is lurking below the surface? The alligator itself, much like the flowers is multiple species merged into one: it has rows of shark teeth and albino scales. Whilst the mutation of the flowers represents beauty and life, the alligator represents death, being evolved and designed to have the most effective kill.

Even after the alligator is shot dead by Lena, its association with death and destruction only becomes clearer. According to Katerina Gregersdotter, POV shots from the animal’s eyes are often used in horror cinema because “the POV shot not only lets the viewer see through the eyes of the animal but utilises the audience’s ability and (un)conscious attempts to make sense of and interpret what is shown on screen to represent the animal’s consciousness.” The first shot following the alligator’s death is therefore highly significant, as although there Isn’t a direct view from an eye, the point of view comes from inside the animal’s mouth. The scientists are framed within the alligator’s massive jaws and deadly shark teeth, creating the implication that even after death, this animal’s only motivation is to kill – it only looks through their jaws to ensure that a human is on the receiving end of them.

Not only does the alligator physically attempt to cause death, but it is also a figure of death itself. Whilst the albino scales represent a mutation, the lack of colour has connotations of a lack of life, as if all the energy and existence has been drained out of this animal, rendering it as an entirely cold and soulless being even before its eventual death. This soulnessness is also not only contained within the alligator. Throughout this film, there is a sense of mirroring between human and animal, and in this moment the viewer sees the soulnessness of humanity reflected in this animal. Lena is ex-military, allowing her to shoot the alligator dead with little hesitation- she is a trained murderer. Although it may seem as if she is defending herself, the image of Lena and the Alligator head on, both desperately attempting to kill the other creates a perfect mirror: there is no heroism, no saviour complex, it is a mutual hunting and, in each case, the only result is death, implying that the boundaries between human and animal are already becoming twisted.

WORM

Whilst the alligator was hidden by the idyllic scenery, the next animal encountered by humans in this film is similarly hidden, yet instead of eventually revealing itself it is a purposeful challenge to uncover. The staging of its discovery is extremely detailed and convoluted: there is a room, inside the room there is a bag, inside the bag there is a film camera, on the camera there is a video, in the video there is a man, and inside the man hides the creature. This parasitic creature is clever and thoughtful; a hunter playing the slow game, slowly feeding from this human on the inside and causing an equally slow and painful death. From Lena’s perspective, it is “a worm”, some kind of living parasitic creature resembling a huge tapeworm that has buried into this man’s body and is removing his life, again being a representative of death and destruction.

Figure 7 – Tapeworm

.

This parasite is however somewhat ambiguous. Despite causing this man to die, this ‘worm’ may also represent a new life. After witnessing the horrific video, Josie doesn’t refer to it as an animal, instead saying that “his insides were moving”, indicating that this creature didn’t infect him, but instead was produced from or grown inside his body. From this perspective, ‘The Shimmer’ has caused this man’s insides to mutate, becoming alive as an independent being to the body. Therefore, this ‘animal’ not only represents destruction, but human self-destruction.

“The organs, having rebelled against their appointed biological roles in the body, proceed along their own independent lines of being, thereby dooming the body to its death”.

His intestines have been altered to such an extent that they have become their own self, an animal that is both made up of the human body but still separate from it. Human has become animal in the most grotesque way. This bodily transformation, however, does not only represent self-destruction, as a new form of life has been created. The worm is a metaphor for both life and death, causing death in order to sustain its own new life. Humanity has become prey to a being of its own creation, creating a sense of revenge through nature and the natural world – whilst humans have destroyed nature and animals for their own gain, these animals are finally taking the lives of humans to build their own. This idea of selfish, life stealing growth is also a twisted analogy for pregnancy and childbirth. Whilst an embryo takes part of its mother in order to grow and become its own life, this new creation is still human, allowing humanity to thrive and grow. In Annihilation, the fact that it is a human man with a creature growing inside his stomach highlights how the laws of nature and life and death have been completely upturned, with the cutting of his stomach even somewhat representing a c-section. ‘The Shimmer’ has taken the ‘miracle’ of birth and demonised it. This creature creates a warped perception of life and death – not all life is good, and destruction or annihilation may be an outcome of this life.

.

.

.

BEAR

Despite this horrific imagery and blurring of human and animal, the worm is not the most terrifying animal depiction in this film.

Garland has taken a grizzly bear, already one of the most dangerous predators on the planet and made it even scarier – not by fusing it with an equally scary animal but with something even worse – humanity itself.

In ‘The Shimmer’, not only does human become animal, but animal becomes human.

Unlike the other animals, the bear appears twice, hunting the humans down as an incessant predator: he is the final challenge of nature. The first bear attack is at night and the entire shot is encompassed in darkness. The viewer is only allowed the same miniscule vision through a beam of torchlight as the scientists on screen, creating a terrifying moment where we are immersed in the danger and unknown. The first indication of the strength of this beast is when the metal fence gets torn in half “like a zipper”. To the scientists, this fence was a safety net, keeping the dangers of ‘The Shimmer’ on the outside of their bubble. Death awaits on the outside, and the fence is their insurance for life. As the bear crashes through the fence, this safety is removed and death enters life – the bear snatches Cassie (Tuva Novotny) and pulls her into the deadly forest, leaving the viewer with the sounds of her blood curling screams.

It is only at the bear’s second appearance, that we can get a grasp on it’s true nature. The first noise that can be heard as the bear approaches is a haunting repeat of Cassie’s final screams in the moments before her death. The bear is not only an inflictor of death, but it also merges with life, morphing with parts of Cassie’s consciousness as she died, taking on her screams. The bear is a creature who is both living and dead, trapping the living souls of its victims as a haunting reminder to all who follow. As the bear enters the rooms and begins to sniff around the tied-up scientists who can do nothing but remain silent, the tension is already breath-taking. This horror is only increased as the camera pans towards his fleshless face, where we get a glimpse of a set of human teeth behind its canines, and, even more horrifically, there is a human skull fused to the bear’s head. Through death, the bear not only metaphorically but also physically merges with his victims. It has become anthropomorphised in the most literal way, with a human voice and features. Alongside these features, much of the bear’s fur and flesh has completely rotted away, leaving raw bone underneath, as if its very nature is decaying. Life and death are converging, and nothing can escape it. The bear, typically a strong, powerful, undefeatable predator is becoming weakened by its merging with the humans. It is the human interference in this biome that is causing the bear’s pain, indicating that humanity has messed with the natural life and death of animals.

.

.

This film therefore creates an interesting relationship between humans and animals, largely focusing on the predator vs prey theme where the humans are constantly running from their deaths. The role reversal of humans being hunted highlights the irony of human destruction of animal life and they are made to face the repercussions of their own actions. This disparity between life and death also links to another human-animal relationship, that they are not as dissimilar as one might expect. Much like the alligator and Lena, we both kill, and our own life takes from others in the form of childbirth, much like the worm. Life and death conjoin humans and animals.

In Annihilation overall, Garland has created a critical reflection on what it means to live and die, suggesting that it is these two factors of life that link humanity to the animal world. Annihilation in this movie is not the destruction of humanity or animals, it is the destruction of preconceived ideas about the self – humans and animals collide despite being predator and prey, highlighting that the boundaries built up between both species must be broken down in order for the natural world to prosper.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

OED, ‘Annihilation, n., 1, www.oed.com/view/Entry/7897 [Accessed 17th January 2022].

Gregersdotter, Katarina, et al. Animal Horror Cinema: Genre, History and Criticism, (UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/sheffield/detail.action?docID=4082369.

Cheng-Hin Lim, Alvin, “Annihilation” and the Modes of Becoming, (2018), ippreview.com/index.php/Blog/single/id/674.html.

FURTHER READING

Ben Hadj, Emmanuelle, The (Im)Possibility of Adaptation in Alex Garland’s Annihilation,Period: Media and the Anthropocene, 2nd ed, (2021).

Gambin, Lee, Massacred by Mother Nature: Exploring the Natural Horror Film, Georgia: Bear Manor Media, 2012).

Newell, Jonathan. A Century of Weird Fiction, 1832-1937: Disgust, Metaphysics and the Aesthetics of Cosmic Horror. (Wales: University of Wales Press, 2020)